What is sodium?

We usually refer to “sodium” and “salt” interchangeably, but we shouldn’t. Sodium is merely a component of salt.

Salt is composed of 40% sodium and 60% chloride. So, one teaspoon of salt (5,000 mg) provides about 2,300 mg of sodium.

Nearly 95% of the salt we ingest is absorbed in the GI tract.

Salt is located on the ground in dry salt beds, in the oceans, in underground springs, and in rocks.

Once we get it, we use salt for flavor, as a preservative, and to prevent unintended hip flexor stretches on icy driveways.

In the 1920s, scientists noticed that adding iodine to salt could prevent iodine deficiency. Both iodized and plain salt are available today.

Salt draws water out of food, eliminating the moisture needed for bacteria to thrive. This makes it a useful food preservative, a practice that has been recorded as far back as 2000 B.C.

Why is sodium so important?

If we don’t get a minimal amount of sodium, we die. Thus, it’s essential to obtain sodium from the diet. (Luckily a deficiency of sodium is not common.)

Once we consume sodium, the body also needs to regulate it tightly — again, if this is out of balance, we die.

Sodium and chloride are the main ions found in fluids outside of cells, including blood plasma.

When dissolved in fluids, sodium possesses a mild electrical charge (making it an electrolyte). The difference between ion concentrations across cell membranes creates a membrane potential, which is necessary for nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction and cardiac function.

Sodium is also required for fluid regulation, nutrient transport, blood pressure regulation, and expansion of blood volume that accompanies tissue growth.

How the sodium-potassium pump works (Animation)

Sodium and the modern diet

Some speculate that excess sodium in an industrialized Western diet accounts for a proportion of high blood pressure levels, strokes and heart attacks.

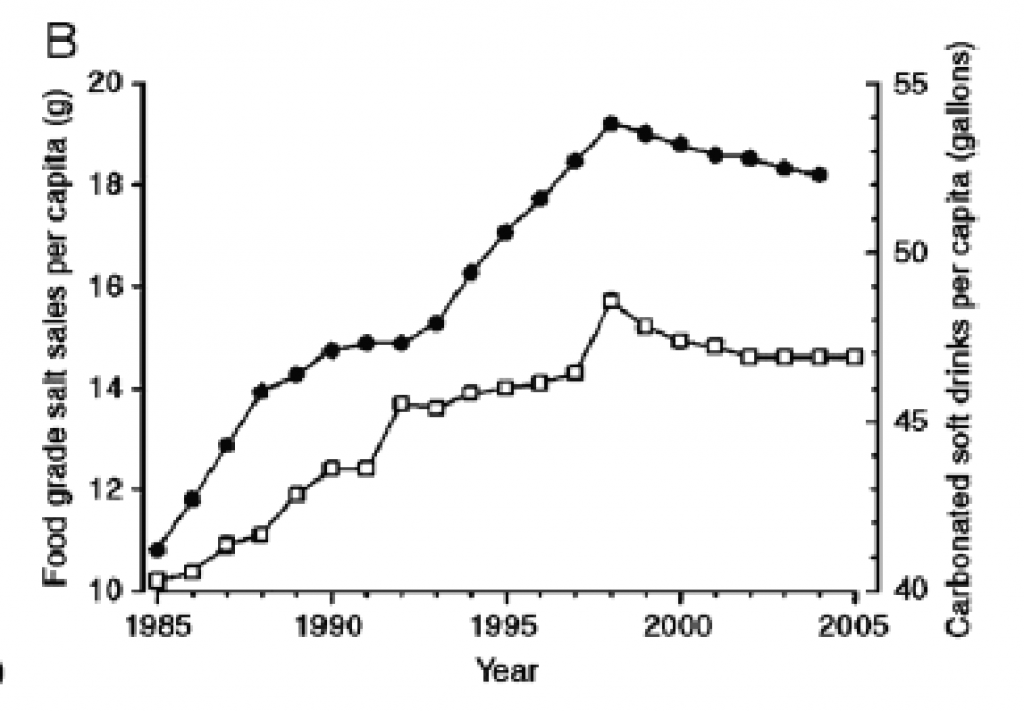

Despite this health risk, many foods with salt are continually produced since the revenue of beverage, food and salt companies is dependent upon salt consumption. This trend currently shows no sign of declining. In the year 2000, salt intake in the U.S. was remarkably higher than in the 1970s.

The average North American now consumes about 3,400 mg of sodium per day. Experts recommend that we consume less than 2,300 mg per day, and less than 1,500 if we’re in a higher-risk group (which the majority of Americans are).

We can survive on just 500 mg per day.

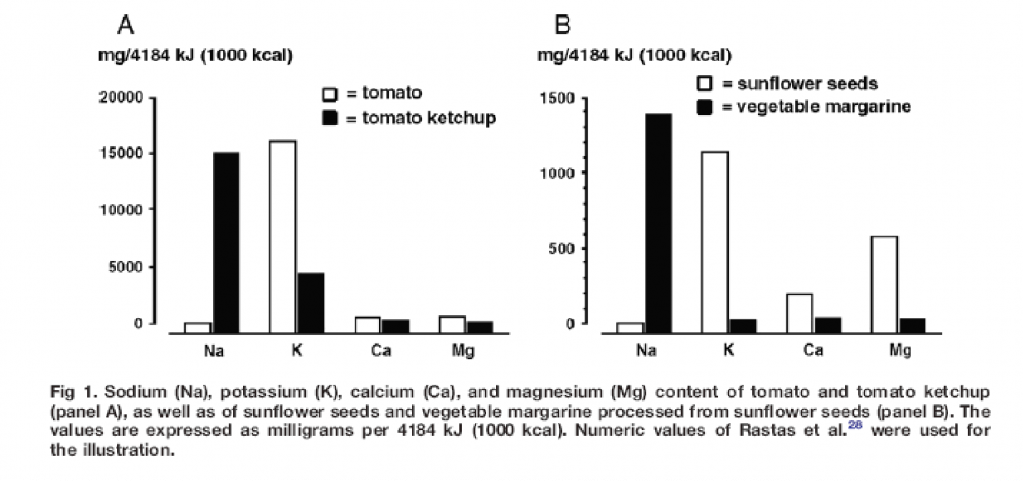

A daily food intake composed of 2/3 plant foods (unprocessed) and 1/3 animal foods (unprocessed) provides about 600 mg of sodium (when no other salt is added). A 100% plant-based diet generally provides closer to 300 mg of sodium.

It’s nearly impossible to consume more than 1200 mg of sodium per day from unprocessed foods.

The Denny’s Meat Lover’s Scramble consists of:

2 eggs with chopped bacon, diced ham, crumbled sausage and cheese

2 bacon strips

2 sausage links

hash browns

2 pancakes

= 5,690 mg of sodium (379% of the advised daily limit)

Thus most sodium in our diets now comes from processed foods, not the salt shaker.

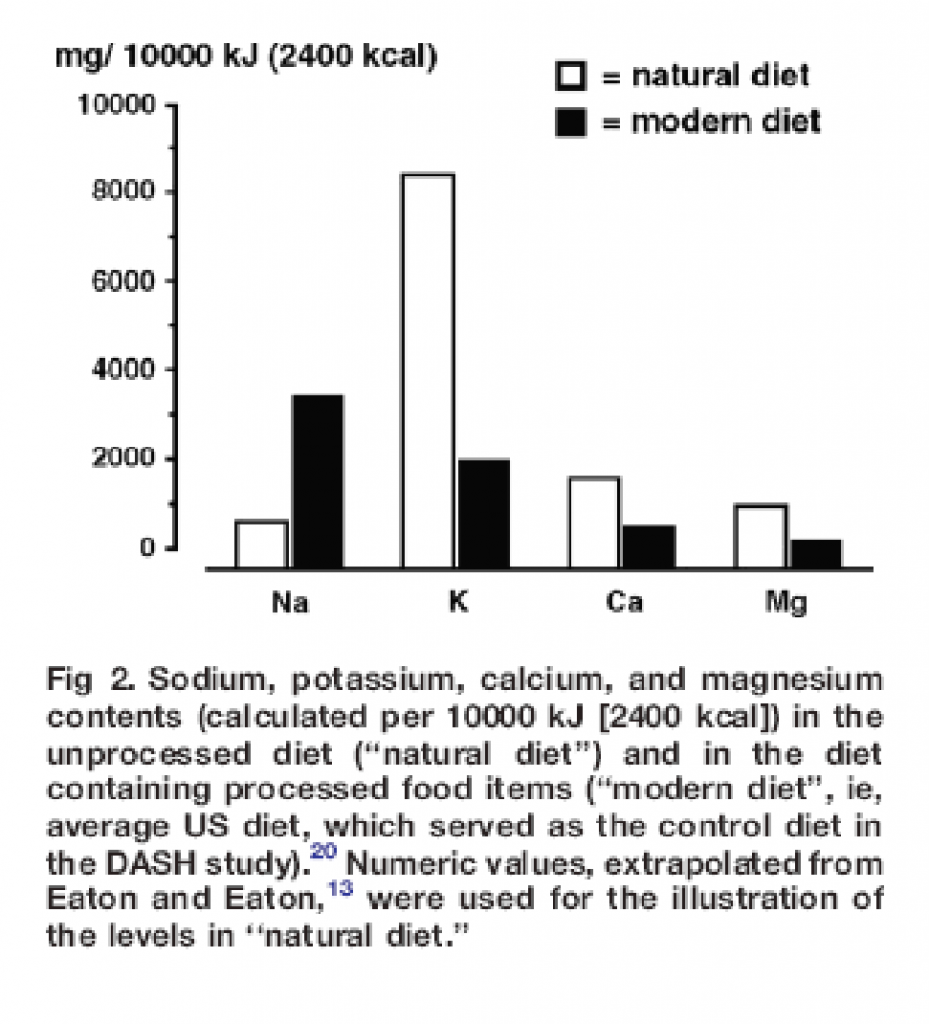

Compare the foods below: tomatoes vs tomato ketchup; sunflower seeds vs vegetable oil-based margarine.

Our body’s reaction to sodium

When we consume excess sodium, blood pressure increases in an effort to rid the body of excess sodium and fluid. The kidneys filter out the sodium we don’t need and we excrete it in urine.

When the kidneys aren’t functioning optimally, we accumulate sodium and fluid. This means swelling.

The effect of salt on the body (Animation)

High blood pressure

If we consistently consume lots of salt-laden food, blood pressure stays elevated. This means the heart and vessels must work harder. Extra pressure can weaken vessels and cause vessel injury, leading to atherosclerosis and kidney disease.

Reducing sodium intake to less than 2,400 mg per day can decrease blood pressure by up to 8 points. If plenty of mineral-rich plant foods are consumed as well, this might reduce pressure nearly 14 points more.

For someone who’s already been diagnosed with hypertension at 155/105, the 8 to 14 point deduction won’t make a huge difference. However, for a pre-hypertensive person (say, 130/80), a 14-point drop can move someone from “risky” to “pretty good”.

When you factor in regular exercise, a lean body, and minimal alcohol – blood pressure can drop by up to 47 points!

Can we really say salt is to blame for the countless cases of high blood pressure? I don’t know.

High blood pressure may instead be secondary to processed food intake (which have lots of salt), obesity, no exercise, high alcohol intake, low veggie/fruit intake, etc. Some experts theorize that refined carbohydrates play a major role in high blood pressure.

When we consume more plant foods with potassium, sodium excretion via the urine may increase. This may be the main reason behind a nutrient-rich diet regulating blood pressure, preserving bones and preventing kidney stones. And speaking of bone preservation, consuming excess sodium increases calcium loss in the urine.

American Heart Association: Assess your HBP risk

What you should know about sodium

Sodium intake as a survival mechanism

In animals that are herbivores, the desire for sodium increases in the spring and summer. Why? Because plants consumed in the warmer months are high in potassium and water, driving sodium consumption.

Only herbivores crave salt, while carnivores ignore it. This seems to be an important survival mechanism since herbivorous diets lack sodium and carnivorous diets contain ample amounts from flesh and body fluids.

Sodium and obesity

Sodium intake might contribute to obesity, either indirectly or directly via the consumption of processed foods and sweetened, carbonated drinks.

“These pretzels are making me thirsty”

Just a small increase in serum sodium levels can trigger thirst.

A daily excess sodium intake of 3266 mg must be accompanied by a 1 liter increase in water intake to maintain normal sodium concentrations. Ever been really thirsty after Thanksgiving dinner or the Hanukkah buffet? Me too.

Under normal North American circumstances, sweating accounts for about a 58 mg sodium loss each day. If you factor in urine losses, tack on another 180 mg.

If you sweat more than typical North American, you probably lose more sodium. The amount depends on diet, hydration status, and heat acclimatization. Active individuals can lose 800 mg or more of sodium per liter of sweat, making replacement vital.

Without replacement, low blood sodium levels can result. This means cramps, confusion, nausea and disorientation – kind of like a booze bender.

Summary and recommendations

If you consume unprocessed/whole foods, you won’t get sodium levels anywhere near the danger zone.

The people over-consuming sodium are eating processed foods, like microwave meals, canned foods, restaurant food, snack foods, processed meats, dairy, deli meats, frozen meats, cottage cheese and yogurt. If you eat a diet based on processed foods, you’ll probably have high blood pressure and high body fat.

If you eat a diet based on unprocessed and whole foods, sprinkling some salt on your veggies or rice for flavor is fine. Lean and healthy can easily regulate slight increases in salt.

In fact, if you eat a very unprocessed diet and stay physically active, you’ll want to drink electrolyte-rich fluids before, during and after workouts.

For extra credit

Consuming food with lots of salt is linked to stomach cancer, GERD and ulcers.

Early taste experiences with salt can influence lifelong preferences for certain foods.

In July 2009, the Center for Science in the Public Interest sued Denny’s over “dangerously high levels of sodium in its meals.”

Sea salt is produced by evaporation of sea water.

Some people may inherit a “sodium sensitivity.”

Roman soldiers received a salt ration as part of their pay, known as “salarium argentum,” from which the English word for “salary” was derived.

Salt is the muscle behind flour in bread. Salt strengthens gluten in the dough, allowing it to expand. Salt free breads tend to be more compact and dense.

“Take it with a grain of salt” is a well-known phrase that conveys the thought to not take something too seriously.

In those with cystic fibrosis, sodium content of sweat is high.

The ancient Chinese built the first salt empire.

In 1930, Gandhi led a 240 mile march to the sea to make salt, defying a British ban.

Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system kicks in with a consistent low sodium intake (less than 200 mg/day) and increases the retention of sodium and water. 1200 mg of sodium per day suppresses this system.

Dried seaweeds such as kelp and dulse can be used as salt substitutes. They’re also high in beneficial minerals.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Eat, move, and live… better.©

Yep, we know…the health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn’t have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies – unique and personal – for you.

Share