When is a calorie not a calorie? When it comes from from whole (versus processed) food.

Most of us know Dr Mark Haub, the nutrition professor who lost 27 pounds on the junk food diet.

Great. As if the North American diet wasn’t bad enough, we’ve now got a nutrition professor promoting eating candy bars and Twinkies to lose weight.

He has two key points for his argument and experiment:

- A calorie is a calorie is a calorie. For example, 100 calories from a candy bar and 100 calories from kale are the same.

- If you eat fewer calories than you use, you will lose weight.

I can’t argue point #2 since it’s a basic law of thermodynamics, but point #1 is flawed in a few ways.

When a calorie isn’t a calorie: Thermal effect of food

Calories are a measure of energy. Weight change depends on the balance between two things: energy in versus energy out.

Energy out includes obvious things like:

- physical activity (activity metabolism)

- energy to keep you alive at rest (basal metabolic rate)

- energy added to the body like amino acids to muscle, and fat to fat tissues

And less obvious things like:

- energy lost in waste (feces and urine)

- energy used to digest the food you eat

Energy in seems simple: How many calories were in the spinach salad, bagel or ice cream sandwich you ate?

Turns out, energy in is just as complex as energy out, because of the energy cost of digesting food.

Digesting food costs energy

Ever wonder how celery has negative calories? It takes more energy to break down and absorb the celery than the celery contains.

Eating costs calories: calories to chew, swallow, churn the stomach, make the acid in the stomach, make the enzymes, to make the rhythmic muscular contractions known as peristalsis that drive the food through, and so forth.

Scientists have three names for this phenomenon:

- dietary-induced thermogenesis (DIT);

- thermal effect of food (TEF); or

- specific dynamic action (SDA).

On average, a person uses about 10% of their daily energy expenditure digesting and absorbing food, but this percentage changes depending on the type of food you eat.

Protein takes the most energy to digest (20-30% of total calories in protein eaten go to digesting it). Next is carbohydrates (5-10%) and then fats (0-3%).

Thus, if you eat 100 calories from protein, your body uses 20-30 of those calories to digest and absorb the protein. You’d be left with a net 70-80 calories. Pure carbohydrate would leave you with a net 90-95 calories, and fat would give you a net 97-100 calories.

Hmm. Maybe “a calorie is a calorie” doesn’t hold up after all.

Research question

In the study I’m reviewing this week it seems that not only does macronutrient content change TEF, but processing changes TEF.

Barr SB and Wright JC.Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed-food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure. Food Nutr Res. 2010 Jul 2;54. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v54i0.5144.

Methods

The study compared what happened when 17 volunteers ate a whole food meal versus a processed food meal. Volunteers were all of normal weight, and about 25 years old.

The meals

The researchers use the term meals rather loosely, since these meals were cheese sandwiches. In this study, the metabolic impact of whole food sandwiches made of multi-grain bread and real cheddar cheese were compared to processed food sandwiches that were made with white bread and processed cheese product.

Though the researches call the sandwiches whole food and processed food, both are processed, but just to a different degree.

Table 1: Energy composition of the two test meals, 800 kcal portions

| Whole food meal | Processed food meal | |

|---|---|---|

| Serving | 2 sandwiches | 2 sandwiches |

| kcal | 800 (3,360 kJ) | 800 (3,360 kJ) |

| Total fat | 35 g (39%) | 29 g (33%) |

| Total carbohydrate | 80 g (40%) | 99 g (50%) |

| Dietary fiber | 12 g | <6 g |

| Sugars | 16 g | 16.5 g |

| Protein | 40 g (20%) | 30 g (15%) |

| Total dry weight | 154 g | 158 g |

Table 2: Energy composition of the two test meals, 600 kcal portions

| Whole food meal | Processed food meal | |

|---|---|---|

| Serving | 1½ sandwiches | 1½ sandwiches |

| kcal | 600 (2,520 kJ) | 600 (2,520 kJ) |

| Total fat | 26 g (39%) | 22 g (33%) |

| Total carbohydrate | 60 g (40%) | 74 g (49%) |

| Dietary fiber | 9 g | <4.5 g |

| Sugars | 12 g | 12.4 g |

| Protein | 30 g (20%) | 23 g (15%) |

| Total dry weight | 116 g | 119 g |

Table 3 lists the ingredients for cheese and bread in the whole and processed sandwiches.

I don’t really think I’d call either of these “whole” foods. While the whole food sandwich has fewer unnecessary ingredients like the annatto (vegetable color) in the cheese, and guar gum in the bread, it also contains brown sugar, vegetable oils, and soy lecithin.

The “whole” food example could certainly be better, but on the other hand, it’s kind of hard to fool people about what they’re eating to keep them unbiased when the choice is an apple (whole) versus apple juice (processed). So perhaps this was the best-possible option.

Table 3: Cheese and bread ingredients

BreadStone-ground whole wheat flour, water, brown sugar, wheat gluten, yeast, contains 2% or less of each of the following: vegetable oil (soybean and or/cottonseed oils), whole wheat, sunflower seeds, rye, cultured wheat flour, salt, raisin juice concentrate, oats, barley, corn, millet, triticale, distilled vinegar, guar gum, enzymes, enzyme-modified soy lecithin, wheat bran, soy flour.Unbleached enriched flour [wheat flour, malted barley flour, reduced iron, niacin, thiamin mononitrate (vitamin B1), riboflavin (vitamin B2), folic acid], water, high fructose corn syrup, yeast, soybean oil, salt, wheat gluten, calcium propionate (preservative), monoglycerides, datem, ascorbic acid (dough conditioner), soy lecithin.

| Whole | Processed | |

|---|---|---|

| Cheese | Pasteurized milk, cheese culture, salt, enzymes, annatto (vegetable color), Natamycin (A natural mold inhibitor). | Milk, whey, milkfat, milk protein concentrate, salt, calcium phosphate, sodium citrate, whey protein concentrate, sodium phosphate, sorbic acid as a preservative, apocarotenal (color), annatto (color), enzymes, vitamin D3, cheese culture. |

Eating and energy

After not eating for 12 hours (overnight), researchers measured the volunteers’ basal metabolic rate using oxygen consumption.

Then the volunteers were randomly given either a processed food sandwich or whole food sandwich (portion size was up to the volunteer). Then volunteers’ metabolic rate was measured every hour for six hours after the sandwich (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 hours post-sandwich).

2-6 days later, volunteers came back into the lab and did exactly the same thing, but with the other sandwich.

Results

People tend to think healthier food tastes worse than less health food, but in this study the volunteers rated the whole food sandwiches as more palatable (6.5/10) compared to the processed food sandwiches (4.9/10), with no differences in how energetic they felt after eating the two sandwiches. And they felt no differences in fullness aka satiety (see Figure 1).

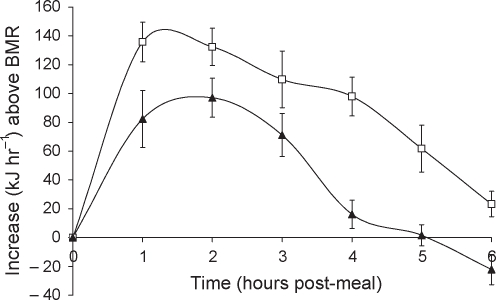

However, eating whole food took 46.8% more energy to digest on average than processed food!

The total energy (TEF) needed to digest and absorb a whole food sandwich was 576 kJ. The TEF for the processed food sandwich was 310 kJ.

Figure 2 gives you a hour-by-hour average increase in metabolic rate from basal metabolic rate over 6 hours after eating the sandwiches.

Figure 1: How satisfying are processed foods (open triangles) vs. whole foods (white squares)? |

Figure 2: Changes in BMR over time in processed foods (open triangles) vs. whole foods (white squares) |

What explains the differences?

Protein and fiber play a part.

In Table 1 above, we can see that the whole food sandwich had more had more protein (40 g) and fiber(12 g) than the processed food sandwich (30g protein and <6 g fiber). This explains the differences in TEF between sandwiches, but not entirely.

Conclusions

As Dr. Mark Haub showed, you can lose weight eating processed junk food. But he could have eaten a lot more whole food (that had important nutrients) and lost the same amount of weight.

If you didn’t have enough reasons to avoid processed food when losing weight, add reduced thermal effect of food to the list.

Processed food takes less energy to digest and absorb compared to whole foods, so 100 calories of processed food ends up being more net calories than 100 calories of whole food.

If you’re trying to lose weight, eat whole foods. If you’re trying to gain weight (such as you Scrawny to Brawny guys), you may find that you need to include a little more processed food for a while.

Bottom line

What is truly “whole” food?

When judging what’s “whole” and “processed” foods, ask yourself:

- What’s on the ingredient list?

- Do I recognize all these things?

- How many steps did this food take to get to me?

- Does this food come in a bag, box, or can?

For a real eye-opener, next time you’re at the grocery store, take a look at the ingredients of a few different brands of yogurt and compare the ingredients. Good quality plain yogurt will have two ingredients: milk and bacteria. Other so-called yogurts will have things like sodium citrate, corn starch, gelatin, pectin, calcium phosphate, potassium phosphate and sodium phosphate.

By the way, you might also be surprised to see what is in cream. Yep, plain old cream is often actually milk with cheap emulsifiers and sweeteners such as dextrose.

Read labels and buyer beware!

And if your food normally comes in a tube… well, you might consider learning a few new cooking skills.

Eat, move, and live…better.©

The health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn't have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you'll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies – unique and personal – for you.

Share