The squat is arguably one of the best exercises for the lower body. When you squat you use pretty much every muscle from the waist down.

The big kahunas — the gluteus group and deep hip muscles, quadriceps, and hamstrings — provide the drive. Other muscle groups, such as the abdominals, spinal musculature, and calves kick in to stabilize things and keep you from falling over.

Sounds like a great exercise to be doing! Right? It is a fantastic exercise, but it’s also one of the most challenging and controversial. People have loads of questions about it. Should I squat or will squatting make my thighs too big? How deep should I go? Which type of squat is best for me?

Research question

Well, I’ll try to answer at least one question with this week’s review, which compares the biomechanics of the back and front squats.

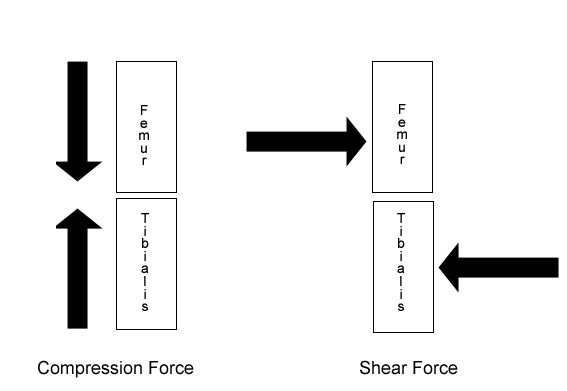

Before we get into the study there are a few things you need to know. In particular, you’ll need to be familiar with two very basic biomechanics terms: compression forces and shear forces (see figure below).

Compression forces, as their name implies, are forces that flatten or squeeze a material. In the case of the knee, compression forces squeeze cartilage.

Shear forces (stresses) are forces that run perpendicular (90°) from the material — in this case the knee. Imagine a stack of books. Now imagine trying to remove one book from the middle of the pile without disturbing the others. You probably wouldn’t try to retrieve that book by grabbing its edge and pulling it upwards; you’d probably push the book sideways and try to slide it out, right? That’s shear force.

Gullett JC, Tillman MD, Gutierrez GM, Chow JW. A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2009 Jan;23(1):284-92.

Methods

The usual suspects were used for this study: nine men and six women, all young (about 22 years old), healthy, and most likely university students. But here’s a cool thing: All participants were required to have at least one year’s experience with front and back squatting at least once a week. Yup, everybody in the study had been back and front squatting once a week for at least 52 weeks. I’m surprised they found 15 people!

While the lifters were “experienced” (unlike the commonly used untrained subjects), they weren’t huge people. Their average height was 171.2 cm (5’7”ish) and average weight was 69.7 kg (149.25 lb). Nor were they unusually strong people. On average the lifters’ 1 repetition maximum was 90% of their mass (61.8 kg -136.2 lb) for the back squat and 70% of their mass (48.5 kg – 106.9 lb) for the front squat. Not exactly world class but hey, we all have to begin somewhere, right? At least these folks were squatting, which is a great start!

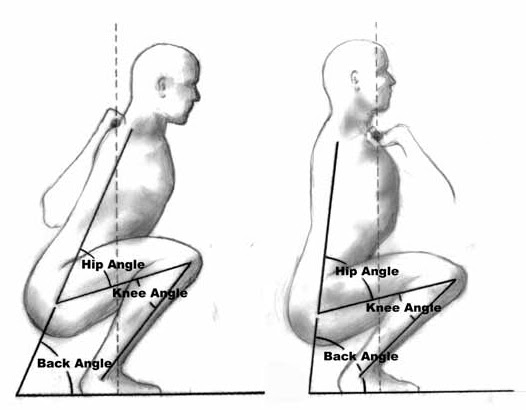

Procedure for back and front squats

For this study the procedure or technique for back squatting involved “…the barbell being positioned across the shoulder on the trapezius slightly above the posterior aspect of the deltoids, and allowing the hips and knees to slowly flex until the thighs are parallel to the floor. The individual then extends the hips and knees until reaching the beginning, with emphasis with keeping the back flat, the heels on the floor, and the knees aligned over the feet”.1 In other words, lifters had the barbell in a “high bar position” and squatted until parallel with “good technique.”

For front squatting the technique was described by the authors as involving “the lifter positioning the barbell across the anterior deltoids and clavicles and fully flexing the elbows to position the upper arms parallel to the floor,” using what some might describe a “clean grip” (as opposed to the crossed-wrist style grip used by some bodybuilders). The rest of the technique was the same as the back squat.1

When comparing the back and front squat in this experiment it all comes down to barbell placement. In the back squat, the barbell is behind the neck, across the trapezius. In the front squat the barbell is in front of the neck, across the front of the shoulders.

The measurements

This experiment measured two things: muscle activity and forces placed on the knee. Muscle activity was measured by electromyography (EMG). In particular, researchers observed the muscles of the quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis and vastus medialis), the hamstrings (biceps femoris and semitendinosus), and the lower back (erector spinae).

To determine the forces on the knee, researchers performed a biomechanical analysis of the squats using video recordings. To make analysis possible, they placed (aka stuck) spherical reflective markers (aka shiny balls) over the greater tochanter (hip), midthigh, lateral knee, midshank (mid-shin), second metatarsal head (second toe knuckle –- if toes have knuckles), lateral malleolus (outside ankle bone) and calcaneus (heel) on each lifter’s right leg. Participants were then asked to lift “normally” with six shiny balls stuck to their right leg while being video recorded. Oh, they also had one foot on a force plate.

I’m not picking on the experimenters, but I always find it funny how in a lab setting experimental subjects have a bunch of things stuck to them; they get poked, prodded, and starved; and then they’re asked to exercise “normally” or the results are interpreted as such. So far though, this is the best we’ve got, but be careful how you interpret some of these results and their application to the real world.

One last thing about the measurements: before the day of EMG and biomechanical testing the lifters’ 1 repetition maximum (1RM) was figured out. For the testing the lifter did 70% of their 1RM.

Results

Interestingly (aka weirdly), EMG data showed no difference between front and back squats in any of the activities of muscles measured. That’s right, no difference in any of the quadriceps, hamstring or back muscles –- at least from a statistics standpoint. If you look at the data closely, there are some differences that in a larger group might be statistically significant. In cases with small differences between measures, statistics usually requires more samples –- in this case lifters -– to determine a difference. (But good luck finding more people with such desirable squat histories!)

Comparing just the averages, we find the back squat had higher hamstring activity (biceps femoris and semitendinous) compared to the front squat. The back squat also had lower quadriceps activity in two of the three muscles measured (vastus lateralis and rectus femoris), while vastus medialis activity was nearly identical in both squats. Last, front squats had higher back muscle (erector spinae) activity compared to back squats.

Analysis of biomechanical data found there were higher compressive and knee extensor moments in the back squat compared to the front squat. However there was no difference in shear stress on the knee, which was actually fairly low -– a lot lower than, say, knee extensions.

| Back squat | Front squat | |

|---|---|---|

| EMG data: muscle activation |

||

| Hamstrings | Higher | Lower |

| Quadriceps | ||

| Vastus lateralis | Lower | Higher |

| Rectus femoris | Lower | Higher |

| Vastus medialis | Similar | Similar |

| Low back (erector spinae) | Lower | Higher |

| Biomechanical analysis | ||

| Compressive force | Higher | Lower |

| Knee extensor moments | Higher | Lower |

| Shear stress | Similar | Similar |

Conclusion

There are two ways of looking at the EMG data:

- There is no difference in muscle activation between front and back squats.

- Or, front squatting less weight results in the same activation as back squatting more weight.

While front squats showed no difference, or marginally less muscle activation, you have to remember that lifters also used less weight. So it really isn’t a surprise that compressive forces on the knee during front squats are lower.

The authors suggest that if you have knee problems, such as ligament damage or meniscus tears, or if you have problems with osteoarthritis, then you may want to stick with the front squat since compressive forces can damage knee cartilage.

Another thing: if you look just at squats in general, both front and back, forces on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) (as measured by posterior shear forces) are low. Shear forces are so low, in fact, that many experimenters suggest that squats are safe for patients with ACL damage.2 So much for squats being bad for your knees! Oh, and machine squats were found to have 30-40% higher shear forces than free weight squats.3

Now isn’t it time you went and worked on that squat? Maybe the experimenters will be looking for more participants and you’ll want to be ready…

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Learn more

Want to get in the best shape of your life, and stay that way for good? Check out the following 5-day body transformation courses.

The best part? They're totally free.

To check out the free courses, just click one of the links below.

Share