From TV to computer screens, sexy food images are everywhere. That’s why we have to be careful; food porn stimulates poor choices and overeating. Find out how and why in today’s update. Also, learn what you can do to appreciate food and choose wisely at the same time.

I just watched Silver Linings Playbook. In the film, the main character goes to a diner and orders a bowl of Raisin Bran.

After that scene, all I wanted to do was eat Raisin Bran.

If this subtle cue can make me crave Raisin Bran – a food that isn’t even part of my normal diet – what happens when I watch the Food Network or scroll through recipe blogs?

If you’re trying to lose fat or maintain a healthy weight, this is something to consider.

Indeed, we’re looking at, talking about, and — as a result — thinking about food a lot these days.

Bruce Horovitz of USA Today explains:

“Social-media chatter about food — which is where we do much of it — is up more than 13% over the past year… Food Network, which had 50,000 viewers per night in the mid-’90s, now averages more than 1.1 million.”

And as my Raisin Bran experience shows, pictures and discussions of food can tempt us to eat… and even to overeat.

What’s “food porn”?

Why do we call it “food porn” and not, say, “food pictures”? For that matter, why does the word “porn” appear on PN at all?

Sure, originally the word “pornography” referred specifically to images of sex. But now, it’s used more broadly to refer to the commodification, simplification, and simulation of an experience, person, or thing.

Porn presents a world where everything is better than reality. Porn packages up a part of life into a shiny, visually appealing, easily consumed fantasy package.

So you can have “lifestyle porn” (think Martha Stewart), “house porn” (think Architectural Digest), or heck, even “knitting porn“.

And porn creates desire. It taps in to our primal “me want that” brain.

Thus, food porn isn’t just pictures of food. After all, images of food from previous eras were somewhat unsophisticated.

You probably don’t want to dig in to this dinner party special from the 1960s.

But nowadays, food is an industry — an industry that includes skilled photographers and designers, food stylists, product developers, celebrity chefs, social media, and reality TV as well as thousands of websites and amateur food bloggers.

Food looks a heckuva lot better than it used to. Images of appealing food are everywhere now. And these images can and do affect our food choices.

Why we eat

Eating patterns are influenced by many factors, including:

- Gut/brain cues (e.g., low blood sugar, growling stomach)

- Learned behaviors (e.g., it’s lunchtime at noon)

- Thoughts (e.g., I’m on a low carb diet; I haven’t eaten for 3 hours)

- Habits (e.g., cookies every night before bed)

- Social context (e.g., it’s a party with food, so I’ll eat)

- Food availability (e.g., I’m out of vegetables, so I won’t eat them)

- External / environmental cues (e.g., images of food, cooking shows, food blogs).

And it turns out that looking at food, or even pictures of highly palatable food, can chronically activate our desire to eat – even in the absence of true physiological hunger.

That’s because we don’t just eat to satisfy our nutritional requirements. We also eat for pleasure.

Pleasure & palatability

Highly palatable foods (in other words, foods that taste extra-good) are highly pleasurable foods. And when we get highly palatable foods, we — and other mammals — will eat more of those foods than our bodies need.

Highly palatable foods also look good to us. Whether it’s a juicy burger or a shiny jellybean, highly palatable foods are specifically constructed — yes, constructed — to appeal to all our inherent preferences.

We don’t usually overeat low-palatability foods such as beans, meats, vegetables, and whole grains. And few people would really call lentils or a hunk of chicken sexy.

But when low-palatability foods are processed or otherwise altered to become vehicles for sugar, oil, and salt, suddenly they become a whole lot more palatable. It’s the difference between a plain baked potato and a bowl of potato chips.

Attractive food images can make us want highly palatable food more. And they can also increase our desire for less-palatable food.

What you see is what you want

Head to the grocery store. Notice all that candy by the checkout? It’s strategically placed.

We often regret impulse purchases of candy and swear we’ll avoid them in future. But our willpower is low after a trip through the grocery store, especially if we shop after work before mealtime, as many of us do. Food companies and grocers know this.

You see the product. It’s shiny and looks good. BAM! You’re hooked. You make the purchase.

If you never saw the product, you likely wouldn’t have looked for it and bought it.

Moreover, certain things can make us more or less receptive to food cues.

We’re more likely to want food when we’re in certain situations or moods — for example, when we’re restricting our food intake, or when our blood sugar is low.

Of course, dieters are more vulnerable

When we’re dieting and/or restricting food we tend to be more sensitive to food images. And if our blood sugar levels are low (like, if we’re shopping when we’re hungry), images of food can send us right over the edge – and into the fridge.

Remember the Ancel Keys “starvation experiments”?

Participants in this study agreed to a grueling low-calorie diet designed to mimic the semi-starvation diet of wartime civilians. (Researchers were hoping to learn how to help victims of deprivation in the post-war period.)

During the “underfeeding” phase, participants in the Keys study became obsessed with cookbooks and pictures of food. One man reported owning nearly 100 cookbooks by year’s end!

In line with this, many dieting physique athletes (bodybuilders and physique competitors) report the same thing.

Also, food advertising works

Do you think food advertisers know about our vulnerability? Definitely.

There’s a reason the Institute of Medicine (IOM) is quoted as saying, “Advertising works.” The more a company spends on advertising a certain food, the more the company sells of that food.

Not only does advertising make us want to eat, it makes us want to eat specific foods – namely, the highly palatable foods that companies promote.

Thus when exposed to appealing food images, we don’t just want to eat more in general. We want to eat more of particular foods — foods that typically make us fatter and unhealthier when we eat too much of them.

(See Research Review: Does food branding make kids obese? for more.)

And we’re surrounded

Obvious junk food may tempt us. But these days, it’s not the only threat. With all the “healthy living” food blogs, magazines, and newsletters piling into our in-boxes, we may even feel compelled to overeat supposedly nutritious foods.

Those hemp açai vegan super snacks, kale chocolate smoothies, Paleo muffins, and gluten-free cookies may (or may not) be healthy. But you can overeat them just as you can overeat a box of Twinkies.

So – a quick recap:

- The sight of food is a key signal to begin a meal, especially when we are hungry or restricting food.

- Meanwhile, more and more of us restrict food or say we are dieting, which makes us more receptive to food cues.

- And we’re constantly exposed to food blogs, commercials, and shows.

Yikes. It sounds like a recipe for weight gain.

Why we respond differently to visual food cues

But wait. Images of food don’t affect everybody the same way. There is some variability in how we respond.

Why?

Food / eating restriction makes us more sensitive

First, as we’ve already noted, restrained eating or dieting seems to make us more sensitive to visual food cues.

Those who put particular foods off limits tend to be more sensitive to external cues for those foods. This might explain the saying, “There’s a binge for every diet”. And it seems to occur independent of body size.

Individuals who’ve recently lost body fat and are getting used to a new body are especially vulnerable to visual cues.

Perhaps this is because in order to lose weight they have had to be preoccupied with food, at least to some extent – managing portion sizes, learning to cook differently, and so on.

Imagination makes us more sensitive

Food-reward-activity lighting up in the brain seems to hinge on imagination.

If we see an image of food but don’t actually imagine eating it, or the taste of it, the brain doesn’t light up in the same way.

So, seeing a picture of a palatable food when your brain is focused elsewhere won’t inspire you as much.

For example, if you just found out your dog has cancer, or you have a major work presentation in 10 minutes, even the tastiest-looking foods won’t seem as appealing.

So, when our brains are otherwise engaged, we’re less likely to eat after viewing food images.

Tolerance make us eat more

The classic “cue-trigger” response goes like this:

1. A cue appears (e.g., a new cookie recipe on a food blog or the liquor store’s sign as we drive past).

2. The cue then triggers an action: Seeking out a cookie or a drink.

Problem is, regular exposure to this trigger (whether it’s a highly palatable food or alcohol) can cause us to build tolerance. As tolerance builds, we need more of the desired substance to get the hit of satisfaction we’re seeking.

Three years ago, one cookie would have done the trick. Now it takes five cookies chased with a mocha latte.

So those who have built tolerance will not only eat, they will eat more in response to cues like food imagery.

Overweight / obese folks get a greater response

Folks who are obese and/or have binge eating disorder seem to have a hyperactive reward system when it comes to certain foods.

In other words, “problem eaters” tend to have a higher hedonic drive to eat. And their brains light up more when they’re shown pictures of palatable food.

Hedonic hunger = the pleasure associated with the consumption of highly palatable foods and the imaginative craving of food whether truly hungry or not.

“Problem eaters” aren’t the only people who struggle with hyperactive reward systems in the brain. This occurs with various forms of addiction too.

For example, “problem gamblers” shown pictures of gambling have greater brain activation in areas related to emotion-motivation and attention-control than “problem gamblers” shown neutral pictures.

Many people find they’re less hedonically hungry after gastric bypass surgery. Their gut and brain might be interacting differently. There also might be a “learned” component, since eating a lot of of rich foods after gastric bypass causes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

This negative association might lead to decreased consumption, just like an experience of food poisoning might make you avoid the food that caused it.

Dieters become disinhibited and can overeat

Non-dieters, who eat in an unrestrained and normal way, tend to regulate their food intake pretty easily according to internal cues of hunger and fullness, as long as they select minimally processed foods.

For instance, after a big meal, they’ll unconsciously choose a smaller or less energy-dense meal. A day of indulgence will lead to a day of relatively lighter eating.

Dieters, however, react in the opposite way. When dieters overeat, they don’t respond by slowing down or stopping. Instead, they tend to eat more.

Eating lots of food can dis-inhibit a dieter’s usually inhibited eating. It’s almost like flipping a switch: “I’ve blown it anyway, so I might as well keep eating before I go back on my diet.”

Contrary to what we might expect, many dieters find food even more appealing when they’re full than when they’re physically hungry.

Greater activity in the reward centers of the brain and less activity in the areas related to cognitive control might contribute to disinhibited eating.

It is an almost irresistible urge to eat beyond comfortable satiety. And food images can trigger disinhibition.

Insulin helps reduce hunger, unless we’re resistant

Insulin doesn’t appear to be influenced directly by food images. But after eating, insulin does act directly in the brain, affecting satiety or that feeling of “fullness”.

Lean folks seem to be more sensitive this message. This might indicate potential insulin resistance in the brains of individuals with more body fat.

Translation: Insulin secretion after a meal helps lean people feel more full and makes them less sensitive to visual food cues.

But in people with more body fat (and less insulin sensitivity), this response is dulled. They feel less full after eating and are more vulnerable to images of food.

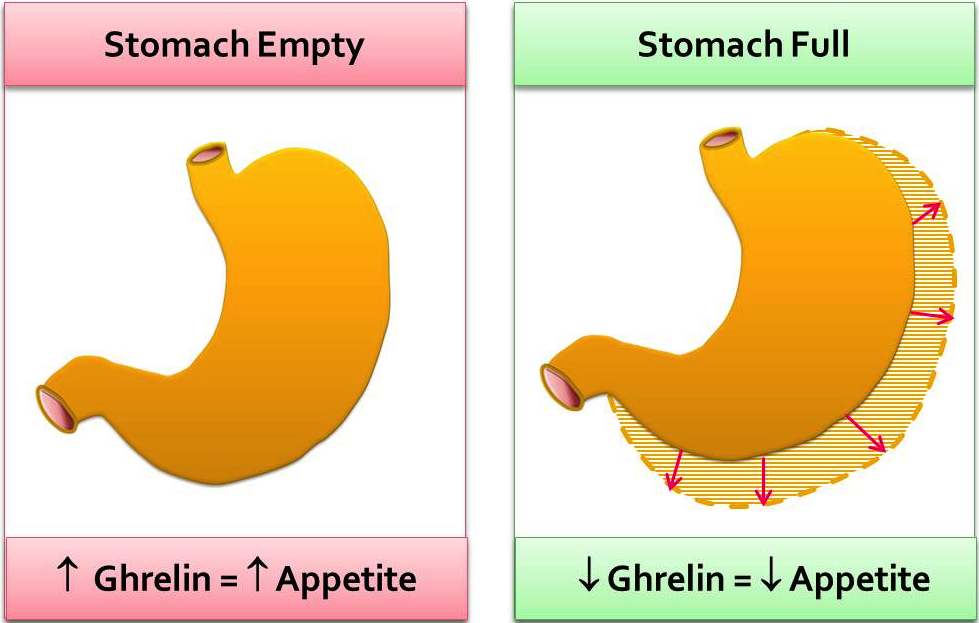

Ghrelin sensitizes us to food cuing

Have you ever caught yourself daydreaming about a favorite food or meal? Ghrelin probably played a role in this.

Ghrelin is a hormone secreted by the gut that encourages food intake. It’s thought that ghrelin acts partially through the vagus nerve. (It also seems that ghrelin can cross the blood brain barrier directly.)

Ghrelin is high before a meal and low after a meal. More ghrelin means we’ll seek out food. Ghrelin also seems to be related to other drug-seeking behaviors.

The more ghrelin floating around the body, the more sensitive we are to external food cuing (e.g., images of food). And the sight of food (or images of food) can lead to higher levels of ghrelin floating around the body.

In evolutionary terms, it’s a highly useful cycle, promoting regular eating for species survival. But it’s not so useful if you’re marinating in food pictures while trying to stay lean.

Women have a stronger response to food images

Women may have a stronger response to external food-related stimuli (including images of food) than men.

Some researchers suggest this may be due to the menstrual cycle and reproductive hormones. Maybe it helps to explain why women are at a higher risk for disordered eating.

But stronger brain activation might not always be a negative force. Stronger brain activation could also lead to a stronger satiety response after meals, which could in turn result in tighter control of appetite.

Disordered eating changes desire for food

Studies of people diagnosed with anorexia nervosa suggest that even when shown images of food, their desire for food stays unchanged.

Reclaiming this desire might not be possible, as brain circuitry appears to be permanently altered, even in weight-restored patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa.

This is sobering information. Not only do hunger cues serve a vital biological function, but the pleasure we derive from (healthy, moderate) eating is one of the greatest gifts of life.

Perhaps this can help us to put food imagery into perspective. Images of food aren’t evil.

In fact, if we understand the power of visual food cues, we can even use them to our advantage.

Some potential solutions

Here are a few ideas to help you handle the onslaught of food imagery and take control over your urges.

Embrace the drive to eat.

Eating is a normal function. We need to eat to survive.

And, knowing what you now know about the sight of food and its power over us, if you want to eat more of a certain food, put it on display.

Put it on the eye level shelf of the fridge and pantry. Watch recipe videos and look at cookbooks that use the food.

Meanwhile, if you want to eat less of a particular food, put it out of sight or don’t buy it at all.

Learn your hunger.

Learn the difference between “need to eat” (physiological hunger) and “want to eat” (psychological hunger or desire stimulated by food cues).

Know yourself.

You’ll probably be more receptive to attractive food images if you:

- have more body fat (perhaps because of insulin)

- are hungrier

- are restricting food.

Even if you aren’t normally affected by food images, you might also be more cue-receptive or easily triggered in certain situations or moods. Know your vulnerabilities.

Recognize food porn when you see it.

As the classic line about porn goes, “I can’t define it, but I know it when I see it.” The same is true of food porn.

When you feel compelled by appealing food images, stop and notice that. Think about what makes those images so appealing to you.

Is it the look (oh-so-delicious)? The time when you see those food cues (i.e. late-night commercials)? The place where you see those images (e.g. in the supermarket)?

Recognize that manufacturers and marketers desperately want you to consume this stuff, and they know that images are powerful.

Slow down.

Triggers depend on our automatic response. Pause. Take a moment. Decide slowly. Eat slowly.

This will keep you in control.

Limit your exposure.

Make life easier for yourself. If you know you are sensitive, avoid excessive cuing of foods you don’t want to eat.

If you find yourself cruising food blogs looking for a “hit”, or rooting in the kitchen after food commercials, think about how to adjust your environmental food stimuli to filter out those cues.

And, as Michael Pollan advises, “Treat treats as treats.”

Distract yourself.

If you get caught up in food cuing, distract yourself. Place your focus elsewhere.

Notice how often your thoughts go to food when you’re bored. Do you need something else to engage you?

Get meals delivered.

Getting meals delivered prevents time spent reviewing recipes, preparing meals, buying ingredients, etc. In other words, you spend less time focused on food.

Of course, make sure you’re ordering healthy meals. Most cities have sources of healthy meal delivery.

Plan a menu for the week.

A plan prevents impulsive decisions and overthinking about food. And plan when you’re feeling safe, solid, smart, and secure.

Don’t try planning at, say, 7 pm after a tough day at work.

Self-experiment.

Eliminate your sources of food porn/food advertising.

See if you notice a difference. Keep a journal.

Consider your career.

Whether you’re a nutritionist or chef, working with or around food will leave you thinking about food more.

Spread the word.

Educate kids on how the brain responds to food imagery to prepare them for healthier lives.

Disconnect.

Disconnect food images from the cascade of imagining the taste, the eating experience, and so on.

If you absolutely cannot separate the two, it might be best to avoid food imagery until you actually want to eat.

Conclusion

“Food porn” is impossible to miss in our food-obsessed culture. And there’s no question that images of food can tempt us to eat, even overeat.

But with a little bit of knowledge and some forethought, you can exercise control over how food images will affect you. Whether it’s your eating behaviors, weight, or body composition.

Remember, food images aren’t evil. Yes, you do have to be careful. But, then again, you can also use food images proactively; to help to change your eating habits for the better.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Learn more

Want to get in the best shape of your life, and stay that way for good? Check out the following 5-day body transformation courses.

The best part? They're totally free.

To check out the free courses, just click one of the links below.

Share