In this week’s case study, Dr. Detective meets a teenager who’s always tired. He’s anemic — but he can’t absorb iron. Read on to discover why you are what you digest, not what you eat.

Eat less and exercise more. It’s generally a great prescription for improving health and improving body composition. However, it doesn’t always work.

Even with an awesome exercise plan and a rock-solid diet, some people suffer from mysterious symptoms and complaints that seem puzzling, given how much effort they put into their fitness and health.

When we meet clients who have problems that exercise and nutrition — not to mention their own doctors — can’t seem to solve, we know there are only a few experts on the planet to turn to. One of them is Spencer Nadolsky.

Dr. Nadolsky is a doctor of osteopathic medicine who’s also studied exercise physiology and nutrition. An academic All-American wrestler in university, he’s still an avid exerciser and brilliant physician who practices what he preaches to patients -– treating preventable diseases first with lifestyle modifications (instead of prescription drugs).

When clients have nowhere else to turn, Dr. Nadolsky turns from a cheerful, sporty doctor into a meticulous, take-no-prisoners forensic physiologist. He pulls out his microscope, analyzes blood, saliva, urine, lifestyle – whatever he has to, in order to solve the medical mystery.

When Dr. Nadolsky volunteered to work on a regular case study feature with us, we jumped at the chance. By following along with these fascinating cases, you’ll see exactly how a talented practitioner thinks. You’ll also learn how to improve your own health.

In today’s case, we’ll meet a young football player who came to Dr. Nadolsky with a single complaint: low energy. Upon further investigation, Dr. Nadolsky discovered inadequate iron levels. Straightforward, right? Just prescribe some ferritin and send him on his way.

But the client’s low energy — and low iron — persisted. Turns out he wasn’t digesting his foods well. Read on to find out why, and how Dr. Detective got him back in the game.

The client

Jake, a 17 year old male football player, came to the sports medicine office for “decreased strength and endurance”.

Square-jawed and chiseled, Jake looked like a typical high school linebacker. In a sports medicine clinic, we generally see these kids for injuries rather than illness. Right away, I went on the alert.

Jake didn’t seem acutely sick. But he didn’t look like he had seen much sun lately, either. Pale, tired, and a teenager — my first guess was a simple case of mononucleosis.

The client’s signs and symptoms

Jake’s story didn’t sound too unusual. He just felt less energetic. Also, he found it tough to get through his team’s conditioning regimen. And he’d been feeling this way for about a year.

So much for my first theory! Mono symptoms wouldn’t have lasted so long.

Next, I asked Jake about sleep. Many teens sleep erratically and this can seriously affect their energy levels. But Jake claimed to maintain a strict schedule. He went to bed at 10 pm and woke at 6:30 am. That’s better than most adults!

When asked about his diet, Jake said it hadn’t changed much over the past few years. But a little probing revealed that he relied a lot on processed foods — cereal for breakfast, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for lunch, granola bars for snacks, and pasta for dinner, along with some meat and maybe a few veggies.

By now I suspected that his diet might be causing his problems, but I still needed to dig deeper. After all, he’d been eating this way for a long time — and the symptoms were relatively new.

Also, his symptoms were fairly non-specific (meaning they don’t point to any one disease). Jake described the following:

| Signs / Symptoms | My thoughts – potential issues |

|---|---|

| Tired all day | Thyroid, anemia, sleep issues, overtraining, depression |

| Loss of endurance | Thyroid, anemia, poor diet |

The classic symptoms of thyroid problems include dry hair and skin and constipation. Jake didn’t complain about these. That didn’t mean he couldn’t have thyroid problems. It just meant I’d look for other explanations first.

For example? Depression. That can manifest in unusual ways — excessive tiredness being one — particularly in teenagers. Luckily, a depression screening questionnaire showed that Jake was actually a fairly happy-go-lucky guy. Just frustrated because he felt so tired!

After thoroughly interrogating Jake about his health, I examined him top to bottom. He was roughly 6 feet tall, 175 pounds, and about 13% body fat. My osteopathic exam showed no structural abnormalities (other than the usual rounded shoulders). His thyroid gland was not enlarged and his tonsils were normal sized. I heard no heart murmurs; his abdomen was lean and non-tender.

But he did look unusually pale. Too much time playing video games, or anemia? My guess would be the former. Anemia’s quite common in teenage girls (due to their menstrual cycles) but it’s very unusual in a teenaged boy.

The tests and assessments

A standard workup for fatigue in a teenager like Jake would simply include a complete blood count and a test for thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). But often, the labwork for patients complaining of fatigue will look normal.

Test results – round 1

Blood chemistry panel

These are Jake’s preliminary lab findings:

| Marker | Result | Lab Reference Range | Thoughts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 11.2 g/dL | 12.5-17.0 | Low – Slightly anemic |

| Hematocrit | 33.7% | 36.0-50.0% | Low – Slightly anemic |

| WBC | 6.0 x10E3/uL | 4.0-10.5 | Normal |

| MCV | 74 fL | 80-98 | Low- Consistent with microcytic anemia |

| TSH | 1.10 uIU/mL | 0.450-4.5 | No suspicion of thyroid issues right now |

No wonder Jake felt tired: He was slightly anemic. Further lab testing showed an elevated TIBC (total iron binding capacity) along with a low ferritin, pointing to an iron deficiency anemia.

Why would a teenage boy have iron deficiency anemia? I knew Jake was chowing down on highly processed cereals and grains without much meat in his diet, but even processed foods are generally fortified with iron. Nonetheless, my prescription for him was simple:

- Include more meat in the diet.

- Supplement with ferrous sulfate.

- Come back in one month for follow up and more testing.

A month passed and Jake returned. It didn’t take long to establish that my prescription hadn’t done much to help him. At first I was worried I had missed a thalassemia (a hemoglobinopathy that might fool you into a iron deficiency diagnosis), but since ferritin and TIBC are generally normal in thalassemias, that didn’t make sense. So what was I missing?

Time for more detective work. And that meant questions. I can’t emphasise it enough: A patient’s history is more important than the physical or even the lab tests. The history is what clues you into making the correct diagnosis.

This time, in reviewing Jake’s symptoms, I decided to focus more on his gastrointestinal system. Iron deficiency in older folks can be a sign of possible colon cancer, but Jake reported no dark or bloody stools. He did admit that his stools had been looser lately, but that, he figured, was just because of nervousness about school or sports. As a matter of fact, Jake couldn’t remember the last time his stools were completely formed.

Hmmmm. I asked him if he had any family history of any inflammatory bowel diseases or autoimmune diseases. Nope.

Now some, at this point, some might diagnose him with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and send him on his way. But the combination of his GI symptoms and iron-deficiency anemia made it clear that he wasn’t efficiently absorbing the iron supplements or even the iron in the foods he was eating.

Was it time to give up and just refer him to a hematologist (a doctor who specializes in blood) or a gastroenterologist (a doctor who specializes in the GI tract)? Not for Dr. Detective! I wasn’t going to give up that easily!

Given Jake’s highly processed diet comprised of mostly cereals and grains, I started getting suspicious about celiac disease. Patients with celiac disease who eat gluten-containing foods will damage their intestines to the point where they don’t absorb vital nutrients.

Time for a few more tests and yet another follow-up appointment.

Test results – round 2

Blood chemistry panel

Here are Jake’s second round lab findings:

| Marker | Result | Lab Reference Range | Thoughts |

|---|---|---|---|

| anti-IgA tissue transglutaminase antibody level | 5.8 units | <1.0 units | Likely celiac disease |

| anti-IgA endomysial antibody titer | 1:360 (positive) | 1:10 | Likely celiac disease |

No wonder Jake was iron deficient. He wasn’t absorbing much of the iron he was eating! Apparently you aren’t what you eat, but what you digest.

Jake’s follow up

Jake wasn’t too happy to hear he had celiac disease. In fact, he was distraught that he wouldn’t be able to enjoy some of his favorite cereals and breads.

At this point, I could have wagged my finger at him and told him to lay off the junk. Instead, I took another route. Jake hopes to play football in college someday. That means he needs to gain a bit more muscle on his frame and improve his performance.

Instead of berating him, I used Awesomeness-Based Coaching. (For more on ABC, see our free 5-day course for fitness pros.) I explained to him that this was holding him back from being awesome… and I outlined a diet that could help him reach his goals while calming his irritated digestive system.

The prescription

Fix #1 – More protein and zero gluten in each meal

This was crucial—but how could Jake manage it easily? Here’s some good news: With a bit of planning and prep work, he could live normally. In fact, the strategies for doing this are helpful for anyone trying to make dietary change.

I suggested four key strategies, one for each meal.

Strategy 1: Find a few “go-to” meals.

A “go-to” meal is a meal that you like, a meal that meets your requirements, and a meal that you can make easily, over and over. You don’t have to think about a “go-to” meal or fuss with it. It’s a habit that makes dietary change seamless. Having a few “go-to” meals in your mental roster means that you’re always prepared to eat healthily, no matter what.

I suggested that Jake come up with two easily-made types of breakfasts that would be his “go-to” morning meals. On lifting days, he could have a gluten-free bowl of cereal plus a protein shake. On non-lifting days, he could eat 4 eggs with two pieces of turkey bacon/sausage and a V8 juice.

Strategy 2: Get creative in the cafeteria.

Almost every restaurant or cafeteria has healthy options available. You might just need to get creative. (And I’m the master of finding good stuff in hospital cafeterias, so you’ll have to trust me on this.)

Jake was used to eating ravioli or some other pasta dish each day at school for lunch. Luckily the hot bar also served grilled chicken sandwiches; he just had to stay away from the bun. Jake agreed to that, but a chicken breast on its own wasn’t going to fill him up. Luckily, as an alternative to pasta, the hot lunch line also offered either beans, rice, or both — and Jake liked these. I also encouraged him to grab a piece of fruit or a veggie.

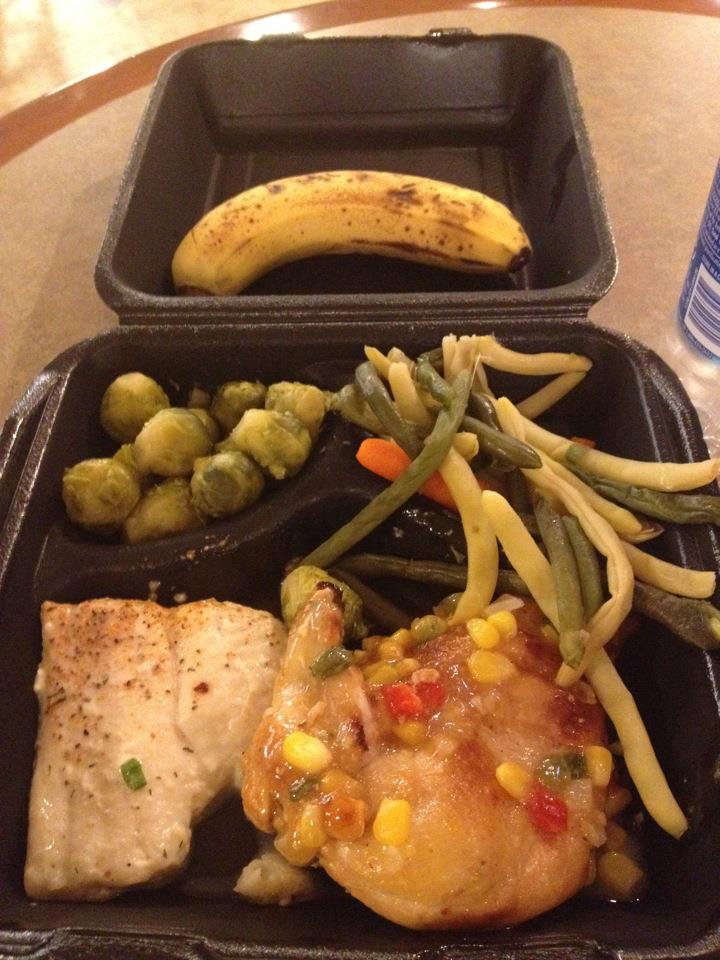

Here are a few examples of my own, gluten-free, hospital cafeteria-foraged meals. (Bear in mind, I’m a large, relatively young, active male. My diet looks a lot like what I’d prescribe to a teenage male football player. Scale down portion sizes accordingly and reduce the carb portion if you are a small female, older, and/or less active!)

|

|

| An “anytime” lunch: Veggies, chicken, and a banana for dessert. Less active people can easily eliminate the banana. | A “postworkout” breakfast: Eggs, bacon, cottage cheese, and sausage with extra potatoes and fruit |

Strategy 3: Find healthy snacks… and treat them like “real food meals”

“Snacks” are no different from “meals” in my universe. They can be smaller, perhaps more convenient or portable, but in terms of nutritional principles, they’re not different. “Snack time” does not mean “junk food time” or “ignore nutritional guidelines time”. The trick is to find “snacks” that meet the requirements. (See “go-to” meals… the same idea applies here.)

I asked Jake to substitute a protein shake and a piece of fruit for his usual cereal bars. He liked apples and even asked if he could put some peanut or almond butter on top. Naturally, I said yes.

Strategy 4: Find simple substitutes; get help

Sometimes making dietary changes is as simple as reshuffling the makeup of an existing meal. And often, there are resources and people around us who can help.

Since Jake’s parents generally controlled his dinner and they were concerned about his health, this was the easiest meal to change. Instead of gluten-laden pastas, I asked them to feed him non-processed lean meats—with the occasional splurge of a rice-based pasta.

Fix #2 – Continue ferrous sulfate

Ferrous sulfate is an iron supplement. For now, it’s a good “in between” step — the “low-hanging fruit”, if you will.

You’ll notice that I didn’t push a ton of vegetables or fruits. Obviously, these are key to Jake’s health, but my goal was to transition him to a gluten-free and protein-rich diet before tackling the need for more vegetables.

As readers of this blog know, overloading clients with habits or food rules that they don’t feel confident they can follow leads to poor outcomes. Jake was very confident he could make the changes I’d suggested, especially knowing that his energy and muscle mass should improve as a result.

As a health care provider, I always check for confidence and readiness — and proceed from there, using simple, easy, do-able steps that clients are ready to tackle immediately. (If you find yourself stuck on making change, you might consider this using approach as well.)

I also kept him on his iron supplement so his anemia would resolve more quickly. When people feel better, they’re more likely to keep going with proposed changes.

The outcome

In just one month, Jake had already gained a bit of color. He had also gained a solid 4 pounds. Just from talking to him briefly I could tell he had more pep. He could bench 225 pounds 12 times (when his previous record was 8), he said. And when asked about his diet, he claimed it was going very well. He also said he’d found some gluten-free cookies that were delicious! I told him he could have them once or twice a week, since he was trying to gain weight.

Eventually Jake’s hemoglobin, hematocrit, and ferritin levels normalized completely. His performance in the gym and on the field improved immensely, not only from his increased endurance, but also his new-found muscles! And while it was tough for Jake to give up gluten-containing foods, with a little practice he learned to avoid them and to stick to his new diet.

Take away

One of the most important points to remember is that one symptom can have many causes. If you have an unexplained health problem, be creative and curious — explore multiple possibilities with a like-minded health care practitioner.

- Chronic fatigue is a single symptom with many causes, some physiologic, biochemical, and/or pathologic and some psychological (e.g. depression). In this case it was pathologic: iron deficiency. But it’s important to consider all possibilities before jumping to conclusions.

- Iron deficiency can be caused either by inadequate iron intake, blood loss, or malabsorption. Jake was eating iron, but not absorbing it. You are what you digest and not necessarily what you eat.

- Food intolerance is a common cause of nutrient deficiencies. Studies vary, but celiac disease occurs in about one of every hundred people in the U.S.. Unexplained anemias are sometimes undiagnosed celiac cases. If you’re concerned about any of these — or other health concerns — consult your health care provider.

Learn more

Want to get in the best shape of your life, and stay that way for good? Check out the following 5-day body transformation courses.

The best part? They're totally free.

To check out the free courses, just click one of the links below.

Share