What is cortisol?

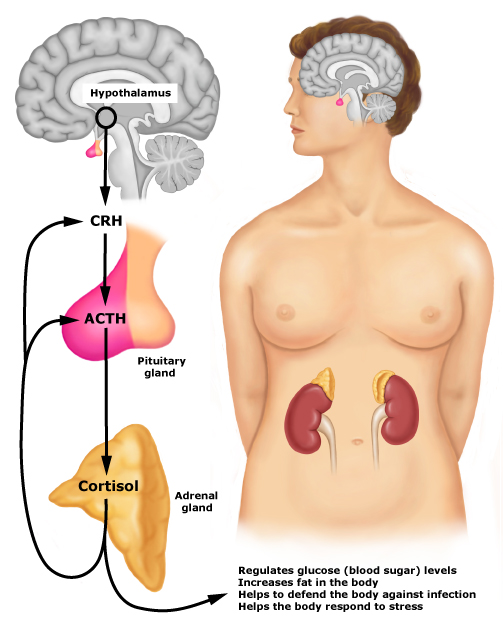

Cortisol is a hormone that belongs to a family of steroid hormones known as glucocorticoids. It’s secreted by the adrenal cortex, which is located in your adrenal glands that sit atop your kidneys. Cortisol is the main glucocorticoid in humans.

Glucocorticoids affect every cell in the body so needless to say, they’re pretty important.

In particular, glucocorticoids released in the body send feedback to the brain and influence the release of CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone) and ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone). ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol. The rise in cortisol secretion follows ACTH release after a 15-minute to 30-minute delay.

Why is cortisol so important?

Cortisol accelerates the breakdown of proteins into amino acids (except in liver cells). These amino acids move out of the tissues into the blood and to liver cells, where they are changed to glucose in a process called gluconeogenesis. A prolonged high blood concentration of cortisol in the blood results in a net loss of tissue proteins and higher levels of blood glucose.

Isn’t this bad?

Well, not exactly. By raising plasma glucose levels, cortisol provides the body with the energy it requires to combat stress from trauma, illness, fright, infection, bleeding, etc.

Obviously, this is bad from a muscle breakdown perspective; however, the body is simply trying to preserve carbohydrate stores and deliver energy when it’s needed most. Acutely, cortisol also mobilizes fatty acids from fat cells and even helps to maintain blood pressure.

As it’s part of the inflammatory response, cortisol is necessary for recovery from injury. However, chronically high levels of cortisol in the blood can decrease white blood cells and antibody formation, which can lower immunity. This is the most important therapeutic property of glucocorticoids, since they can reduce the inflammatory response and this, in itself, suppresses immunity.

Thus, cortisol is:

- Protein-mobilizing

- Gluconeogenic

- Hyperglycemic

Whether these effects are “good” or “bad” depends on whether cortisol’s release is acute (ie brief and infrequent) or chronic (ie ongoing).

What you should know

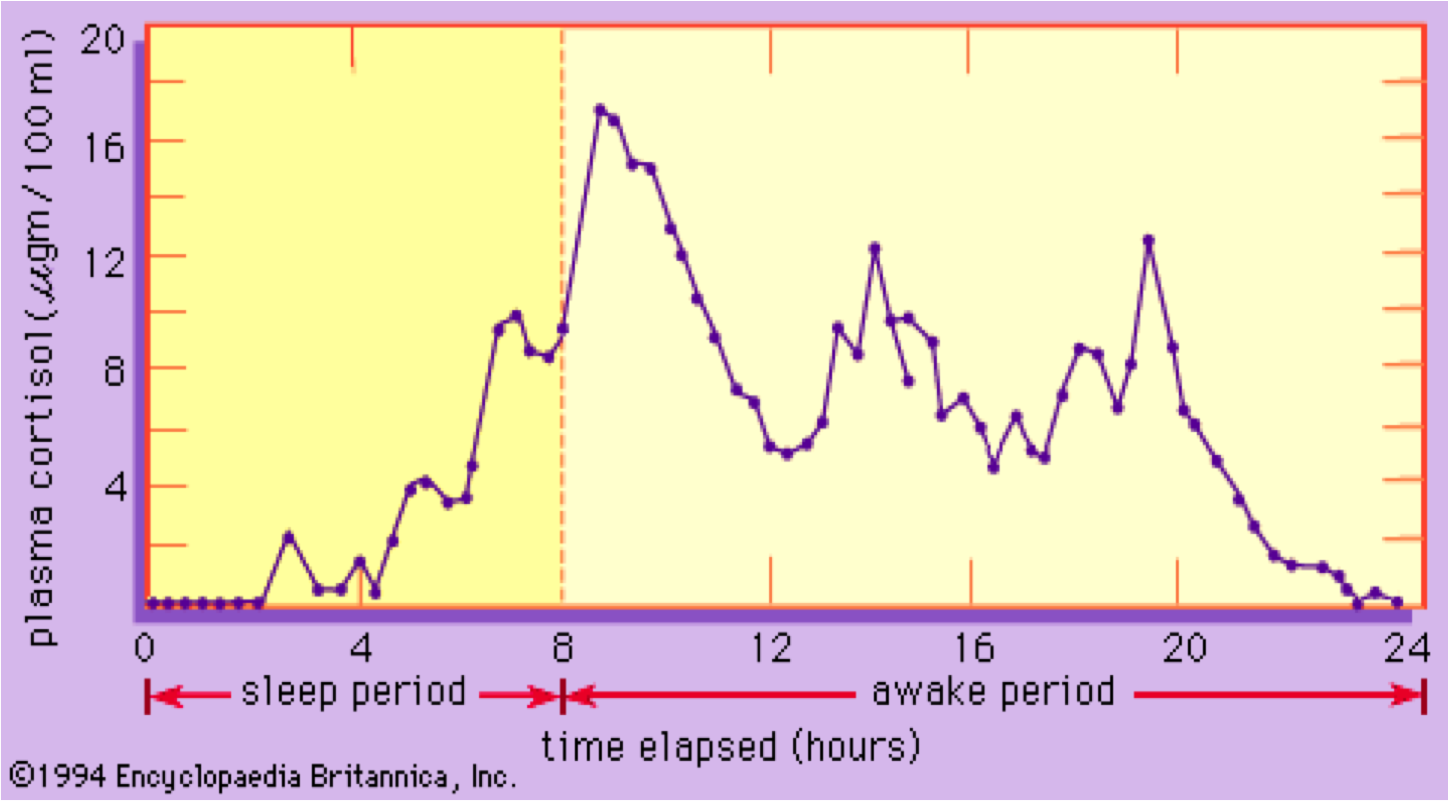

Here are the cortisol reference ranges. Notice that they depend on the mode of measurement (urine vs serum) and time of day.

- Cortisol, free (urine) 20-90 mcg/day

- Cortisol (serum) 4-22 mcg/dL (morning specimen)

- Cortisol (serum) 3-17 mcg/dL (afternoon specimen)

Cortisol has a close relationship to exercise and training status.

For example, cortisol levels can be a sign of overtraining. To be indicative of overtraining, cortisol increases may need to be higher than 800 nmol/L.

Exercise type

The type of exercise regimen performed can dictate hormonal response.

Acute high intensity resistance exercise is associated with increased plasma cortisol concentration. In other words, after something like a sprint or a high-intensity conditioning or bodybuilding-style workout, plasma cortisol concentration increases. The response is similar to that seen of growth hormone. The most dramatic increases occur when rest periods are short and total volume is high.

Cortisol responses to increased training volume are variable. Response depends on specific training protocols and diurnal variations (variations over the course of the day).

Again, it is important to distinguish between acute and chronic cortisol release. When muscle glycogen concentrations are low, cortisol is released and fuel use shifts toward protein or fat so that judicious use is made of the little glucose that remains. However, in the long-term, excessive cortisol will encourage fat synthesis and storage, along with provoking appetite.

On the other hand, aerobic endurance training, particularly running, is linked with protein loss from muscle (partially induced by cortisol). Endurance trained individuals typically have a higher cortisol response, while resistance trained individuals have a higher testosterone response. Secretion of cortisol is elicited at exercise intensities between 80% and 90% of VO2 max, which means that in this case, we’re not necessarily describing recreational exercise — we’re referring to endurance training.

Time of day and time of eating

The degree of cortisol release during high intensity exercise depends in part on the time of day and the timing of meals. When exercise is performed during a time of already high cortisol levels (for example, in the morning), it doesn’t increase above already elevated levels.

Cortisol secretion displays 7 to 15 spontaneous or meal-associated “pulses” throughout the day.

Cortisol circadian rhythms are closely coupled to the sleep-wake cycle. Peak cortisol release occurs between 7 and 9 in the morning, the time of dark-light transition.

The physiological environment

Cortisol causes atrophy in muscle (mainly fast twitch type 2) and bone. The anabolic effects of testosterone and insulin oppose cortisol’s catabolic effects.

The acute increases in cortisol following exercise also stimulate acute inflammatory response mechanisms involved with tissue remodeling. In the short term, this is a necessary response that helps with repairing damage produced by training. Only long-term cortisol elevations seem to be responsible for adverse catabolic effects.

Stress (both psychological and physical) can result in the “alarm reaction.” If stress is ongoing, this can cause enlarged adrenal glands and atrophied lymphatic organs. When adrenals enlarge, they can produce excessive cortisol; when lymphatic organs shrink, they create fewer white blood cells. The immunosuppressive effects of intense exercise have been attributed to high plasma cortisol concentrations that prevail after prolonged intense exercise.

For extra credit

- Excessive secretion of glucocorticoids produces a collection of symptoms called Cushing’s syndrome. One of the symptoms is a redistribution of body fat, known as lipodystrophy.

- Protein and carbohydrate consumption after exercise can offset the cortisol response.

- High blood levels of glucocorticoids can stimulate gastric acid and pepsin production and may exacerbate ulcers.

- Cortisol levels can be up to 50% higher in animals under stress if alone (ie socially isolated).

- Estradiol increases the binding protein for cortisol so that circumstances associated with increased (pregnancy) or decreased (exercise induced amenorrhea and menopause) estradiol alters the amount of circulating free cortisol and its actions.

- Exercising in a depleted state can result in high levels of gluconeogenesis (protein breakdown).

Summary and recommendations

- Take regular, planned breaks from intense training

- Consume enough calories from non-processed foods to prevent depletion

- Get 7-9 hours of sleep per night to decrease stress and cortisol release

- Consume carbohydrates and protein after exercise sessions

- Don’t isolate yourself – spend time with friends and family

- Regularly participate in a stress-relieving activity like mild yoga or meditation

- Avoid excessive amounts of intense aerobic endurance training (unless training for endurance event)

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Eat, move, and live…better.©

The health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn't have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you'll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies – unique and personal – for you.

Share