If one natural food source were to earn the title of “controversial food of the year” it’d likely be soy. That’s why we wrote this article. Hopefully it helps you sort through the big soy protein controversy, leaving you with some practical strategies for soy consumption.

Why was soy promoted as a nutritional wonder by the ADA and AMA only to fall from grace, stimulating radical, and often diametrically opposed opinions from experts and nutrition buffs across the globe?

Why have recreational exercisers and internet posters on nutrition sites, vegetarian sites, fitness sites, bodybuilding sites, and health/wellness sites begun to either champion soy or denigrate its value as a viable food option?

And finally, with all the hullabaloo, all the back and forth, all the controversy, why aren’t people capable of having an objective discussion of the value soy may or may not have in the diet.

Well, these are all questions we’ve been wondering about. So we turned to the research. We interviewed a host of soy experts on both sides of the fence.

And from our research, we wrote this article. Hopefully it helps you sort through the big soy protein controversy, leaving you with some practical strategies for soy consumption.

A brief history of soy

Some of the first crops grown – way back in the 11th century BC – were soybean crops. These beans are native to East Asia and it’s no surprise that Asian cultures are known as innovators when it comes to soy products.

The three most important food derived from soy are things that are fairly common nowadays like miso, tofu, and tempeh. Interestingly, these foods have long been considered both nutrition and medicine in East Asia.

It wasn’t until the early 1700’s that soy was introduced in Europe. Shortly thereafter, in 1765, the first soybean plant was grown in North America.

Soy was initially grown in North American to feed animals. It didn’t become a human food crop until the early 1900’s. My, how times have changed. Today, 55% of total soy production originates in the United States.

However, the soy appearing today ain’t your grandmother’s soy crop. Genetically modified soybeans were introduced in 1995 – these modifications being made made to reinforce the crop against pests as well as against the chemicals farmers spray on the crop to prevent weed growth (think Round-Up).

Interestingly, about 13 years later, about 90% of the soybeans produced are genetically modified in one way or another.

What’s in a soy bean?

In terms of protein content, the soybean is roughly 41% protein. And the PDCAA score (a measure of protein quality) for soybeans is just below 1.0, with soy protein isolate at 1.0. As 1.0 is the highest score a protein can get, soy ranks right up there with milk, beef, and egg proteins.

When breaking down the specific amino acids, soy is rich in branched chain amino acids, lysine and arginine while being low in methionine and cysteine. To this end, soy protein is still “complete” in terms of the full amino acid profile.

However, due to the lower methionine and cysteine content, it’s marginal in this regard. Indeed, some experts consider soy a touch inferior to animal-based proteins.

In terms of dietary fat, the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fat in soybeans is about 1:7, which is sensible, especially when compared to oils like sunflower and peanut which are 1:100+.

Finally, soybeans contain a mix of slow-digesting carbohydrates. With fiber and other starches that may be good for promoting the growth of healthy bacteria in the gut, soy could be considered GI-friendly (assuming no soy maldigestion or allergy).

Is anyone actually eating soy?

Contrary to popular belief, cultural observation tells us that most traditional cuisines – even Asian cuisines – don’t incorporate soy as a staple food. The average soy intake in East Asian populations is between 40 – 90 grams per day (1.5 to 3 ounces).

Folks, that’s TOTAL soy intake (not soy protein grams). Indeed, this amount of soy equates to roughly 10 – 20 grams of soy protein per day.

In these cultures, soy is generally used as an occasional meat replacement or as a condiment to the main dish. In China, tofu has been nicknamed “the meat without bones,” because of its versatility in creating so many “meat like” replacement products.

In North America, unfortunately, refined soy foods – things like soy concentrates, textured soy, soy lecithin, etc. – are finding their way into more foods on supermarket shelves. Also unfortunate is that they’re becoming what people equate with soy consumption.

Indeed, between 2000 and 2007, United States food manufacturers introduced over 2,700 new foods with soy as an ingredient. And most of the soy foods being sold in North American are heavily processed.

The whole soy story

Kaayla T. Daniel, PhD, wrote a very controversial book all about soy. Her book, and related interviews, has introduced popular culture to a host of valid points about the potential dangers of excessive soy intake.

Unfortunately, rather than understanding the context, after reading one of her books or interviews, most folks will take a big step back from soy based foods.

However, even Dr Daniel has been very clear to note that a soy food intake similar to that of Asian cultures is healthy and doesn’t pose dangers.

We caught up with Dr Daniel recently, and this is what she said:

“Asia is a huge continent with many different dietary patterns and lifestyles. However, soy is always eaten in small quantities as a condiment in the diet and not as a staple food.

For most people, I do recommend soy foods made with organic soybean. But it’s important for people to understand that all soybeans, organic and otherwise contain phytoestrogens and anti-nutrients.

Thus, people put themselves at risk for health problems if they consume soy milk, veggie burgers and other unfermented soy products whether or not they buy organic.

Daniel has also stated that old fashioned soy products such as miso, tempeh, natto and soy sauce are fine when eaten occasionally. In fact, Daniel even confided in us personally that she and her children include them in their diets.

These products are encouraged by Daniel because they’re fermented. And the fermentation process in these soy foods can deactivate specific anti-nutrients – nutrients that cause digestive distress and mineral loss.

The day I contacted Dr. Daniel, she had just finished filing a petition with the FDA asking them to retract the soy/heart health claim. See here.

Another expert many of you may know, Cassandra Forsythe, PhD, author of the Perfect Body Diet, recently shared her thoughts as well.

Although she used to have the belief that soy, and all soy-related products, were detrimental to health and the achievement of an ideal body composition, she’s revised her position. S

he now feels that occasional soy protein consumption may not have such effects. Forsythe has also indicated that manufactured soy protein may have different effects than traditional soy foods, such as whole bean edamame.

But doesn’t soy decrease testosterone?

At this point, I want to dig into some interesting research. Specifically, let’s take a look at a 3-month study looking at the effects of different protein types on body composition during a strength training program.

In this study, the researchers provided daily supplements containing 50 grams of a variety of proteins – either soy concentrate, soy isolate, a soy isolate/whey blend, or a whey blend.

20 participants added these supplements, in conjunction with a resistance training program.

At the end of the 3 months, a significant increase in muscle mass was noticed with all of the protein supplemented groups. Interestingly, no significant differences were found among testosterone, body fat or body weight between the groups.

In the end, the authors concluded that 12 weeks of soy protein supplementation (50 grams per day) was as effective as the other protein types when it comes to boosting muscle mass during a strength training program.

Interestingly, as some people have suggested, soy supplementation doesn’t seem to decrease testosterone or limit lean body mass gains. It’s important to note that similar studies have been done using soy-containing supplemental nutrition bars. And the results have been consistent.

In another study using rats and endurance exercise, the authors concluded that protein synthesis was comparable between rats fed different protein-containing meals after exercise – including soy.

In yet another study, researchers found that elite gymnasts supplementing with soy protein (1 g/kg) for 4 months, saw favorable changes in their stress responses to training (when compared to the gymnasts not using any supplemental protein at all).

Finally, a Romanian study using Olympic athletes supplemented participants with soy protein (1.5 g/kg) for 8 weeks.

In the end, the authors found that the soy protein supplementation led to increased body mass (~ 3 kg, mostly from lean body mass) and strength indexes. Significant decreases of fatigue were found after training sessions.

No negative side effects or abnormal changes to metabolism were noticed and the product was well tolerated.

Now, before we move on, we want to be clear about one major, important thing. This section isn’t designed to promote soy protein supplementation. Not in the least.

However, it is here to demonstrate that when used as part of a sensible training program and varied, calorie sufficient diet, soy protein supplementation acts much in the same way that other protein supplements might act – with increases in lean body mass, decreases in stress hormone responses to training, and improvements in performance.

What about those soy phytoestrogens?

Many exercisers and athletes are concerned that the phytoestrogens (estrogen-like nutrients – things like isoflavones) in soy might be harmful to their health, hormonal profile, and body composition.

Well, before discussing this very “applied” issue, let’s look at what phytoestrogens really are…

Phytoestrogens (we’ll call them “PEs” from now on) are a group of natural estrogen receptor modulators found in various foods, with soy being the predominant source. These PEs serve as a defense mechanism in plants and as a natural fungicide.

When soy protein isolates and concentrates are created from soybeans, PE (and phytonutrient) content is diminished due to the alcohol used in extraction. So many of the PEs are naturally removed during the extraction process. However, some do remain.

The PEs found in soy foods include: genistein, daidzein and glycitein. These PEs are similar in structure to the estrogen hormone – estradiol. As a result, PEs have both weak estrogen-stimulating (estrogenic) and an estrogen-inhibiting (anti-estrogenic) effects, depending on the circumstance.

When someone swallows a mouthful of soy, the PEs are modified by intestinal bacteria and taken up into the blood. Once in the blood, these chemicals can weakly bind to the body’s estrogen receptors.

The body recognizes this binding of its estrogen receptors as a signal to produce less of its own estrogen. Now that’s one way that soy can actually lower estrogen production.

Another potential mechanism of PE action in the body is the alteration of circulating estrogen and testosterone concentrations. These can be altered by the PEs binding to sex-hormone binding proteins found in the blood.

The UK Committee on Toxicity (2003) noted that PEs bind weakly to the sex-hormone binding proteins and are unlikely to prevent estrogen or androgen binding (at normal blood levels).

However, when consumed in high doses, PEs could potentially act as anti-estrogens at the cellular level (by competitively binding to estrogen receptors), thus preventing the binding of estrogens that were produced within the body.

However, by binding to sex-hormone binding proteins, these PEs could displace estrogens from their blood-bound carriers and free them up to provoke stronger estrogen action in the body.

So, as usual when it comes to biochemistry, there’s no clear cut explanation for determining how PEs will function in the body. The actual effects depend on total amount of PEs in the body, receptor binding affinities, and probably a host of genetic factors.

Ok, now that we have some idea (a murky one, at that) of how PEs work in the body, let’s look at what the research says regarding how PEs might affect our hormonal action.

One study demonstrated that rats with a high exposure to PEs from soy (20 mg/kg and greater) had lower testosterone levels. Now, here’s the important differentiation point. In the lower dose groups, there were no significant changes to testosterone. (More on this below.)

Further, other studies are mixed – showing no change in testosterone levels, lower testosterone levels, or with a down regulation of estrogen receptors with high PEs in the blood.

So, in the end, despite these mixed results and a lack of consensus, there is a common theme: extremely high levels of PEs have an unfavorable influence on hormone levels, especially when it comes to hormonal status as well as building muscle and staying lean.

From rat to real life

Before we go on, let’s do something very important – something many authors fail to do. Let’s put these rat studies into a real life perspective.

We’ll start by looking at an adult male who weighs 190 lbs. (86 kg). If he were to consume 20 mg/kg of PE (like the initial rat study indicated), that would be 86kg * 20mg. And that would mean 1720 mg of PE per day.

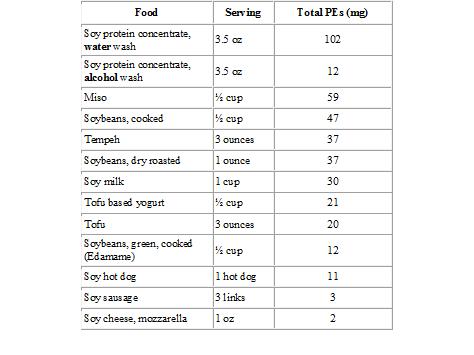

Do you have any idea how much soy that’d be?!? If not, check out the following table. It gives you an idea of how much PEs are found in soy foods.

Now, as you can see from the table, our hypothetical male is VERY, VERY unlikely to consume 1720 mg of PE from food. Check out the following menu:

Now, as you can see from the table, our hypothetical male is VERY, VERY unlikely to consume 1720 mg of PE from food. Check out the following menu:

- 1 cup of cooked soybeans = 94 mg

- 6 ounces of tempeh = 74 mg

- 2 cups of soy milk = 60 mg

- 6 ounces of tofu = 40 mg

- 2 soy hot dogs = 22 mg

- 4 oz of soy cheese = 8 mg

- Total = 298 mg

Soy overload, for sure, right? Yet it only supplies 289mg of PEs…one-fifth of what might be required to lower testosterone levels.

So let’s get real here…it’s unlikely that testosterone problems would occur if someone were to eat a moderate amount of whole food soy products.

Indeed, a more traditional daily intake of soy for someone may look more like this:

- 8 ounces of tofu = 53 mg

- ½ cup soy milk = 15 mg

- ½ cup edamame = 12 mg

- Total = 80 mg of PEs

No more rats: Humans and phytoestrogens

Taking it to human studies, data on patients with prostate cancer showed that the intake of 80 mg/day of PEs did not significantly alter testosterone levels.

To go one step further, an intake of PE up to 16 mg/kg of body weight had no significant influence on behavior or physical characteristics.

Taking the dose up again, another study found that 84 straight days of consuming 450 – 900 mg/day of PE lowered DHEA levels and had estrogenic side effects in males with prostate cancer. Not necessarily good.

However, skim over the chart above to determine how much soy food that would be – it’d be a freakin’ lot!

Revisiting our idea from earlier, the fact that Asian cultures aren’t eating tons of soy foods, dietary PE intake has been reported to be about 65 mg/day in some Asian populations, with the Japanese averaging about 45 mg/day.

So the conclusion seems pretty simple…small amounts of PEs are probably fine. And small amounts are likely all you’ll get with a normal, occasional whole-food soy intake.

Soy and sperm

Have you ever heard of Dr. Jorge Chavarro? He and his colleagues from Harvard revealed findings from a study that show soy-derived foods and PEs linked to lower sperm concentrations. Not good, right.

However, the research did not find a negative relationship between soy and sperm mobility or sperm quality, which are both key factors to fertility. So maybe it’s not that big of a deal after all.

For this study, the researchers surveyed men on their consumption of 15 soy-based foods during the last 3 months and did not directly determine what other foods, medications, supplements, existing medical conditions, sexual activities or environmental factors may have affected the drop in sperm count.

Many of the study participants were overweight or obese, and males with high levels of body fat produce more estrogen than their lean counterparts. So, in this study, whether it was soy that caused the drop in sperm count or something else is hard to say.

Indeed, Asian populations have regularly consumed soy for generations without fertility disorders.

Also, Asian countries have healthy, high functioning children. Dr. Chavarro revealed that East Asian men consume more soy than the participants in his trial and do not develop fertility problems. Maybe genetics…maybe something else entirely.

Of course, this research aside, there is a body of research in which controlled amounts of PEs were fed to humans or primates and no negative effects on quantity, quality, or sperm motility were noticed.

Other concerns for hormonal manipulation via diet

With all of the concern and attention being devoted to soy intake and hormonal changes, we always remind ourselves that there are other dietary factors that can have an unfavorable impact on hormone levels.

Chronic alcohol intake is one of the most powerful mediators of sex hormone levels. Ethanol is a testicular toxin.

Chronic male alcoholics develop an assortment of endocrine disorders, including infertility, testicular shrinkage, and feminization, caused in part by elevated production of estrogens and inhibition of testosterone biosynthesis in the testis.

Also, alcohol increases the activity of aromatase, an enzyme that converts testosterone to estrogen in the body.

Also…estrogen. The major source of animal-derived estrogen in the human diet is milk and dairy foods.

60-80% of the dietary intake of estrogens originates from milk and other dairy foods in the Western world. In a Western diet, milk is produced predominantly by lactating cattle and gestation is under the control of steroid hormones, including estrogens.

Thus, high levels of milk-borne estrogens can be expected.

The milk that we now consume is quite unlike that which was consumed 100 years ago. Authors have hypothesized that milk is responsible, at least in part, for some male reproductive disorders.

Other authors have stated that “The Western diet (characterized by milk/dairy products and meat) causes a trend of increasing levels of estrogen.”

Maternal beef consumption (specifically, beef containing hormones) may also alter a man’s testicular development in utero and adverse affect his reproductive capacity. The point?

Well, it’s odd that soy is getting hammered for hormonal implications when, indeed, many of our dietary staples (alcohol, milk, and meat) all might also have an impact on our hormonal levels if we’re not conscientious about ensuring adequate exercise and a varied diet.

Rapid-fire: Soy and other health conditions

Soy and bones

Soy and other plant proteins have a lower net acid excretion, but it still isn’t clear if they have skeletal advantages over animal proteins.

A recent trial in North America looked at the effects of taking soy protein and doing moderate exercise on bone health in post-menopausal women.

43 post-menopausal women completed the trial. They were given either milk protein or soy protein isolate powder (both including calcium and vitamin D), with or without a supervised moderate exercise program (3 x/wk) for 9 months.

Compared with milk powder placebo, women on soy powder had significant reductions in bone turnover, but not in bone mineral density. High bone turnover leads to a greater propensity for fracture.

Two new meta-analyses from China have looked at the effect of PEs on bones. In the first meta-analysis, data from 10 trials involving 608 menopausal women showed a significant benefit on spine bone mineral density, this was predominantly noticed when PEs were given in higher doses and for longer periods.

In the second meta-analysis, data was combined from 9 trials on 432 subjects and showed that PE significantly increased bone formation and decreased bone resorption.

Soy and body composition

We know that protein is more satiating than carbohydrates and fat, and higher protein diets seem to be important for a healthy body composition, and soy protein seems to be as effective as other proteins in this regard.

An evidence-based review by Drs. Allison and Cope (Univ of Alabama at Birmingham), and Dr. Erdman (Univ of Illinois at Champagne-Urbana), found soy foods equal to other protein sources, such as dairy or meat, in helping to promote fat loss.

The review was published in the November 2007 issue of Obesity Reviews. The review found that individuals lost equivalent amounts of weight (and inches in some cases), using soy protein, dairy milk meal replacements, and beef or pork at equal calorie levels.

Soy and anti-nutrients

Trypsin inhibitors? Phytic acid? No, these are not characters from the new Shrek movie. These are substances found in soy foods. The good news is that they are deactivated by cooking and fermentation.

So consumed cooked and fermented soy foods won’t inhibit protein and mineral absorption. Also, phytic acid may have anti-cancer properties.

Soy and the heart

The American Heart Association (AHA) gives the “bottom line” about soy on their website:

“Taking soy or isoflavone supplements is unlikely to reduce your risk of heart disease. Eating foods that contain soy protein to replace food high in animal fats may prove beneficial to heart health.”

Now, I don’t place much weight on the opinion of the AHA. Why? Well, take a look at the following: you have to look close, but this side of this box of Nutri-Grain Yogurt Bars, we’ve got the AHA stamp of approval.

Ever since this was brought to my attention, conclusions made by the AHA mean about as much to me as my mom’s dog taking a crap in the park. I know, crude. But seriously, AHA. Nutri-Grain yogurt bars? Phhulleeze….How can we believe anything you say now?

Plant protein and kidneys

Soy protein, despite being of very high quality, doesn’t appear to have the same effect on kidney function that occurs in response to animal proteins. So, if your doc, or your mom still gets worried about the high protein meals, mix in some soy for good measure.

Soy recommendations and conclusions

Based on all of our readings, discussions and knowledge acquired about soy foods over the past 10 years, it seems that a reasonable amount of unrefined soy intake is fine.

Now, we don’t think soy is anything special in terms of disease prevention. Nor do we think it’s extremely harmful in your quest for optimal health, body comp, or performance.

With that said, we do caution against excessive soy intake. When consumption of soy foods is excessive, there might be some negative effects going on.

To this end, it seems best to avoid isolated and highly refined forms of soy on a regular basis. In other words, things like soy isolates, soy concentrates, textured soy protein, etc should be minimized in the diet.

Whole soybeans, soy milks, tofu, tempeh, and miso, on the other hand, are better options.

In terms of total intake, we’d say 1-2 servings of soy per day seems to be a safe and potentially healthy intake, but exceeding three servings per day on a regular basis may not be a good idea. (A serving is 1 cup of soy milk and 4 ounces of tofu/tempeh/soybeans.)

Now, it’s easy to understand how some individuals can consume excessive amounts of soy. Soy milk on the morning cereal, a soy protein smoothie for a snack, a soy burger at lunch, soy pretzels as a snack, and soy ice cream for dessert.

Even a soy novice would recognize that to be soy overload. So don’t make the mistake of eating tons of soy – even if you’re on a plant based diet.

Watch out for food pushers

While excessive soy consumption gets a bad rap, we often think about the excessive consumption of any one food and the potential negative effects. As we presented in this article, what about the high intake of alcohol? Or factory farmed dairy and meat?

Soy is a chief ingredient in the feed of factory farmed animals. Does this indirectly influence the nutrition of meat-eaters? Should they only purchase grass-fed animals? We hesitate to think that any “mono-food” excess is a good idea on a regular basis.

And, of course, the soy industry does it’s part (just like the dairy, egg and beef food pushing industries) to create just that – a mono-food culture. They push soy by overstating the benefits and undermining the concerns.

You might be shocked to know that as a registered dietitian, I receive AT LEAST one mailing per week from a major food industry telling me to push their particular food on my clients. I’m not making this stuff up, folks.

Now, of course, these messages get the “delete” treatment just as fast as do those annoying penis enlargement emails that also seem to make it through the spam filters.

Just think

In the end, as JB and I often have discussed, there’s a simple rule of thumb that most people somehow forget…repeatedly. And it’s this: You don’t often go wrong with whole, unprocessed foods. Where the problems typically occur is with processed food, in all forms.

This rule of thumb is also true with soy. Whole, unprocessed soy, is just a food. It’s not a political agenda. It’s not a public health crisis. It’s not a way of life. It’s not a medicine. And it’s not a panacea.

It’s one food – one of a few thousand foods people can include in their diets…or not. It’s nothing more. So, as the title of this article hints at, we want people to re-freakin’-lax when it comes to soy. Moderate doses of whole-food soy proteins really are no big deal.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Learn more

Want to get in the best shape of your life, and stay that way for good? Check out the following 5-day body transformation courses.

The best part? They're totally free.

To check out the free courses, just click one of the links below.

Share