Acne is a multi-factorial disease. While each case is unique, you can greatly improve your chances of clear skin with food and lifestyle strategies.

What is acne?

Our skin is the largest organ in our body, and it’s a complex ecosystem made up of several layers and components.

The skin is semi-permeable, meaning that although it’s mostly a barrier between us and our environment, some stuff can get in and out. Sweat glands and hair follicles provide openings.

Hair originates in follicles deep in the subcutaneous layer, the deepest layer below the dermis. These hair follicles are paired with sebaceous glands, which secrete sebum, an oily substance that lubricates both hair and skin. (This is why your hair gets greasy if you don’t wash it.) Human sebum is primarily composed of triglycerides (40-60%), cerides (19-26%), squalene (11-15%), and small amounts of cholesterol.

We have hair follicles and sebaceous glands all over our body, except for the palms of our hands and soles of our feet.

Acne forms when pores become congested with old skin cells, which is more likely when the skin is oily and skin cells stick together. If we also have high levels of bacteria on the skin plus systemic inflammation, we have ourselves a full fledged acne party.

Acne vulgaris is the form of acne most of us are familiar with and accounts for nearly all acne experienced.

What contributes to acne?

Thus, anything that clogs pores, and/or creates or worsens infection and inflammation, contributes. The major players in acne production are:

- Excessive sebum (oil) production by the skin

- Rapid division of skin cells

- Delayed skin cell separation and death

- Bacteria on the skin surface

- Inflammatory response

The food we eat and our body fat cells play a role in sebum production, hormones, and inflammation. Hormonal changes likely have the greatest influence on acne (think birth control medications, anabolic steroids and puberty).

Hormonal factors

Growth hormone and IGF-1

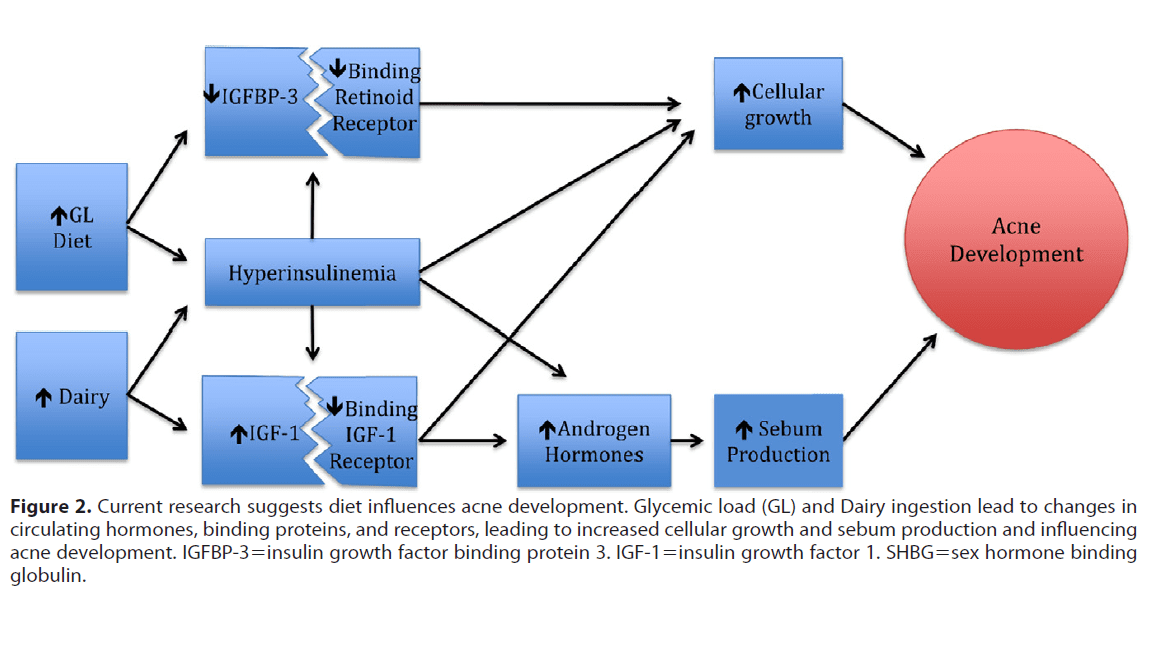

Acne during puberty is often associated more with growth hormone (GH) than with testosterone and estrogens. GH goes from the brain to the liver and triggers the release of Insulin Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1). IGF-1 promotes skin cell growth/division, sebum production, efficacy of luteinizing hormone (LH) and the production of estrogens.

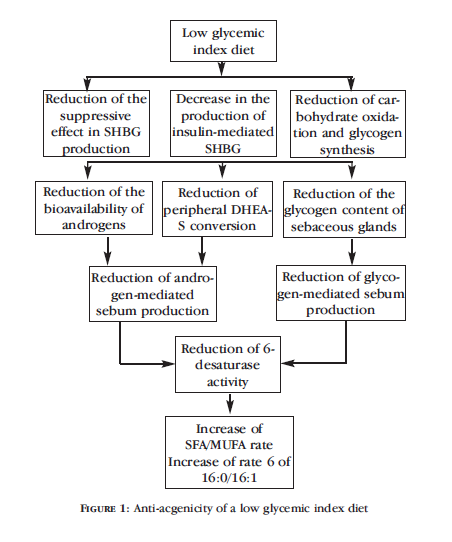

Insulin and glycemic response

A study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 1958 described acne as “diabetes of the skin.” And as far as I’m concerned, everything from the 1950s was true.

High insulin levels and insulin resistance are associated with worse acne and more sebum (side note: more body fat can lead to more insulin resistance). Medications that lower insulin and control glucose often have the side effect of less acne.

Androgens

Acne severity doesn’t seem to correlate with total androgen levels in the body. Rather, androgens play a permissive role in priming or initiating acne. An example of this would be women with PCOS or someone starting a cycle of anabolic/androgenic steroids. These folks often experience a surge of circulating androgens and IGF-1, along with lower levels of sex hormone binding proteins.

Androgens can directly influence skin cells if the cells have high levels of androgen receptors. Also, androgens can increase growth and productivity of sebaceous glands.

Consuming a lot of food promotes androgen release in the body. Animal foods and saturated fats tend to get the biggest response. Lower fat, higher fiber diets can increase levels of sex hormone binding proteins, thus lowering free levels of circulating androgens.

Inflammation & stress

Acne is a type of of inflammatory disease. With acne, inflammatory hormones and cell signals are upregulated — the skin is a hive of inflammatory activity.

Our bodies secrete cortisol in response to stress. Evidence shows that people with acne have an over-active cortisol secretion system, one that is particularly expressed in the sebaceous glands.

Thus, stress (whether physical or general life stress) plus inflammation (whether existing or prompted by stress) make acne worse.

Nutrition: What makes acne worse?

Not enough antioxidant vitamins and minerals

Low levels of vitamin C and E, zinc, selenium, and carotenoids might contribute to acne. These nutrients help fight free radicals that break down skin elastin, produce collagen, and repair skin damage. The catch here is that you usually have to get these from whole foods for them to be of any benefit.

Processed foods

Data show a mixed relationship between processed foods and acne. Eat a big meal with lots of processed food and you have lots of insulin. Lots of insulin means lots of tissue growth and androgen production, which are both contributors to acne.

Foods that are highly processed and cooked often contain compounds that promote oxidative stress and inflammation (see All About Cooking and Carcinogens). Again, oxidative stress and inflammation almost always contribute to chronic disease.

Dairy

While there have been noted associations between dairy consumption and acne starting back in the 1800s, some data indicate no association.

Milk provides a mix of growth factors, hormones and nutrients specific to offspring. As rapid growth ends and the youngster can feed themselves, milk consumption is stopped (well, not in humans).

Dairy foods produce a high insulin response, increase hormone levels in the body and alter inflammation – all factors that lead to unfavorable acne outcomes.

Consuming cow’s milk can raise IGF-1 levels 10-20% in the body. IGF-1 from cow’s milk survives pasteurization and homogenization and digestion in our gut, and can enter the body as an intact hormone (cow and human IGF-1 share the same sequence).

The unfavorable associations between dairy and acne haven’t been noticed with fermented dairy products, maybe because bacteria in fermented dairy use IGF-1, leaving less for us to absorb.

Some experts theorize that whey protein in particular may encourage acne, since it’s a strong promoter of insulin. A compound called betacellulin (which can be found in dairy foods) may increase skin cell division and decrease skin cell death – leading to worse acne.

Alcohol

Many studies link alcohol consumption to acne.

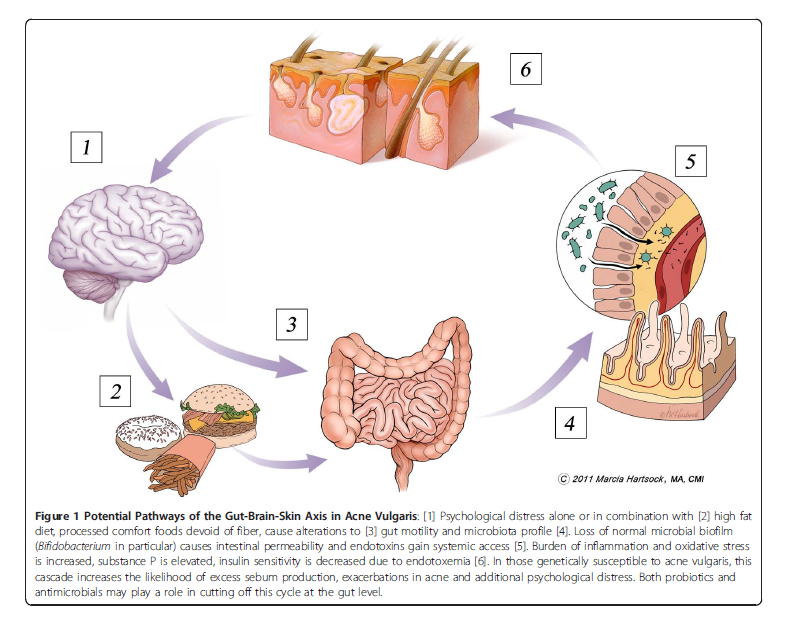

GI dysfunction & gluten

Acne is often correlated with GI tract dysfunction.

Those with acne might be more likely to experience gastrointestinal problems like bloating and constipation.

Gut health is often diminished when chronically stressed, leading to inflammation and maybe even a leaky gut.

There may be a connection between wheat gluten and acne (as well as between gluten and other skin conditions). Consider eliminating all sources of wheat and gluten from your diet for a month and see if that helps.

Nutrition: What makes acne better?

Acne is a big deal. While genetics (mom seems to play a bigger role) and ethnicity contribute to acne, it appears that how we live each day matters too.

In the U.S., people spend more than $100 million on over-the-counter products to fight acne. Yet many non-Westernized populations have no acne at all.

So, you could spend a lot of money on drugs that have potentially dangerous side effects… or you could change your diet. Changing your diet is a heckuva lot cheaper and safer as a starting point.

Whole plant foods

Diets based around whole plants can lead to slightly lower IGF-1 levels and slightly higher IGF-1 binding protein levels (leaving less available IGF-1 circulating in the body). This might help reduce acne.

Not Overeating

Less food coming into the body is associated with less sebum production.

Phytoestrogens

These substances, found in foods such as soy, may inhibit androgen-forming and acne-promoting enzymes, but don’t appear to play a major role in helping acne.

Cocoa

There doesn’t seem to be an association between chocolate (in its most unprocessed form) and acne. Studies show that dark chocolate can improve insulin sensitivity and improve blood flow to the skin and skin hydration. (Some manufacturers are even capitalizing on these studies by offering chocolate in skin products. The jury’s still out on whether this works, but it sure makes you smell tasty.)

Omega-3 fats

Skin levels of fatty acids might play a role in the development of acne. Furthermore, the pro-inflammatory Western diet (with lots of omega-6 fats) tends to negatively influence acne. Balancing fat intake and ensuring enough omega-3s seems to be important for overall skin health. 1 gram of EPA from a supplement (check your fish oil to see how much EPA is in it) might be useful for acne treatment.

GI health

As mentioned above, poor GI health is strongly correlated with acne. Whole foods, soluble and insoluble fibre, omega-3 fats, coconut, and Brassica vegetables (cauliflower, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, kohlrabi, etc.) can have a beneficial influence on gut health, in part by improving gut motility. (See diagram below.) Fibre can also bind to and excrete excess hormones that contribute to acne.

Consider eliminating wheat, dairy, and sugar for a month to see if this helps. All of these things worsen GI tract problems, and acne is strongly connected to gluten enteropathy.

Pre/Probiotics

This might be of particular interest to anyone who has been using antibiotics for acne. Our gut is home to countless bacteria and if gut health is out of whack, this might have a negative influence on acne. Getting enough of these from foods and/or supplements can help to restore gut health and may reduce acne.

Skin cells have also been found to act as immune cells that signal an over-active immune system. Inflamed skin means inflamed body, and probably inflamed gut.

Spices

Many spices (e.g.cinnamon, ginger, turmeric) and fresh herbs (e.g. basil, oregano, garlic) are anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, and immune-boosting. Spices such as cinnamon can also help to regulate insulin.

Green tea

Green tea can suppress enzymes and androgens involved in acne formation. It’s also anti-inflammatory.

Walnuts/almonds

These nuts might help with blood/skin fatty acid status, and control blood sugar. Monounsaturated fats can be anti-microbial.

Dark green & purple vegetables/fruits

These contain acne fighting anti-oxidants and minerals that extinguish inflammation. They may also inhibit androgen-forming and acne-promoting enzymes.

Free-range organic (or pastured) eggs

Hens that receive nutritious feed (or even better, free-ranging pasture that includes bugs and other small animals) produce more nutrient-dense eggs (including beneficial vitamin A and omega-3 fatty acids) that may help to deter acne.

Tomatoes

These may lower IGF-1 in the body.

Resveratrol

Found in grapes, red wine, peanuts and mulberries.

Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid)

Supplementation with pantothenic acid (500-1000 mg daily should be sufficient) can be quite effective, and a far safer alternative to commercial prescription medications such as oral contraceptives and retinoids.

Zinc & selenium

6% of all zinc found in our bodies is in our skin. Selenium is a potent antioxidant. It’s best to get these in food format.

High-zinc foods include seafood, wild game, red meat, nuts, seeds, and mushrooms. High-selenium foods include nuts (Brazil nuts in particular), fish, poultry, meat, wild game, mushrooms, whole grains, and eggs.

Who doesn’t get acne?

Observing cultural shifts in diet can also clue us into what foods might be associated with acne.

Acne doesn’t seem to appear in non-Westernized populations eating traditional diets. This includes Inuit, Okinawa islanders, Ache hunter-gatherers, Kitavan islanders, and rural villages in Kenya, Zambia and Bantu.

Staple foods among cultures where acne is nearly absent include:

- tubers (e.g. taro, yam)

- fruit

- fish, seafood, and marine mammals

- coconut

- vegetables

- wild game

- groundnuts and tree nuts

- traditionally prepared (fermented or ash-treated) non-wheat grains such as millet, barley, maize (corn), or rice

- beneficial fungi, molds, and lichen

They don’t eat processed foods, sugars, flours or processed wheat, processed oils, nor much dairy. They also get plenty of vitamin D from being outside, and/or consuming the livers of marine animals.

Summary and recommendations

Acne is complex, and each person is unique. However, there are common factors in cultures that don’t suffer from acne. Use these ideas as your starting point and our recommendations.

- They eat whole, unprocessed foods. All their nutrients come from these foods. They don’t supplement.

- They get outside and get sunlight (or, again, consume vitamin D in organ meats).

- They often eat fermented foods — foods that are high in beneficial probiotics for gut health.

- Except for the Inuit, they eat a lot of unprocessed and/or traditionally prepared plant foods, such as fresh or fermented vegetables and fruits, and grains that are soaked/sprouted/fermented.

- They often eat many fresh herbs and spices, as well as beneficial fungi.

- They eat a good balance of unprocessed fats.

- They eat plenty of omega-3 fatty acids from fish, wild game, and even insects and snails. They don’t consume a lot of omega-6s from vegetable or seed oils.

- They eat traditionally prepared ground nuts (e.g. peanuts) and tree nuts (e.g. walnuts, almonds).

- They don’t consume much dairy; if they do, it’s fermented and/or pastured.

- They eat as much as possible of any animals consumed: dark and white meat, organ meats, connective tissues, etc.

The value of self-experimentation

If you struggle with acne, keep a food diary. Look for connections between foods and breakouts — and don’t forget that it might take a day or more for foods to stimulate breakouts.

One good experiment is to try doing without wheat, dairy, and sugar for a month to see if it helps. These foods have the strongest associations with acne. Substitute tubers, fruit, and beans/legumes for carbohydrate instead. If that seems like too much, try just one thing at a time.

Other factoids

During times of hormonal fluctuation (like puberty) excess sebum production likely occurs to protect hair follicle growth.

Our skin is replaced every 28 to 45 days. Sebaceous glands have receptors for neuropeptides, like endorphins.

Histamines and anti-histamines may influence sebaceous gland function.

Environmental pollutants

Environmental pollutants might bump up IGF-1 levels. Pollution — which includes smoking — also increases oxidation. Smoking can also influence acetylcholine, and acetylcholine can influence sebaceous gland activity.

Natural topical treatments

The plant extracts from Azadirachta indica (Neem), Sphaeranthus indicus (Hindi), Hemidesmus indicus (Sarsaparilla), Rubia cordifolia (Common Madder) and Curcuma longa (Turmeric) seem to be anti-inflammatory and might suppress bacteria on the skin that promote acne. Same with topical tea tree oil.

If you’re looking for a cheap vitamin A cream, try egg yolk. Dab it on your skin and leave it for 10 minutes or even overnight. (Just remember to wash it off eventually.)

Chamomile and peppermint tea can soothe skin irritation. Make a strong solution of chamomile and peppermint, swish your face in it, and let it sit for a while on the skin. Plain oatmeal will also calm skin down. (Again, wash it off eventually unless you’re auditioning for a zombie movie.)

Fruit acids and enzymes can give you a natural “glycolic peel”. Next time you throw fruit in your Supershake, wipe your face with the pineapple or squished orange rinds. Seriously. Plain yogurt also works as a topical probiotic and exfoliating acid.

Eat, move, and live… better.©

Yep, we know… the health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn’t have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies — unique and personal — for you.

Cordain L. Dietary implications for the development of acne: A shifting paradigm. US dermatology review 2006;1-5.

Danby FW. Nutrition and acne. Clinics in Dermatology 2010;28:598-604.

Dubrow TJ & Adderly BD. The Acne Cure. Rodale. 2003.

Logan AC & Treloar V. The Clear Skin Diet. Cumberland House Publishing. 2007.

Bowe WP, et al. Diet and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;63:124-141.

Cordain L. Implications for the role of diet in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2005;24:84-91.

Costa A, et al. Acne and diet: truth or myth? An Bras Dermatol 2010;85:346-353.

Cordain L, et al. Acne vulgaris a disease of western civilization. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:1584-1590.

Adebamowo CA, et al. Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:787-793.

Steventon K & Cowdell F. Acne and diet: a review of the latest evidence. Dermatological Nursing 2013;12:28-34.

Burris J, et al. Acne: The Role of Medical Nutrition Therapy. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:416-430.

[/references]

Share