Many of you have heard that stress triggers your body to release cortisol, and that cortisol gives you your beer belly. Maybe that explains Santa Claus’ rotund physique.

After all, if you had to meet the demands of hundreds of millions of children, deal with elvish labor issues, and wrangle several wild beasts in your annual commute, you’d probably be stressed out too.

So what should you and Santa do? How do you get rid of the stress? Should you quit your job, leave Mrs. Claus, sell your kids, elves and reindeer? Move to an island paradise? (Who knows — maybe Santa is detoxing in the Caribbean right now.)

The island paradise could work… until the next hurricane. Then you’d be stressed out, squirting cortisol into your veins, and trading your compact spare tire in for a tracker-sized spare tire. It seems that most of us can’t avoid experiencing at least a little stress, regardless of whether we’re at the North Pole or the equator.

If you can’t stop stress, then do the next best thing: stop the stress response by suppressing cortisol levels. Cortisol is a hormone secreted by the adrenal glands (which sit on top of the kidneys) in response to stress. One of cortisol’s actions is to weaken the immune system, but it can also raise circulating glucose levels and inhibit bone resorption as well as protein and collagen synthesis. We need cortisol, but too much for too long can do some nasty stuff.

Research question

In the last few years, a supplement called phosphatidylserine has been promoted as a cortisol suppressor that reduces abdominal fat. To give credit where credit is due, Charles Poliquin was one of the first to promote phosphatidylserine in his Biosignature course to specifically target “umbilical” fat, or fat around your belly button.

But first things first. Before we get too far ahead of ourselves we need to know whether phosphatidylserine actually suppresses cortisol in a stressful situation, such as exercise. Which brings me to this week’s research review…

Starks, Michael, et al. The effect of phosphatidylserine on endocrine response to moderate intensity exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 5, no. 11 (2008).

Methods

Participants

The study sample was relatively small: ten young healthy males, who were:

• 26 ± 1.5 years old

• 89.3 ± 4.7 kg (about 195 lbs on average)

• 176.8 ± 2.7 cm (about 5’8″ on average)

Like many studies that look at supplements in a non-disease state, the subjects of this study were university age -– most likely graduate students. Why? Easy recruitment.

You see, the studies are usually run by graduate students and they ask their fellow graduate students to take part in their study. In return, the researchers will participate in the other grad students’ studies. This means that pretty much the same group is in all the studies from that department in that time period. Needless to say, the results may not be universally applicable.

Testing

Step 1: Establish a baseline

Before the researchers started the phosphatidylserine supplementation, they tested all the participants for their maximum ability to use oxygen, or VO2 max, with a bike. This is a very common test that uses either a bike or a treadmill and a gas collection apparatus to measure how much oxygen participants consume. In the beginning, the given exercise is easy and progressively gets more and more difficult until subjects can’t continue. Then researchers analyze the data and figure out the maximum amount of oxygen used. The exact number isn’t important for the study, but rather a tool to figure out the appropriate level for exercise testing. In a way it’s similar to a one repetition maximum in strength training.

For those who are interested, the average VO2 max for the participants was 29.0±2.2 ml/kg/min -– not impressive at all. (Looks like this particular group of grad students was more brains than brawn.)

As an aside, many believe it’s this VO2 max test that has led to so much more research done on aerobic exercise than resistance exercise. VO2 max can’t be influenced by how much you want it or how motivated you are. With the testing you can tell if someone hasn’t pushed themselves hard enough, while with resistance exercise you can’t.

Step 2: First round of phosphatidylserine to group 1

Once researchers figured out a starting VO2 max, they gave participants either 600 mg of soy-based phosphatidylserine or a maltodextrin placebo for 10 days and then tested their VO2 max again.

Step 3: Second round of phosphatidylserine to group 2

After the first round of testing the participants that were on the phosphatidylserine were given placebo and retested after 10 days, while the first group given placebo were given phosphatidylserine.

This is a “cross-over” design –- all participants get all treatments. Half get the placebo and half get the treatment first; then they “cross-over” and get the other treatment.

Another aside: originally phosphatidylserine was extracted from cow brains (bovine cortex),1 but since the health concerns with consuming neural tissue — because of mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE) — the industry has switched to soy-derived phosphatidylserine. With bovine cortex-derived phosphatidylserine, there was a lot of speculation that it wasn’t phosphatidylserine but rather the contaminating neural proteins that were suppressing cortisol. Since then, the study of soy-derived phosphatidylserine has proven that phosphatidylserine is effective at inhibiting cortisol.

Step 4: Re-test VO2 max

After the 10 days of supplementation, the participants biked for 15 minutes, starting at 65% of their maximum VO2 max, up to 85% VO2 max. This is considered moderate intensity, but enough to elicit an increase in cortisol. Blood samples were taken 30 minutes and right before exercise as well as right after, 5, 15, 25, 45 and 65 minutes after exercise.

Turns out that cortisol levels were lower in the phosphatidylserine group throughout (before and after exercise) and the peak was blunted in the phosphatidylserine group.

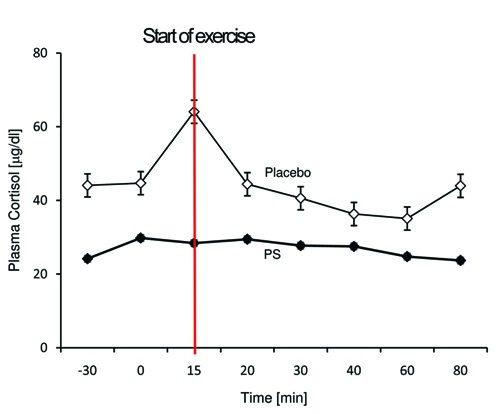

A picture is worth a thousand words, so below is the graph of cortisol blood levels in the two conditions. As you can see, the placebo group has higher cortisol levels throughout, with the biggest difference happening right after exercise. Mathematical calculations of the area under the curve show that supplementing with phosphatidylserine lead to 35% less cortisol. Peak cortisol levels were 39% lower than placebo.

Researchers also measured subjects’ testosterone levels. And surprise, when “area under the curve” was compared, the phosphatidylserine group had higher testosterone levels.

They also looked at lactate and growth hormone, but found no difference.

Conclusion

Phosphatidylserine (600 mg) per day for 10 days reduces exercise-induced cortisol levels.

Oh, you want more. Okay.

Based on this study phosphatidylserine supplementation can be used to reduce exercise-induced stress caused by cortisol. So what does that mean? The authors suggest that phosphatidylserine could be a treatment for over-training.

While this study finds that testosterone is higher in the phosphatidylserine group I’d wait until a few more studies come out with the same finding. There have been other studies showing a decrease in cortisol with phosphatidylserine but no change in testosterone.2

Here’s one other important finding: dosage. Past experiments used 800 mg of phosphatidylserine, while this study used 600 mg.2 Turns out that 600 mg is an effective dosage to inhibit cortisol and since phosphatidylserine is a bit pricey, you can save yourself 25%. Santa will have enough money to stock up at the Boxing Day sales.

Eat, move, and live… better.©

The health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn’t have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies — unique and personal — for you.

Click here to download the special report, for free.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Share