As his weight climbed to nearly 300 pounds, Dominic Matteo thought he knew how to turn things around: Just stop eating chips, ice cream, and other highly processed foods.

“I’ll will myself through this,” he told himself.

Then he’d see the ice cream in the freezer and think, ‘Just one spoonful.’ Soon Matteo was staring at an empty container and wondering, ‘Why am I so weak?’

But Matteo’s willpower wasn’t the problem—his kitchen was. It was stocked with tempting junk foods, and it needed a serious overhaul.

Here’s the thing: Back then, Matteo didn’t believe a kitchen makeover would actually work. It sounded too easy.

He tried it anyway, though… and went on to lose over 100 pounds.

“If I hadn’t done that experiment, I probably wouldn’t have been successful,” says Matteo, who’s now a Precision Nutrition Level 2 Master Class coach. “It’s all about self-discovery and awareness.”

At Precision Nutrition, we often use experiments to help our clients discover important clues about what they really need (and don’t need) to reach their goals. Such experiments serve as powerful tools for uprooting the limiting and often false beliefs that tend to derail lasting habit change.

In this article, you’ll find three of our most transformative experiments. Try them yourself (or use with a client). What you learn may help you finally clear your biggest hurdles… even if the experiments sound too easy to work.

(Want more helpful nutrition, health, and coaching strategies? Sign up for our FREE weekly newsletter, The Smartest Coach in the Room.)

Limiting Belief #1: “If I had more willpower, I could stop eating so much junk food.”

Many of us assume, much like Matteo did, that willpower is something we’re either born with… or we’re not.

So when we find ourselves reaching for the second (or third … or fourth … or fifth) chocolate chip cookie, we beat ourselves up for being “weak.”

But portion control and healthful food choices are less about motivation and willpower and more about your environment. Give this experiment a try, and you’ll see what we mean.

The experiment: Do a kitchen makeover.

Use this two-step process to clean out your fridge, pantry, freezer, and other places you stash food. In the process, you’ll make some foods a lot harder to eat and other foods a lot easier to eat.

Step 1: Make a list

Determine your red, yellow, and green light foods.

But keep in mind: At Precision Nutrition, we don’t believe in universally good or bad foods. Everyone’s red, yellow, and green lists will be different.

Here’s how to identify yours:

Red light foods = “no go” foods. These are foods that present such a difficult challenge for you that they just aren’t worth the struggle. Red light foods may not work for you because:

- They don’t help you achieve your goals

- You always overeat them

- You’re allergic to them

- You can’t easily digest them

- You just don’t like them

Ultra-processed foods often fall into this category.

Yellow light foods = “slow down” foods. Maybe you can eat a little bit of these and stop, or you can eat them sanely at a restaurant with others, but not at home alone.

Green light foods = anytime foods. They’re nutritious and make your body and mind feel good. You can eat them normally, slowly, and in reasonable amounts. Whole foods usually make up most of this list.

So what if your partner or kids love the foods that you want to get out of the house?

Matteo confronted this exact predicament. Here’s what he suggests.

Talk about it. Explain that you want to make a change—and why. You might say, “I really need your help. I can’t do this alone.”

Take small steps. Focus on removing or reducing a couple of foods at a time rather than every single red light food at once.

Compromise. For example, rather than purchasing half-gallon containers of ice cream, Matteo’s family now buys eight single-serving cups—just enough for each family member to consume two single-serving desserts a week.

Stash it out of sight. If you must keep a red light food in the house, make it as difficult to access as you can. For example, you might keep chips on a shelf in the basement rather than in the kitchen. One of Matteo’s clients asked his wife to store desserts in a safe for which only she knew the combination.

Step 2: Get cleaning.

You’ll probably need a large garbage bag (maybe a few!) and a compost bin, if you have one.

First, get rid of the red light foods. If you struggle with the idea of wasting food, consider donating unopened, non-perishable, unexpired items to a charity. Compost what you can’t donate.

And remind yourself: Overeating is no less wasteful than trashing the food, given your body doesn’t actually need the calories. Plus, you just might find, as Matteo did, that your kitchen purge actually saves you money over time because you’ll stop buying certain foods.

Next, deal with the yellow light foods. You have a few options here. You can remove them, keep them in smaller quantities to prevent overeating, or put them somewhere hard to see and reach (on a high shelf in an opaque container, for example).

Lastly, stock up on your green light foods. Put these foods front and center and take steps to make them easy to grab and eat.

For example, maybe you make your own trail mix, storing it at the front of the pantry where you’re more likely to see it. Or, perhaps you peel a couple of oranges and keep them toward the front of the fridge, for easy snacking during your laziest moments. Or maybe you keep a half dozen hard-boiled eggs on the ready.

One note: Don’t overdo it when purchasing new green foods, especially produce, as they’re likely perishable (unlike most of the red and yellow foods you’re replacing). Remember, it’s okay to start small and build from there.

Step 3: Take notes.

The next time you get a craving for a red or yellow food, notice what happens. Do you reach for something on your green light list, since that’s what’s right in front of you? Or do you drive to the store to get food you crave? Or… do you decide not to eat anything at all because it requires way too much effort?

The lesson: Your environment makes it harder to practice healthy eating habits.

“Understanding that your environment guides your decisions can facilitate better actions,” Matteo says.

What he’s getting at is something we refer to as Berardi’s First Law (named after our co-founder, John Berardi, PhD):

If a food is in your house or possession, either you, someone you love, or someone you marginally tolerate, will eventually eat it.

There’s also a corollary to this law:

If a healthy food is in your house or possession, either you, someone you love, or someone you marginally tolerate, will eventually eat it.

This is why relying on willpower or motivation is a fundamentally flawed plan. No matter how much or how little willpower you actually have, you’ll eventually default to the easiest food options, especially when you’re tired. Or stressed. Or ravenous.

By removing red light foods, you make the choice to eat green foods so much easier—almost no willpower required.

Limiting Belief #2: “I hardly eat anything, and I still can’t lose weight.”

Feeling this way can be incredibly frustrating and confusing. Sometimes, it even stops people from trying to get healthier altogether.

But in every case, the principle of energy balance applies:

When you eat more calories (energy) than you expend, you gain weight. And when you eat fewer calories than you expend, you lose weight. (Which sounds way simpler than it is, of course.)

So what gives? Let’s find out.

The experiment: For one week, track everything you eat.

All you have to do: Write down what you eat every day for a week.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. You’ve heard this advice before—maybe hundreds of times.

But have you really done it? By actually writing it down (versus keeping a mental tally)?

For every single meal and snack?

Every day?

For a whole week?

If not, give it a try. It’s actually a lot easier than it sounds. You can write it down in a notebook, use a record-keeping app like MyFitnessPal, or even just snap a photo of everything you eat.

Make sure to include everything you eat and drink. Don’t forget to record the cream and sugar in your coffee, the dressing on your salad, and the lone fry (or was it eight?) you stole off your kid’s plate.

(Note: Unless you enjoy it, we’re not recommending you track this way regularly. This is just a short-term experiment.)

Treat these notes as if you were a scientist. This isn’t about judging your food choices. It’s merely about noticing them. Be kind, curious, and compassionate with yourself.

For the most accurate snapshot of your eating habits, try to do this during a typical week without any big events, and don’t change how you normally eat just because you’re keeping track.

At the end of the week, take a look at your log. Is it in line with how much you thought you were eating?

The lesson: It’s easy, and incredibly common, to underestimate how much you eat.

Research shows that, on average, people underestimate their food intake by around 47 percent—for all sorts of understandable reasons.

First, mindless nibbles can be even less memorable than the storage location of our car keys.

Second, though humans are great at a lot of things, estimating portion sizes just isn’t one of them. We don’t always recognize how caloric certain foods are (hi, peanut butter), and sometimes we deceive ourselves. (‘I had, like, five chips… not three-quarters of the bag… right?”)

Point is, this is a real thing. And it happens to a lot of people—even dietitians.

That’s why many people need nutritional guard rails—calorie counts, macros, or hand portions—to guide what and how much they eat… at least for a little while. Here at PN, we use hand portions to help clients make better food and portion judgments. (We’ve seen some incredible transformations using this method alone.)

If you haven’t already checked out our Nutrition Calculator, go ahead and plug in your goals and personal info. You’ll get a full report of how much to eat, along with the corresponding hand portions, and everything you need to know about how they work.

Using this approach, in combination with mindful eating practices like eating slowly and to 80 percent full, can help you eat in a way that makes weight loss feel more effortless.

Want to keep learning more about yourself? Try the following to keep gathering intel.

Experiment: Eat nothing but sugar packets (read: pure sugar) for a day. (Good luck!)

What it shows: Sugar itself may not really be a problem food for you. Read: Most people won’t stuff themselves with sugar alone. Instead, it’s more about what the sugar is mixed with. For example, you may be okay consuming it when it’s in fruit, yogurt, or even ketchup, but not when it’s inside your personal red light foods like cookies, chocolate, or ice cream.

Experiment: Eat slowly every day for a month, trying to make every meal last a little bit longer. (Start by taking a breath between bites.)

What it shows: You may discover that you feel more satisfied sooner, so you eat less automatically. You may also notice eating slowly brings up uncomfortable feelings—ones you’ve been quashing with food.

Experiment: Use this article to make breakfast a little bit healthier.

What it shows: You don’t have to do a complete 180 in order to see progress. Could you swap cold cereal for oatmeal? Could you have fruit instead of hashbrowns? Could you try eggs on a bed of greens instead of with a bagel? It’s not just about the substitutions; it’s about being thoughtful about what you eat… before you eat. Small changes, done consistently, pave the way to lasting habits.

Limiting Belief #3: “I seriously can’t handle being hungry.”

Hunger is a lot of things: annoying, uncomfortable, distracting…

One thing it’s not: such a big deal that you should do everything in your power to avoid ever experiencing it.

Problem is, hunger feels like a big deal. Some clients have even told us that hunger feels like an emergency. They worry that if they don’t eat right away, their hunger will continue to get worse and worse and worse until… they die.

Or wish they could.

For these reasons, many people eat as soon as they feel even the slightest pang—physical or mental. That often means they consume more than really needed, which leads to weight gain (or stalls fat loss). They also reach for whatever they find first (see experiment #1).

But what happens when you don’t immediately meet hunger with food? Let’s find out.

The experiment: Try fasting for a day.

We know it sounds scary. Nothing bad will happen—promise.

We include this experiment, lovingly called “fasting day,” in our year-long coaching program. Over the years, our coaching clients have told us this day is one of the most impactful experiences of the entire program.

Here’s how it works: Consume no calories for 24 hours.

Zero. Nada. None.

Enjoy calorie-free drinks such as water, flavored water, unsweetened tea, or plain coffee. But other than that, avoid all food and caloric beverages.

Obviously this isn’t something we recommend long-term. It’s just one day.

And it just might be the most challenging and insightful day you’ve had in a long time.

A couple of important caveats:

You can do this on a schedule that works for you. For example, you could fast from dinner to dinner, or lunch to lunch. If 24 hours feels like too much, consider just skipping a meal or two instead. This isn’t about getting it “perfect.” Also, it might go without saying, but you probably shouldn’t try this experiment on a day when you need to be 100% “on your game,” such as when you’re flying a plane or doing open-heart surgery.

Fasting isn’t right for everyone. Do not fast if you:

- have a medical condition that requires you to eat

- struggle with disordered eating and have been told never to fast

- know that periods of food restriction—even if done carefully and consciously—can lead to bingeing later on

The lesson: Hunger isn’t an emergency.

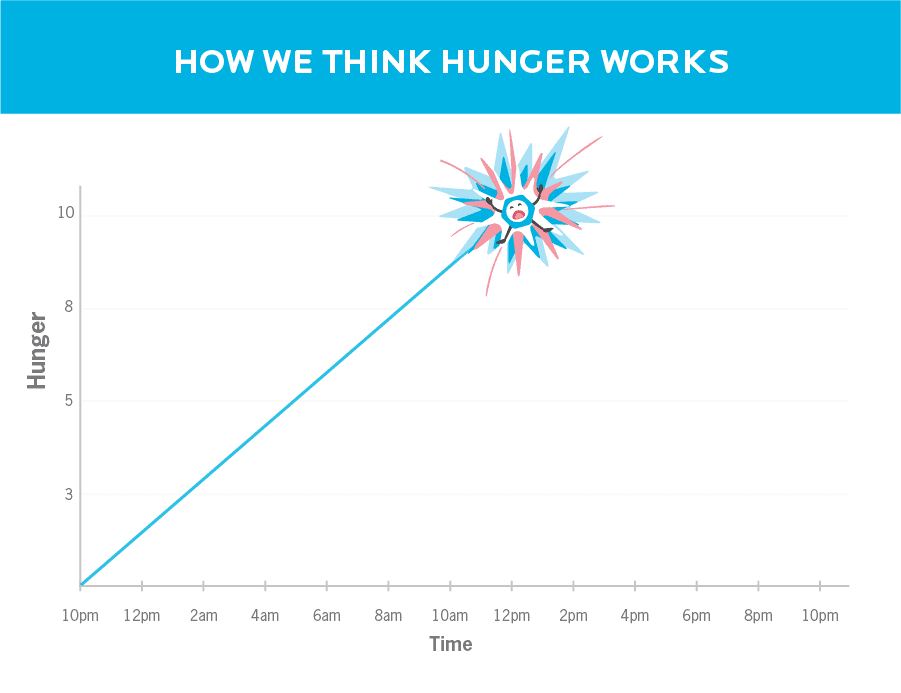

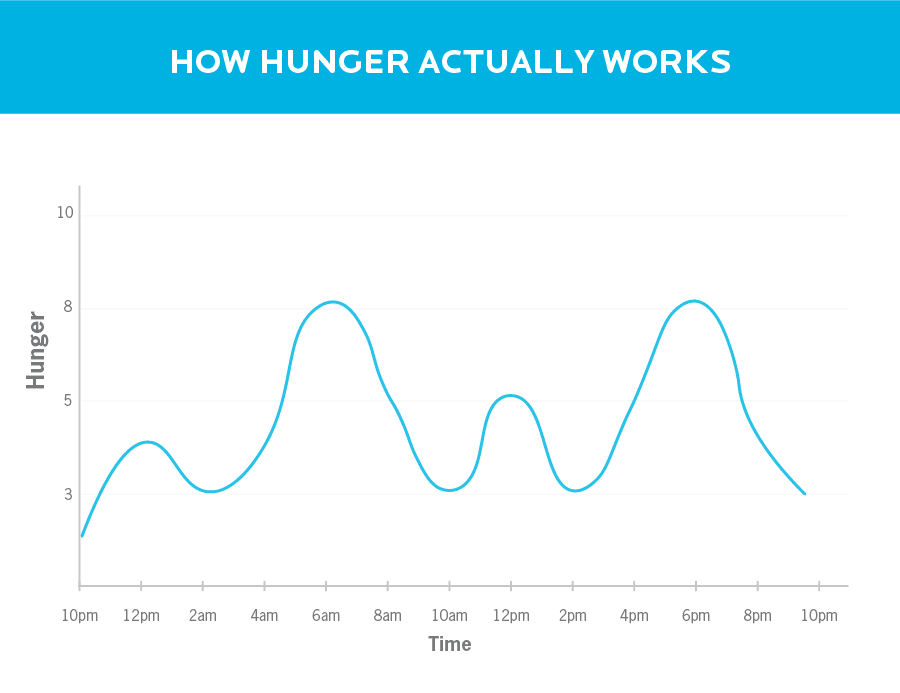

It’s natural to worry that hunger will keep getting worse and worse—making us feel lousy and preventing us from getting anything useful done.

But hunger doesn’t work like that.

Hunger hormones are released in waves based on when our bodies are expecting food.

As you’ll probably experience while doing this experiment, hunger is strongest around the three- to four-hour mark of a fast. Then it subsides.

It’s an incredible feeling (and often a great relief) to learn that you can feel hungry—truly hungry—and choose not to do anything about it.

There are several benefits here:

- Benefit #1: If the available food choices don’t make sense for you, you know you can wait until something better is available. No biggie.

- Benefit #2: You learn what true hunger feels like. This awareness can help you distinguish psychological hunger (“I feel like eating something”) from physiological hunger (“My body is telling me it’s time to eat”).

- Benefit #3: If it’s not “time to eat,” waiting until your next meal or snack won’t feel like a problem. This is not only convenient if hunger strikes somewhere food isn’t accessible (such as on your commute), but can also be extremely helpful if you’re trying to lose fat.

Keep experimenting, keep growing.

You can probably see why we’re such big fans of self-experimentation: It’s quite literally a win-win. You’ll either get a reaffirming boost of confidence and confirmation that you’re already on the right track, or you’ll get valuable information about how you can change things for the better.

By simply paying attention to how experiments make you feel, you empower and energize yourself to make better, more informed choices.

And remember: Self-experimentation isn’t about getting it perfect. It’s about finding out what works for you, and then putting it into practice—one small step at a time.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

You can help people build sustainable nutrition and lifestyle habits that will significantly improve their physical and mental health—while you make a great living doing what you love. We'll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification. (You can enroll now at a big discount.)

Share