Humans have starved themselves, over-eaten, and purged for thousands of years. Yet it was not until the 20th century that extreme slenderness became a widespread cultural ideal. Now we know that disordered eating in the 21st century is a complex phenomenon with many causes and consequences.

I remember the following statement from a lecture in 2006:

“Use new information about eating disorders very carefully.”

Becoming aware of new information isn’t always a good thing in the world of eating disorders.

Some people learn new things about disordered eating and instead of using it to heal themselves, they add it to their destructive eating arsenal.

If you struggle with disordered eating and you think reading this article offers more risk than benefit, and/or you think this article may trigger problematic behavior, proceed with caution.

What is disordered eating and when did it start?

Anorexia

“Anorexia” comes from the ancient Greek orexis, or appetite. The prefix “an” denotes “without”; thus “anorexia” is literally “without appetite”.

Now we use the term to describe purposeful non-eating or avoidance of food.

Historical examples

We can track human anorexia back over 11,000 years.

Nomadic foragers migrated from location to location and the biological capacity to suppress hunger may have offered an adaptive advantage.

Fasting days have often been part of religious rituals and processes across cultures. Many traditional indigenous societies include occasional prolonged fasts in order to strengthen their self-discipline and/or achieve spiritual insight.

However, some groups and individuals tried to go without food longer and more frequently. For them, extreme food restriction was part of a daily routine that also included other forms of self-punishment.

The premise was that the body’s needs were somehow immoral and sinful, and thus forcing the body to endure pain, extreme deprivation, and humiliation was a good thing.

For instance, during the medieval period (approx. 5th century CE to late 1500s), early Christian saints often practiced extreme asceticism, refraining from as many fleshly indulgences as possible, and engaging in fasts lasting several days or more.

This extreme food abstinence was linked to other forms of self-punishment in the name of religious devotion. As one source notes regarding medieval asceticism:

The ordinary fasting cycles [of other religions such as Islam and Judaism] did not satisfy the needs of ascetics, who therefore created their own traditions… Manichaean monks won general admiration for the intensity of their fasting achievements. [Early] Christian authors write of their ruthless and unrelenting fasting, and, between their own monks and the Manichaeans, only the Syrian ascetical virtuosos could offer competition in the practice of asceticism. Everything that could reduce sleep and make the resultant short period of rest as troublesome as possible was tried by Syrian ascetics. In their monasteries Syrian monks tied ropes around their abdomens and were then hung in an awkward position, and some were tied to standing posts.

Ascetics would deliberately inflict pain or damage (e.g. looking at the sun until they went blind); live in crude, unpleasant conditions (such as in caves); and generally endure extensive psychological and physical torment. This torment, notes the source:

“…must be carried out with such ardour that the inner life becomes a burning lava that produces an upheaval of the soul and torment of the heart… Nothing less than extreme self-mortification satisfied the ascetic virtuosos.”

Binge eating & purging

Binge eating has been known for thousands of years. Historically it was related to cycles of scarcity and abundance.

Food insecurity can lead to over-consumption in times of plenty.

Like fasting days, many world religions also had feasting days. Among populations accustomed to frequent famines or food shortages, feasting days or times of abundance were undoubtedly a license to over-eat.

The modern-day equivalent, now that food is as close as the supermarket, is a cycle of extreme dieting followed by eating to excess. While not all eaters include the extreme dieting — some simply over-eat — a cycle of deprivation followed by over-eating is common.

Humans have also known for millennia about forms of purging — methods of forcing the body to expel what it has consumed. This includes using emetics (substances or methods of inducing vomiting), diuretics (which flush out body water), laxatives, and/or enemas.

Historically, some regarded purging as a “health promoting” practice.

This was depicted in the novel and film The Road to Wellville, which satirized the 19th-century purging-oriented practices of Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (inventor of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes).

Because of the reluctance to associate obesity with disordered eating, it wasn’t until the early 1990s that binge eating was understood to be separate from bulimia.

Modern understandings and diagnoses

The actual “diagnosing” of disordered eating began in the 1870s.

There are two recognized eating disorder diagnoses: anorexia nervosa (AN), which is self starvation, and bulimia nervosa (BN), which is binging and purging.

These diagnoses are incomplete. They reflect only two types of disordered eating, and focus mostly on extreme cases.

They do not encompass the countless individuals who struggle with other disordered eating patterns.

Health professionals can utilize a catchall diagnosis, “Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS).” Currently, binge eating disorder (BED) is simply a provisional diagnostic status under EDNOS. When the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is released in 2011 (or 2012), BED will have its own separate category.

The characteristics of disordered eating are listed below.

Why is disordered eating important?

Clinically defined “eating disorders” of any type are only a small proportion of the rate of disordered eating in the general population. Arguably, “disordered eating” of one kind or another defines the lives of many people in modern society.

A poll of 10,000 readers in a popular teen magazine revealed that:

- 30% would rather be thin than healthy

- 50% of the women between the ages of 18 and 25 said they would prefer to be run over by a truck than be fat

- 66% would rather be “mean” or “stupid” instead of fat

Individuals who watch TV three or more nights per week are 50% more likely than non-watchers to feel “too big” or “too fat.”

This negative self image and intense fear of gaining body fat can lead to dieting. Nearly 25% of those who diet will develop partial or full syndrome eating disorders.

Yet the National Institute of Mental Health spends less money on eating disorder research than any other condition it handles.

Research funding per case equates to:

- $0.74 cents for eating disorders

- $34.07 for autism

- $37.78 for bipolar disorder

How common are eating disorders?

In short, we don’t know. We can only guess.

Since doctors have no requirement to report eating disorders to health agencies, and since most people who suffer disordered eating never seek treatment, it’s hard to get accurate statistics.

Furthermore, extrapolating eating disorder statistics to the general population is tricky. Not all patients are captured in a clinical setting, and the ones that do seek help don’t always fall into a specific category.

Indeed, a recent study suggests that mental health disorders — which can include disordered eating — may be more common than we realize.

If we factor in the broad range of behaviors that make up disordered eating, the prevalence of disordered eating is thus probably quite high.

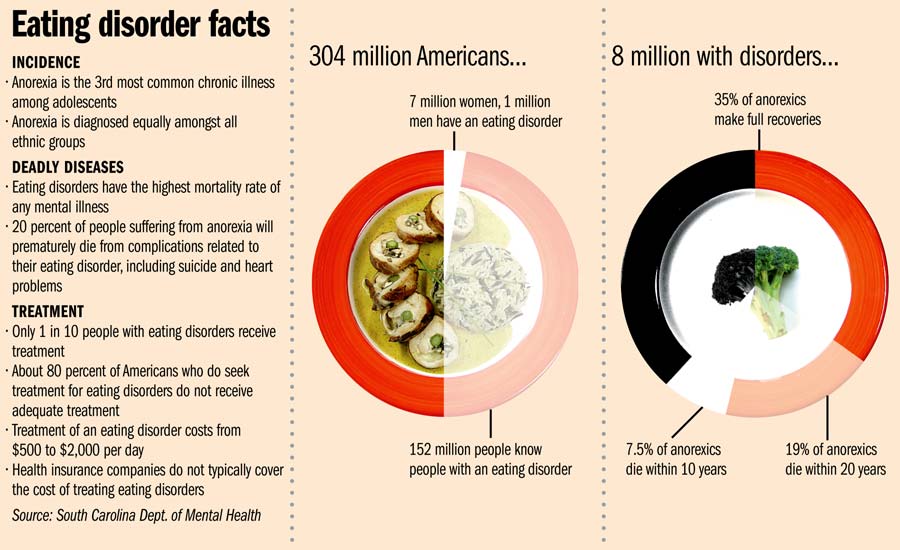

One estimate (see graphic below) indicates that only 1 in 10 people with eating disorders seek treatment.

The National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders states that approximately 8 million people in the U.S. have AN, BN, and related eating disorders. This means 3 of every 100 people eat in a disordered way.

Who is at risk?

About 1% of female adolescents have AN. Nearly 4% of college-aged women have BN. Data has indicated that almost 1/3 of female athletes may struggle with disordered eating.

For every 4 females with AN, there is one male. For every 8 to 11 females with BN, there is one male. Some studies indicate that up to 25% of adults with eating disorders are male.

Eating disorders used to be considered a “female problem”; however, males are increasingly affected, particularly as cultural norms shift to feature more and more lean and muscular male bodies in mass media. Some researchers have suggested, for instance, that “bigorexia”, or the perception that one’s body is too scrawny, may underlie many male bodybuilders’ quest for muscularity.

Nearly 90% of those with eating disorders report onset of illness by the age of 20 and the primary age groups affected are the teens and twenties. Yet increasingly, older people are reporting disordered eating.

All segments of society are affected by disordered eating: men and women, young and old, rich and poor, all ethnicities, and all socio-economic levels.

However, research suggests that worldwide, it’s the upper social classes of industrialized countries, particularly in Western countries but increasingly in Asian countries such as Japan who are most affected by disorders of food restriction and extreme dieting.

Studies have also found that even in regions and among ethnic groups that value plumpness, disordered eating is emerging.

One of the groups newly affected by disordered eating, for example, appears to be young women of Arab and South Asian origin now living in Western countries. One study remarks that this group is now vulnerable because these girls simultaneously experience the conflicting and multiple pressures of Western body-shape ideals, traditional family and cultural expectations, and the challenges of fitting in to a new society.

What you should know about disordered eating

Disordered eating is a complicated phenomenon. It should be viewed as a set of behaviours and experiences rather than a specific, narrowly defined medical condition.

While there are some features that these behaviours and experiences may share, people’s individual situations can vary widely.

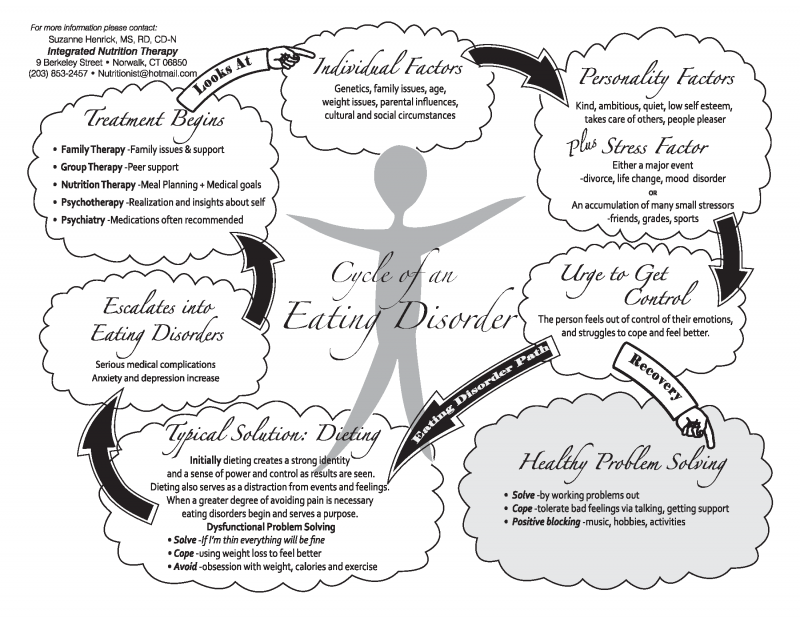

Eating disorders can develop from various factors, including:

- Family struggles

- Genetics

- Impaired body image

- Ineffective coping strategies

- Low self-esteem

- No feeling of personal identify

- Lack of perceived control

Physiological & psychological explanations

The exact origins of disordered eating are still unclear.

Some experts claim that genetics play a significant role in eating disorders. Those with a mother or sister who had AN are 12 times more likely than others with no family history of that disorder to develop it themselves. However, it’s not clear whether genetics is responsible, or whether the disordered eater is simply mimicking the behaviour and attitudes of other family members (or both).

Others argue that eating disorders might actually be due to underlying metabolic or digestive tract disorders.

It’s been suggested that those with AN have serotonin overactivity, leading to exaggerated satiety. They might also have excess activity in the brain’s dopamine receptors, leading to a drive for weight loss, but no pleasure from shedding the weight. Over-eaters may also have some disruption of dopamine, which is known to stimulate the body’s “wanting” response, or under-active satiety mechanisms.

Strict dieting and the inability to adjust to environmental stressors are two critical initiators for developing an eating disorder.

Restriction of food can cause food preoccupation, as any strict dieter can attest.

And food can become “drug-like” for those struggling to cope with stress. Some evidence links anxiety and depression with disordered eating.

Some have even suggested that disordered eating is not a “disorder” at all but simply the body’s “normal” attempt to cope with “abnormal” situations of modern stresses, cultural ideals, and food availability. In this model, disordered eating is actually a “mismatch” between Paleolithic physiology/psychology and modern lifestyle demands.

No single cause

What seems clear is that disordered eating can have many, interlocking, causes and manifestations. It’s a set of complex behaviours and experiences that can not and should not be over-simplified.

Cyclical nature

Disordered eating can often be cyclical.

Eaters may have disordered eating thoughts and behaviours daily, every few days, every few weeks, or even infrequently throughout their lives.

Some disordered eating appears during periods of stress and/or life transitions, then disappears again for a while when things settle down. These periods can include things like:

- adolescence

- midlife

- periods when identity or lifestyle changes (e.g. loss of a job, financial troubles, transition into parenthood, etc.)

- stressful interpersonal events (e.g. death of a loved one or relationship problems, etc.)

- etc.

Other disordered eating may follow a daily or regular routine (e.g. fasting all day followed by an evening binge; extreme dieting during the week followed by a weekend binge then a Monday morning purge, etc.).

Eating disorder types

Again, bear in mind that these are collections of symptoms that have been given a clinical label. Not everyone with disordered eating will fall neatly into these categories.

Many people will have a unique set of behaviours from all of these lists of symptoms, and the symptoms may change over time or with the situation.

In all cases, however, there are physical, psychological, behavioural, and lifestyle causes and consequences.

Anorexia nervosa

Characteristics

- Disturbed sense of body image

- Refusal to maintain a minimally normal body weight

- In women, amenorrhea (from food restriction)

- The individual will severely reject food, causing extreme weight loss, depressed metabolism and fatigue

- Weight loss

- Intense fear of weight gain

- Preoccupation with low calorie/sugar/fat foods

- Specific eating rituals and habits

- Excessive exercise

- Social/emotional withdrawal

Causes

AN can have causes rooting from biological, psychological and/or socio-cultural origin. There is a possible genetic link.

Individuals who develop AN may have psychological and emotional characteristics that contribute to its development, including low self worth or obsessive compulsive personality traits.

The Western culture cultivates the desire for thinness and muscularity.

Peer pressure and sports may also promote the desire to alter one’s body.

Anorexia athletica is the development of anorexia-like symptoms and behaviours in athletes. See below for more.

Consequences

AN has the highest death rate of any mental illness, with a mortality rate of between 6% and 20%. Other consequences include anemia, lung problems, dehydration, bone loss and fractures, abnormal heart rhythms, heart failure, amenorrhea, hypogonadism, constipation, nausea, electrolyte abnormalities and kidney problems.

Bulimia

Characteristics

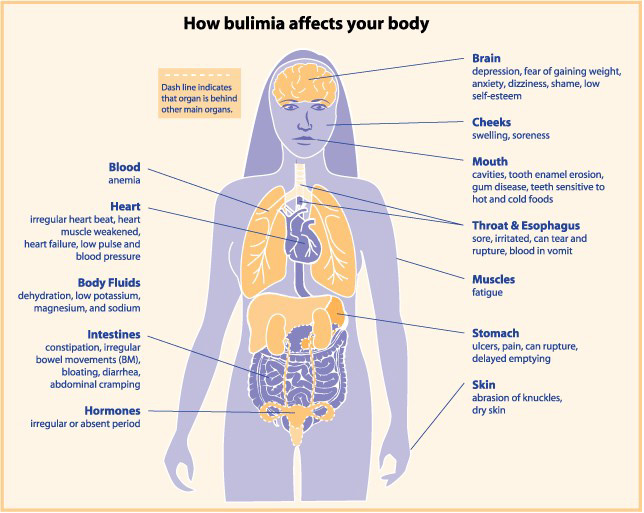

- Recurring episodes of binge eating during which the person consumes large amounts of food and feels unable to stop eating, followed by inappropriate compensatory efforts to avoid weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, laxative or diuretic abuse, vigorous exercise, or fasting

- Using food (either overeating or purging) as a major coping mechanism

- Patients are steadily and overly apprehensive about body shape and weight

- Patients are more likely to experience loneliness, irritability, passivity, sadness, and suicidal behavior

Causes

Those with bulimia are usually of normal weight status and tend to be well-educated.

Overweight parents (often mothers) sometimes teach their children to use food as a stress coping mechanism, or as a reward/punishment.

Codependency can be present, which is a dysfunctional pattern of relating to one’s own feelings, focusing on others or on things outside of themselves. Admission and guilt tend to be more common among patients with bulimia.

Biological causes have been suggested, e.g. disorders of neurotransmitters associated with reward, satiety and anxiety, such as dopamine and serotonin.

Consequences

Vomiting can lead to erosion of dental enamel, mucosal trauma from stomach acids, gingival recession, dental caries, dry mouth and salivary gland enlargement (a puffy face is common).

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances can occur, notably low blood potassium (which causes heart arrhythmias).

After a binge, the stomach can rupture or the esophagus can tear. This is often fatal. On a lesser scale, there may be damage to the esophageal sphincter that regulates food transport between esophagus and stomach, which can lead to gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Binge episodes increase gastric capacity, delay gastric emptying, blunt hormone release from the stomach and impair satiety response.

Binge eating

Characteristics

- Binging not followed with purging

- Binging consists of recurrent eating episodes that involve either eating more rapidly than normal, eating until uncomfortable, eating when not physically hungry, eating and then feeling disgusted/guilty/depressed

- Eaters often report “cognitive dissociation”, or the feeling that they are on “autopilot” while binging, and oblivious to pleas from part of their brain to stop

- BED is four times more common and persists longer than AN and BN

- While binging on high-fat/high-sugar foods is common, bingers may also consume less-appetizing foods such as food that is still frozen, food from other people’s plates, or even foods out of the garbage

Causes

Binge eating contributes to excessive calorie intake and is most common in obese persons. The onset is usually beyond teen years.

Individuals with this disorder tend to be distressed by it, with depression being a common symptom. Researchers have begun to classify BED as a “major public health burden.”

Chronic dieting may predispose binge eating.

Depression is not only a symptom but a common antecedent.

More than 25% of patients in weight control programs binge at least twice per month. Many times, a history of parental or personal alcohol abuse is noticed. Other traumatic events, years of unusual stress, or mood disorders can also be involved.

Consequences

The physical outcomes of BED include diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and other health ailments.

After a binge, the stomach can rupture or the esophagus can tear. This is often fatal. Binge eaters are also more prone to gastro-esophageal reflux (GERD) and other GI disorders, due to the volume and speed of consumption.

Psychologically, bingers often experience depression, since many people are always struggling to reduce body weight. They may become anxious in anticipation of upcoming

Thus, lifelong weight cycling and psychological distress are typical when the disorder is uncontrolled.

Anorexia athletica

There are two related forms of anorexia athletica. One is defined by the use of excessive exercise to maintain body weight; the other is defined by disordered eating among recreational and competitive athletes.

In both cases, exercise is usually part of a general attempt to control body size/weight, or a precipitating factor in disordered eating behaviours.

Characteristics

- When an individual no longer chooses to exercise but feels compelled to do so

- Often, exercise in excessive amounts, especially exercise that is associated with weight loss (e.g. several hours of cardio a day)

- The patient will struggle with guilt and/or anxiety if they do not exercise

- Use of excessive exercise, usually along with dietary restriction, to maintain a low body weight/fat

- Excessive exercise may follow a similar cycle as binge-purge, with exercise following a binge episode

Causes

Exercise anorexia is a compulsive behaviour and many individuals do it to gain more control over their lives. It can be provoked by dieting at an early age, comments about body shape by a professional/coach and sport specific training.

Athletes engaging in team sports and sports/physical activities that emphasize either weight classes or body image (e.g. wrestling, swimming, dance) are most vulnerable, particularly if parents, coaches, or peers are focused on weight or body size.

Consequences

The health outcomes include dry hair, dry skin, hair loss, digestive difficulties, slowed heart rate, low blood pressure, dehydration, kidney problems, insomnia, joint weakness, suppressed immune function, and nutrient deficiencies.

Athletic performance is eventually also affected, as athletes may suffer recurring injuries and illnesses, cognitive impairments, and poor recovery from training.

Prevention and treatment of eating disorders

Depending on the severity and duration of the eating disorder, treatment varies.

Generally, however, treatment should be multi-factorial and address physical, psychological, and lifestyle factors.

With advanced AN, treatment typically has two phases:

- Phase 1: A short-term intervention to restore body weight and prevent death.

- Phase 2: A long-term therapy to improve psychological functioning and prevent relapse. Tube feedings are sometimes necessary.

Usually, a team approach is utilized with a physician, nurse, dietitian and psychiatrist.

Two approaches for BN treatment are psychotherapy and antidepressant medications. Sessions can be done over a 6 month period and the antidepressants can be helpful for long-term results.

No standard treatments are involved with BED and exercise anorexia. Conventional weight management programs or professional counseling may be involved. The treatment method is determined by the patient.

Summary and recommendations

“When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.”

As with other types of addictions, there’s not much anybody can do until the person with the disordered eating wants to change.

Confrontation and harassing generally don’t help. Nor does well-meaning advice such as “Get over it” or “You should love your body”.

One of the best things to say to someone you suspect has disordered eating patterns is:

“Let me know if there is anything I can do to help.”

Direct statements or judgments about body size or eating habits will most likely elicit resistance.

If you are concerned about your own eating patterns, and suspect they are disordered, we suggest seeking out resources to assist in recovery.

Strict dieting will likely create further problems. Remember, the disorder probably extends beyond food.

Find books, a counselor and/or a support group that can assist you in making a recovery. It’s tough, but it’s worth it.

Extra credit

Besides the obvious repercussions of disordered eating, other scary stuff can happen. Check out this case report from 2008:

A 24 year old female with a history of BN and vomiting came to the emergency room with marked abdominal distension. Her stomach had ruptured. A large nasogastric tube was inserted and 9 liters of viscous gastric contents were drained out. Three months later she experienced paralysis on her right side and loss of language skills. She had experienced a brain hemorrhage due to bacteria spreading from the stomach rupture.

Inpatient treatment for disordered eating can reach $30,000 per month.

Stress can trigger binge eating.

No medications appear to be effective for treating AN. Medications may be useful for BN and BED. Behavioral therapy seems to be the most effective option.

Some data has indicated that vegetarian adolescents may be more likely to display disordered eating attitudes and behaviors than non-vegetarians.

Eat, move, and live… better.©

Yep, we know… the health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn’t have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies — unique and personal — for you.

Click here to download the special report, for free.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Share