What are sweeteners?

Sweeteners are substances used to improve the palatability and shelf life of food products.

Sweetness balances bitterness, sourness, and saltiness, and most humans prefer sweet tastes.

The osmolarity (the solute concentration) of sweeteners means that they usually inhibit bacterial and mold growth.

Sugars occur naturally in many plant foods; we get most common sweeteners by processing these plants (such as agave cacti, maple trees, sugar cane, coconut palms, sugar beets and corn) to extract and condense the sugars. In the case of honey, bees do the work of extracting and processing flower nectar for us.

For example, we make maple syrup by tapping tree sap when it starts to run through trees in the spring as the weather warms up. Then, we boil off most of the liquid until we have a highly condensed sugar solution. We can also make maple sugar (in other words, crystallized syrup) simply by removing all the liquid altogether.

In this article, we’re going to look at naturally occurring sweeteners (i.e. refined from plant sources) rather than artificial sweeteners (i.e. created in a lab).

Most commonly, this means some combination of glucose, fructose, or sucrose.

A brief history of sweetening

Honey was likely the first naturally occurring sweetener we added to food/drink. However, we probably didn’t eat it often — after all, it required sticking one’s hand into a beehive, and it was often only available in warmer months.

Indigenous people in northern North America harvested tree sap for syrup that they used as food and medicine, a skill they later taught to English and French settlers.

Before refrigeration, people commonly dried fruits, soaked them in alcohol, or cooked them down to a condensed liquid (such a syrup or jam) to preserve them. These preserved fruits were often used as sweeteners.

But by far, the biggest change to the human diet was the cultivation and trade of sugar cane and refined sugar.

By about 6000 BCE, farmers began to cultivate sugar cane in parts of Southern Asia. Some sources report that crystallized sugar was used about 5,000 years ago in India.

Arab traders brought sugar to the Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, Egypt, North Africa, and Spain around 800 CE, and the crop quickly caught on.

Colonizers brought sugar cane to the tropical regions that they explored and settled. Sugar cane became a valuable cash crop (usually harvested by slave labour) in warm-weather regions worldwide. For instance, trade data show that in the year 1700, brown sugar and molasses made up over 10% of food imported to England from tropical countries.

After the first sugar refinery was established in England in 1544, the British became prodigious consumers of sugar relative to the rest of Europe, swilling down vast quantities of sweetened tea, rum punch, malt, and molasses spirits.

Corn sweeteners didn’t make it into food until the 1920s. High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) wasn’t discovered until 1971. In 1982, when the cost of sugar imports jumped, it became cheaper to sweeten food/drink with domestic HFCS.

Today, beet sugar provides about 30% of world granulated sugar.

Why are sweeteners so important?

Sweetener consumption in the past was limited to fruit and honey, although people in tropical regions could also consume sugar cane.

Since 1970 there’s been a 14% increase in total energy consumption from all sweeteners. Now added sweeteners comprise nearly 20% of our diet. Yup, this means almost 1/5th of the food and drink we ingest is added sweeteners.

How much sugar is in your soda?

Of all the carbohydrate foods we consume, 32% are actually added sweeteners. Let’s hope the other 68% are quinoa and buckwheat.

High fructose corn syrup (HFCS)

The development of HFCS has been one of the most significant changes to our food supply in the last century.

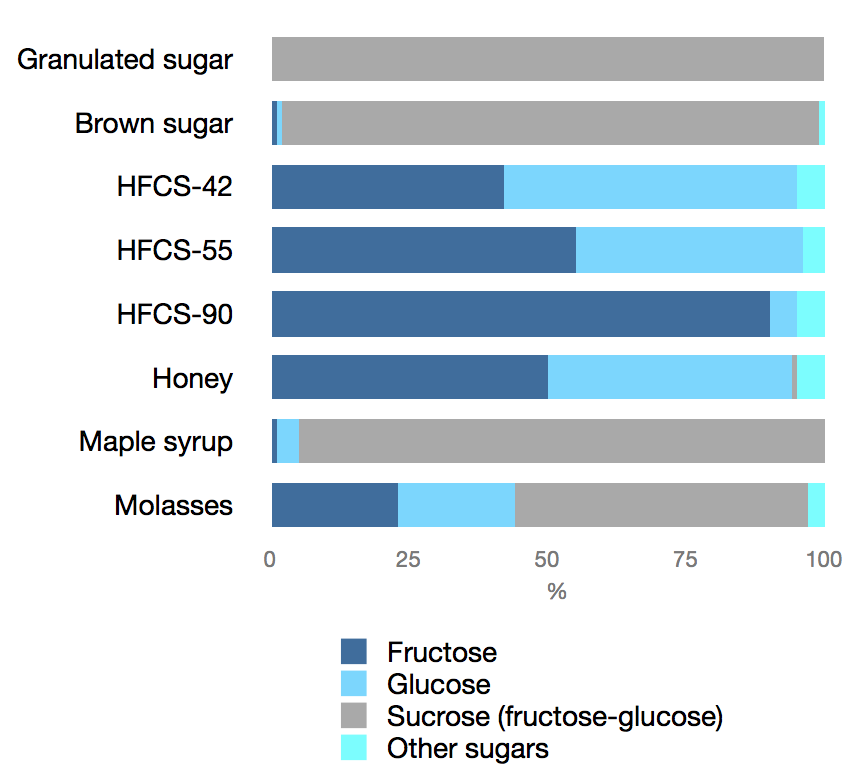

HFCS is actually a combination of fructose and glucose, and there are different types of HFCS depending on the proportion of fructose.

These different types are named according to the proportion of fructose they contain relative to glucose. Thus, HFCS-50 is 50% fructose; HFCS-90 is 90% fructose. HFCS-50 is approximately as sweet as table sugar, which is also made of glucose and fructose (in the form of sucrose).

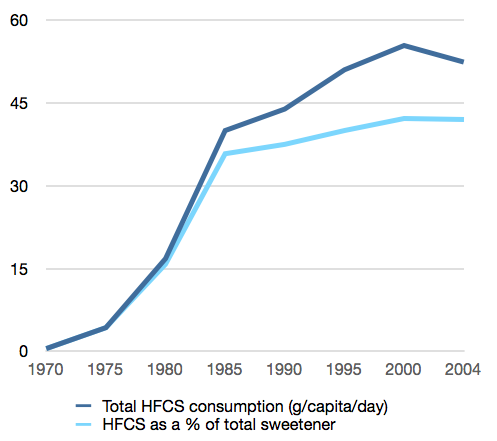

Extensive research has documented the large amounts of added caloric sweeteners in the diet over the past two decades. HFCS consumption increased during the 1980s and 1990s, only because it served as a replacement for table sugar.

HFCS intake has actually declined in recent years. And for all of us who love correlations, body fat is still rising in North America. So, while some say HFCS is the culprit behind more body fat, this doesn’t seem to be accurate.

Nevertheless, it’s hard to see how the sweetener consumption trends benefit us.

What you should know

“Natural” = “healthy”?

Sugars are technically “natural” in the sense that they originate in a plant (or in animals, in the case of sugars such as lactose). However, the refining process results in a chemical composition that is “unnatural” (as far as our bodies are concerned).

Thus, just because sugars come from plants, it doesn’t mean that they are good for you — especially in large amounts.

For example, eating 5 bananas will give you 85 g of sugar. That’s 3/4 of a cup of sugar. (In fact, eating too many high-fructose foods, like sweet fruits, also can give you diarrhea — the fructose combines with the fibre and your intestinal water to create the “perfect storm”.)

On the other hand, it doesn’t mean that you should fear small amounts of naturally occurring sugars in their native forms — for example, an apple or a carrot.

Chemistry matters

One of the most important things to understand about sweeteners is that their chemical structure affects the way the body processes and stores them. (See All About Carbohydrates and All About Fructose for more.)

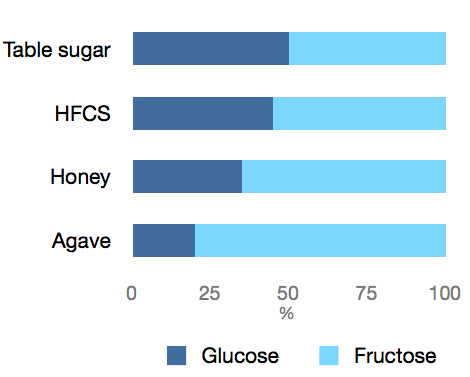

As the chart below shows, different sweeteners have different proportions of sugar types.

For instance, although honey and maple syrup are both “natural”, they have quite different sugar type profiles. Honey is about 50% fructose, while maple syrup is mostly sucrose.

Proportion of sugar types in common sweeteners

In one sense, sugar is sugar is sugar, and there’s no difference between sucrose in sugar cane and sucrose in your sugar bowl. However, it’s critical to understand that different sugars also act differently in the body.

What the glycemic index doesn’t tell you

The glycemic index (GI) is a measure of how quickly a food is broken down to glucose in the body. Even though fruits and vegetables may eventually break down into glucose, they have a low GI.

Some sweeteners also have a low GI. Here is the GI & glycemic load (GL) for various sweeteners:

| Glycemic index | Glycemic load | |

|---|---|---|

| Pure glucose | 100 | 10 |

| HFCS | 65 | 7 |

| Table sugar | 65 | 7 |

| Honey | 61 | 12 |

| Agave | 13 | 2 |

Most of the time, a low GI is regarded as healthy — and it usually is when we talk about stuff like collards and black beans. Foods high in fibre, fat, and protein, and whose carbohydrates are complex, digest slowly. They don’t convert quickly to glucose, so their GI is low.

Why do many people argue that “natural” sweeteners like honey and agave, or dried fruits such as dates, are “healthier” and/or “good” for people like diabetics?

This preference is actually a misconception about what the GI index means and how it works.

Agave does have a very low glycemic index (GI). However, the reason that agave has a low GI is because of its extremely high fructose content. Fructose has a low GI because nearly all of it is immediately soaked up by the liver without stimulating insulin secretion.

Once in the liver, fructose restores liver glycogen and then enters pathways that provide compounds for fat production. Any fructose that isn’t needed for liver glycogen will spill over into the blood as fat.

So, high amounts of fructose flooding the liver will favor the production of fat.

This is likely why diets with a lot of fructose (more than 50 grams per day) are associated with high blood triglycerides, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Fructose can also influence fullness cues. See All About Fructose for more.

Fructose and its discontents

Quantity

Some experts hypothesize that chronically consuming more than 50 grams of fructose per day will elicit type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. And it gets worse the more we consume.

On the other hand, consuming less than 50 grams per day seems to result in no negative health effects.

To hit 50 grams of fructose, we’d need to consume either 100 grams of table sugar, 91 grams of HFCS, or 60 grams of agave.

In the case of sweeteners, that’s about 400 calories of straight sweetener. I think we’d all agree that 400 calories of sweetener each day is setting someone up for Operation Obesity. If you eat 2000 calories per day, 400 calories is almost 25% of your diet.

Making it real: Sweeteners in daily life

Now, let’s translate 50 grams of fructose to real foods and drinks.

- A 32 fl ounce soda sweetened with HFCS has about 50 grams of fructose.

- A 32 fl ounce soda sweetened with agave has about 56 grams of fructose.

Either way, it’s not difficult to rack up sugar grams when you use sweeteners.

However, with whole, unprocessed foods, it’s a lot tougher. For instance, you’d have to eat about 10 apples… or an unimaginably intestinally distressing quantity of red beets.

With processed foods, even ones that aren’t obviously sources of sweetener (e.g. soft drinks), it’s still easy to get way too much sugar.

Let’s get into the real world with some examples. Say someone eats the following:

| Meal | Foods eaten | Sugar content |

|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Honey Nut Cheerios with sweetened soy milk Glass of orange juice |

45 g |

| Snack 1 | Nutrition bar | 25 g |

| Snack 2 | Can of Slim-Fast | 34 g |

| Dessert | Bowl of low-fat ice cream or frozen yogurt | 30 g |

That’s 134 grams of sugar, and if most of that is table sugar, then about 65 grams of it is fructose. And that’s definitely not a crazy day of eating in North America. Some people might even consider it healthy.

So, lots of refined fructose can be disastrous to our health. And with a name like HFCS — the stuff must be loaded.

Agave = health food? Not.

Based on the “excessive fructose can kill us” theory, agave and honey would be worse than HFCS-50 or HFCS-42 (HFCS-90 is generally not used in food products, but rather to make HFCS-50 and -42).

I have clients who won’t come within 10 feet of HFCS but will eat 3 servings of a dessert loaded with agave or honey.

Is this better for the health of the planet? Probably.

Is this better for the health of their body? I doubt it. They’d probably be better off just eating one serving of whatever dessert they really enjoyed.

But wait, at least agave is loaded with antioxidants. Ummm, not really. The antioxidant content is actually minimal, similar to corn syrup and refined sugar.

Considering all the costs

When comparing sweeteners, it seems that quantity is the most critical factor influencing our health and body composition.

I mean, you may get some additional antioxidants with molasses, maple syrup, date sugar, and/or honey. But then again, if your main dietary antioxidant source is a sweetener, you might need to set up a consultation with me, stat.

Economic and environmental impact of sweeteners

Beyond health, what sweetener is better for the planet? Probably agave or honey since they are the least processed and don’t require many harsh chemicals.

Supporting HFCS supports corn subsidies. This feeds into the larger system of poor farm and agricultural management. Further, getting HFCS from corn is costly, from an environmental perspective.

Why is HFCS even used? Mainly money. It’s cheap due to corn subsidies and the cost of sugar imports.

And let’s be honest, there’s a high correlation (based on my ventures to the grocery store) between products containing HFCS and food companies that don’t care about our health/planet. If a food has HFCS, it’s probably a crappy food to be consuming regularly on both fronts.

Slave sugar

Cheap or enslaved labour in Caribbean, South American, and South Asian colonies ensured that starting in the 1500s, sugar was more available to the average consumer; before then, it had been a luxury item restricted to the upper classes.

Sugar is still produced under poor labour conditions in most places. Most sugar comes from developing nations. Workers are not always sufficiently compensated for their efforts nor treated humanely.

Fair trade certification means the workers are getting a fair wage and fair treatment. Is your sweetener Fair Trade Certified?

Summary and recommendations

No matter which sweetener you choose, quantity is the real issue.

If sweeteners — from any source — make up more than 5% of your overall diet, that’s probably bad news for your heart, vessels, waistline and insulin sensitivity.

Let’s say you consume about 2000 calories per day. 5% of that is 100 calories per day. Translation: 25 grams or about 2 tablespoons of added sweeteners.

Further, when food/drink taste really sweet, appetite regulation goes knucklehead and we tend to consume more than we need.

Sprinkling some date sugar on your oats, drizzling agave in your green tea, or eating a piece of pumpkin pie on Thanksgiving are probably fine. Beyond that, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

From an environmental perspective, unprocessed sweeteners like agave and honey seem to be the better options.

Extra credit

Some HFCS has been shown to be contaminated with mercury.

Sugar can be fermented into alcoholic beverages. The blue agave plant produces a liquid that can be fermented into tequila. Honey can be fermented into mead. Molasses can be made into rum. Canadians have yet to figure out maple syrup booze, though.

In 1984, Pepsi and Coke made the switch from refined sugar to HFCS in their beverages. That’s the same year the first Apple Macintosh went on sale.

Molasses is a byproduct of sugar processing, to which sulfur is usually added as a preservative. It was the sweetener of choice in the US until late in the 19th century. In 1919, a huge vat of molasses at a distillery in Boston exploded. The enusing “Great Molasses Flood” killed 21 people and dumped two million gallons of molasses into the streets.

Honey has antibacterial properties. People used it traditionally to prevent infections from wounds, and Manuka honey in particular is effective against antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as MRSA. (Maybe we should be putting honey on our bodies instead of into our bodies.)

Honey takes on different flavours depending what the bees have eaten.

Birch syrup (which uses the sap from the birch tree) is also popular in regions such as Scandinavia and northern Canada.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Learn more

Want to get in the best shape of your life, and stay that way for good? Check out the following 5-day body transformation courses.

The best part? They're totally free.

To check out the free courses, just click one of the links below.

Share