Not all protein powders are created equal.

Some are definitely better than others.

But with hundreds, maybe even thousands, of options out there, it can be hard to know the right protein powder for you (or your clients).

After all, each person has unique goals, physiology, and preferences. So there’s no one single protein powder that’s best for everyone.

There may, however, be a best protein powder for you.

And we can help you find it.

In this complete guide to protein powder, you’ll learn:

- Why protein matters so much in the first place

- When it makes sense to include protein powder in your diet

- What to look for in protein powder

- How to choose the right protein powder for you (or help your client choose what’s right for them)

(If you want more insights on the hottest nutrition and health topics—and the world’s most effective coaching techniques—sign up for our FREE weekly newsletter, The Smartest Coach in the Room.)

If you’re looking for a quick answer to a specific question, you can jump directly to any of the information below:

- When should I drink protein shakes?

- Who should use protein powder?

- How much protein powder is too much?

- Is whey or casein better?

- What’s the difference between protein concentrate, protein isolate, and protein hydrolysate?

- How do different types of protein powder stack up against each other?

- What’s the best vegan protein powder?

- What should I do if my protein powder is causing digestive problems?

- How do I know if a protein powder is “clean” or safe?

- Is it important to choose an organic or grass-fed protein powder?

- What’s the best protein powder for weight loss / fat loss, muscle gain, or athletic performance?

Alright, let’s dive in.

+++

How much protein do I need?

Before you can find the protein powder that’s right for you (or your client), it helps to understand exactly why protein matters so much in the first place.

The main reason to use protein powder is to help you hit your protein goals.

(If you’re not sure how much you need, check out our handy Nutrition Calculator, which will give you a personalized recommendation for protein, carbohydrate, fat, and calories.)

Not getting enough protein can cause you to:

- lose muscle mass (which can cause a drop in your metabolism)

- have skin, hair, and nail problems

- heal more slowly if you get cuts or bruises

- experience mood swings

- be more likely to break bones

To be clear, though, this isn’t a concern for the majority of folks.

Most people eating the average Western diet aren’t protein deficient.

The bare minimum protein requirement is estimated to be 0.8 grams per kilogram (kg) of body weight, or 0.36 grams per pound. So at the absolute minimum, a 160-pound person needs about 58 grams of protein to prevent protein deficiency.

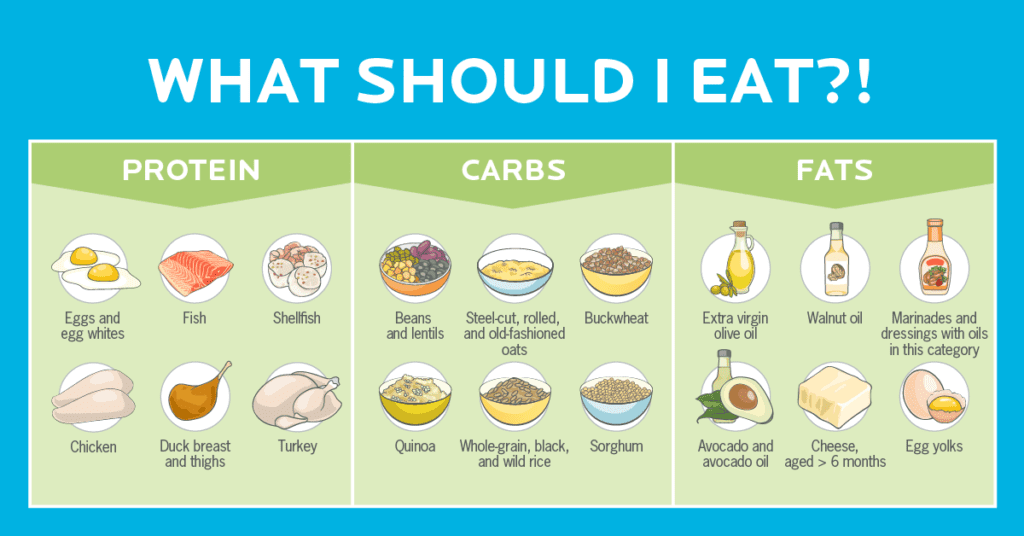

For reference, a palm of protein (using Precision Nutrition’s hand portion method) has about 20 to 30 grams of protein. So with 2 to 3 palms of protein—like chicken breast, tofu, Greek yogurt, or legumes—per day, you’d be set.

But eating the bare minimum of protein is different from eating an optimal amount of protein.

Generally, most active people can meet their optimal protein intake by eating 1 to 2 palms of protein at each meal.

Unless you have a specific medical reason to keep your protein intake low, most people will benefit from eating more protein.

Why? There are plenty of reasons, including:

- Appetite control: Eating a high-protein diet seems to improve satiety.1,2

- Weight and body composition management: Higher protein intakes may help people eat less when they’re trying to lose fat, increase the number of calories burned through digestion (the thermic effect of food), and retain muscle during fat loss.3

- Muscle growth or maintenance: Keeping protein levels high, combined with exercise, helps people gain vital muscle mass and hang onto it over time, especially as they age.4,5

- Better strength: Higher amounts of protein combined with exercise can also aid in strength gains.6

- Improved immune function: Proteins are the building blocks of antibodies, and serve several functions in the immune system. People who are protein-deficient are more susceptible to viral and bacterial infections.

- Faster exercise recovery: Higher protein intakes help to repair tissue damaged during exercise, as well as after injury.6

Protein from whole foods is ideal.

Why is protein from whole foods superior? Mainly, it’s because it comes packaged with other nutrients: vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, zoonutrients, and so on, depending on the source. (If you’re not sure which whole foods are good sources of protein, here’s a helpful guide.)

No supplement will be able to imitate those combinations exactly, nor their synergistic effects. And when foods are processed to create protein powder, certain nutrients may be stripped, and others may be added back in—which can sometimes be beneficial, and sometimes not.

Of course, protein powder does digest faster than whole foods. This would be an advantage if you were trying to quickly flood your muscles with protein after a workout.

This is an approach called nutrient timing—or eating certain nutrients at strategic times—and it was all the rage in the early 2000s. But as research advanced, the benefits of slamming a protein shake immediately after a workout proved less important than we once thought.

When should I drink protein shakes?

For most people, here’s what matters most: The amount of protein you consistently eat over the course of the day—not precisely when you eat it.

That’s not to say that nutrient timing is totally bogus. There’s certainly evidence that in some situations, protein (and carbohydrate) timing matters.7

But unless you’re an elite athlete or pursuing extreme fat loss or muscle gain, you don’t need to worry too much about when you get your protein. Read: Drink a protein shake when it makes the most sense in the context of your daily life. For example, you don’t have time for a good breakfast, it’s going to be several hours before your next meal, or it’s simply the most convenient time.

Why use protein powder?

While whole-food protein is best, it’s just not always possible to get all the protein you need from whole foods. Ultimately, there are two big reasons you might want to consider adding protein powder to your diet.

Reason #1: Convenience: In some cases, people just don’t have time to (or simply don’t want to) sit down and eat a whole-food meal. This might happen when a person is:

- Very busy with work, caregiving, or other responsibilities

- Aiming for a very high protein requirement and doesn’t have time/desire to eat that much whole-food protein

- Transitioning to a plant-based diet and still figuring out their preferred whole-food protein sources

- Trying to meet protein goals while traveling or with limited food options

Reason #2: Appetite: Other times, people don’t feel hungry enough to eat the amount of protein they need. This might happen when a person is:

- Trying to gain weight and is struggling to increase their intake

- Sick and has lost their desire to eat

- Aiming to improve athletic performance and recovery, but doesn’t feel hungry enough to meet their nutrient needs

These reasons are all completely legitimate.

But you don’t NEED protein powder to be healthy. It’s a supplement, not an essential food group.

How much protein powder is too much?

If you choose to use protein powder, 20-40 grams of protein per day (usually 1-2 scoops) from protein powder is a reasonable amount. For most people, 80 grams per day (about 3-4 scoops) is a good upper limit of supplemental protein intake.

This isn’t a hard and fast rule, just a general guideline.

The main reason: Getting more than 80 grams from protein powder is excessive for most people, as it displaces whole food sources that provide vitamins, minerals and other nutrients we need.

There are some exceptions, of course, such as for people who are struggling to gain weight.

How to choose a protein powder

If you’ve decided that protein powder is right for you (or your client), here are some considerations that’ll help you evaluate all your options and choose one that’s appropriate.

Question #1: What type of protein makes sense for you?

This is largely up to personal preference.

Besides ethical considerations—such as whether you prefer a plant or animal source—you might also want to think about food intolerances and sensitivities here. (More on those in a minute.)

Factor #1: Protein quality

For many people, the quality of the protein source is the highest priority. When it comes to assessing quality, there’s a lot of talk about complete versus incomplete proteins.

Proteins are made up of amino acids, which are sort of like different colored Legos. They can be put together in different ways to serve different purposes in the body.

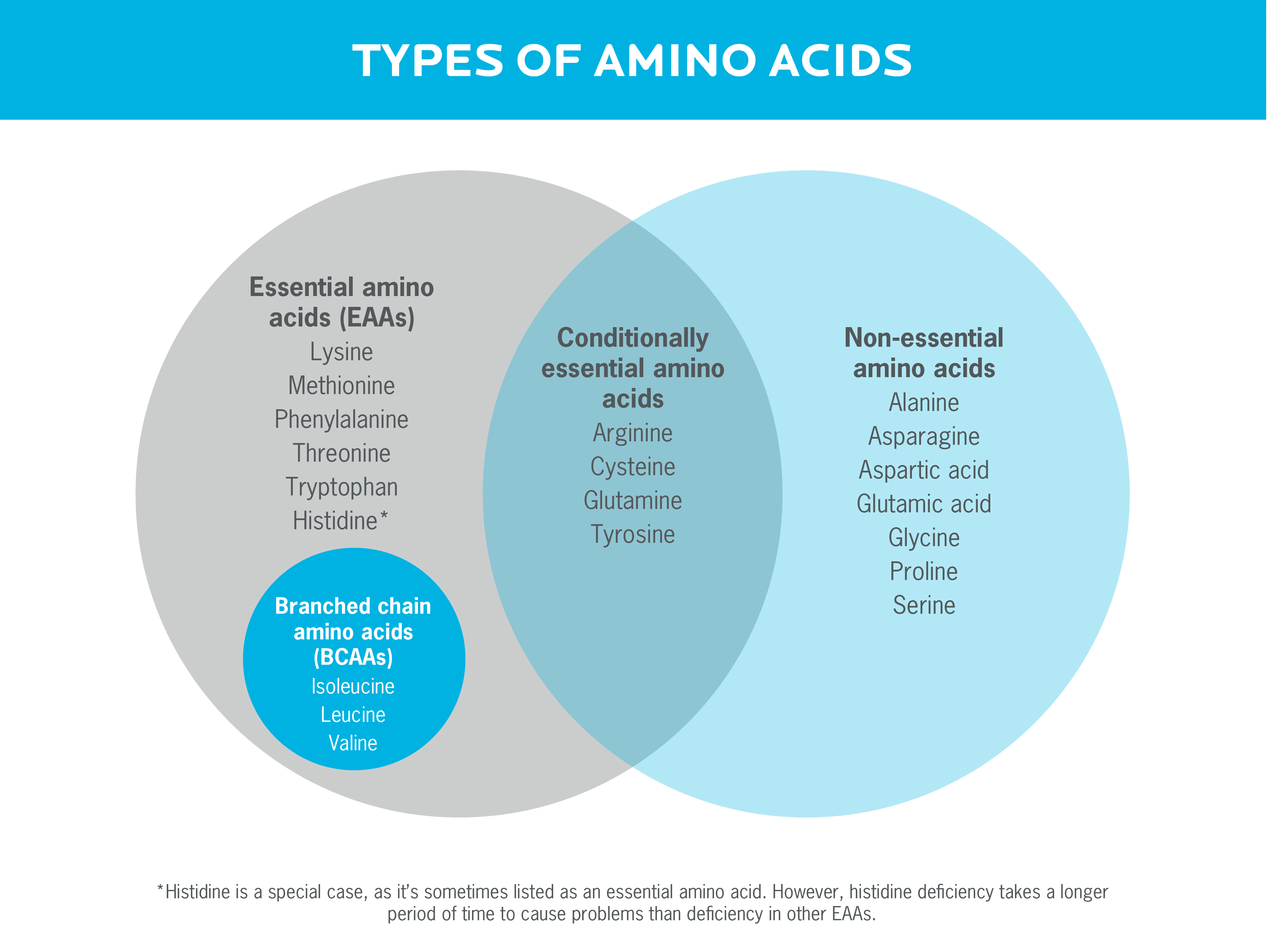

In all, your body uses 20 different amino acids.

Seven of those amino acids are non-essential amino acids. That’s because your body can create those on its own.

There are also four conditionally essential amino acids, which are ones your body can make, but not always. For example, your body might have a harder time making enough of them when you’re sick, or after hard athletic training.

The other nine amino acids are known as essential amino acids (EAAs). Your body can’t make these, so you have to get them from food.

This is important, because EAAs play key roles in building and repairing tissue—like muscle—but also in building hormones, enzymes, and neurotransmitters.

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), a subcategory of EAAs, are especially important for their role in muscle protein synthesis.

Muscle protein synthesis is the process your body uses to repair and build muscle after exercise. While muscle protein synthesis is much more complicated than just one amino acid, leucine plays an integral role in triggering the process, which makes it probably the most well-known BCAA.

A complete protein contains sufficient amounts of all nine EAAs. Incomplete proteins are lacking or low in one or more EAAs.

Here’s why we took the time to explain all of this: People sometimes worry they won’t get all their EAAs if they opt for plant-based protein sources.

That’s because many plant proteins are low in or lack specific amino acids.

For example, pea protein is low in the EAA methionine. But you can still meet your overall protein needs as long as you eat a variety of other plant protein sources throughout the day. For example, tofu, brazil nuts, and white beans are all good sources of methionine.

Also: Some plant-based proteins—like soy protein and a pea/rice blend—offer a full EAA profile.

Oftentimes, supplement companies create blends of different plant-based proteins to ensure all EAAs are included in optimal levels.

Let’s take a deeper look: protein digestibility

Beyond complete and incomplete proteins, there are several other methods scientists use to assess protein quality.

The main measures scientists look at are digestibility and bioavailability, or how well your body is able to utilize a given type of protein. This can vary depending on a protein’s amino acid makeup, along with other factors.

The Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) is a measure of how much of a given protein is truly digestible. The highest possible score is 1.0. And the higher the score, the higher the quality of protein. (Read this if you want to know more about how PDCAAS is calculated.)

There’s another scale that some prefer, as it may provide a more accurate picture of bioavailability: The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS). Similar to the PDCAAS, the higher the score, the higher-quality the protein.8

Here’s how several common protein powders stack up according to these scales:

| Protein type9,10,11 | PDCAAS | DIAAS |

|---|---|---|

| Whey protein isolate | 1.00 | 1.09 |

| Whey protein concentrate | 1.00 | 0.983 |

| Milk protein concentrate | 1.00 | 1.18 |

| Micellar casein | 1.00 | 1.46 |

| Egg white protein | 1.00 | 1.13 |

| Hydrolyzed collagen & beef protein isolate | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bone broth protein | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Soy protein concentrate | 0.99 | 0.92 |

| Soy protein isolate | 0.98 | 0.90 |

| Pea protein concentrate | 0.89 | 0.82 |

| Rice protein concentrate | 0.37 | 0.42 |

| Hemp protein | 0.63 | N/A* |

| Rice/pea blend | 1.00** | N/A* |

*Because DIAAS is a newer measure of protein quality, some values are unknown.

**A 70:30 blend of pea and rice protein closely resembles whey protein, but ratios vary across manufacturers.

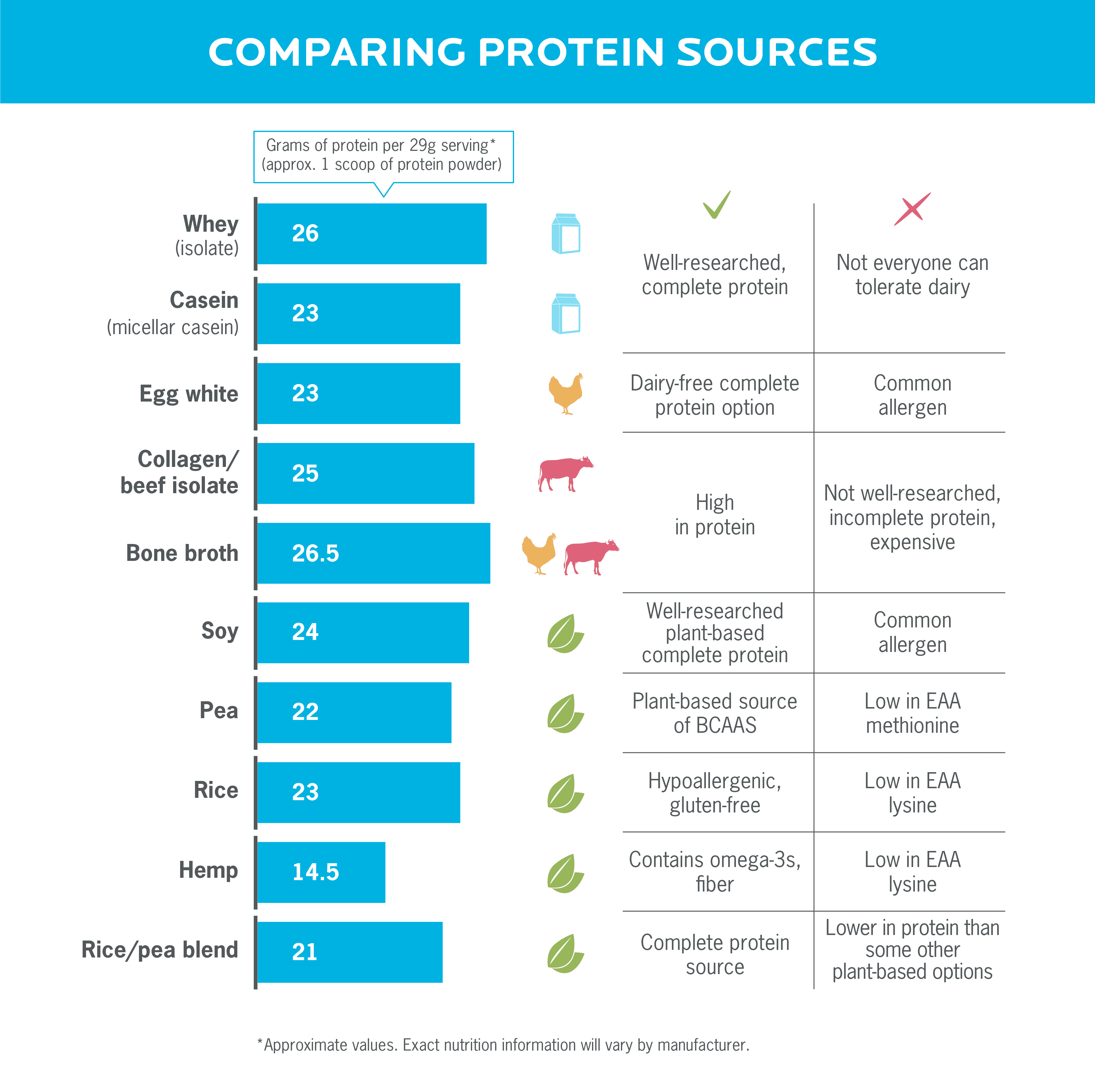

As you can see, animal proteins (except for collagen and bone broth protein) tend to score higher than plant proteins.

Similar to choosing protein made from incomplete protein sources, just because a protein powder doesn’t have a PDCAAS of 1.0 or has a lower DIAAS doesn’t mean it’s a poor option. It can still be beneficial as long as you get a variety of protein sources throughout the day.

Factor #2: Plant-based vs. animal protein

Animal protein options can be divided into two categories: milk-based and other animal protein sources.

Milk-based protein powders

The most popular and well-studied protein powders are made from milk. They’re all complete sources of protein.

Whey is usually recommended for post-workout shakes because it’s an incredibly high-quality protein that’s fast-digesting and rich in BCAAs. You’ll commonly see whey protein in concentrate, isolate, and hydrolyzed formulas. (More on what those mean in a moment—or you can jump right to our section on protein processing.)

Casein is often touted as the best type of protein powder to have before bed, since it digests more slowly. You’ll find it mostly in two forms: micellar casein (an isolate) and hydrolyzed casein. Since hydrolyzed casein is more processed and theoretically digests faster, it sort of defeats the purpose of opting for a slow-digesting protein.

Milk protein blends usually include both whey and casein and are marketed as the “best of both worlds.” The reason: They provide both fast- and slow-digesting protein.

Usually, you’ll see them on the label as milk protein concentrate or milk protein isolate. You might also see them listed separately, for instance: whey protein isolate and micellar casein.

Some brands also sell mixtures of concentrate and isolate of the same type of protein. For example, you might see both whey concentrate and whey isolate in the ingredients list.

While this may be marketed as an advantage, it’s largely a cost-saving measure by the manufacturer. (Whey isolate is more expensive to produce than concentrate.) There’s no data to support the claim that this formulation provides a benefit.

If you’re choosing between whey and casein: Select whichever one you prefer, or go for a blend.

Both are well-studied, meaning they’re reliable choices. Again, it’s your total protein intake across the day that matters most. For most people, the differences in the rates of digestion or absorption aren’t likely to be an important factor.

Of course, if you’re allergic to dairy, these won’t be good options for you. If you’re sensitive to or intolerant of certain dairy products, you may find that you can tolerate whey but not casein, or vice versa.

Other animal protein powders

For those who can’t or prefer not to use dairy products, there are several other types of animal-derived protein powder.

Egg white protein is often a good option for those who prefer an ovo-vegetarian (milk-free) source of complete protein.

Collagen is very popular right now as a skin, joint, bone, and gut health supplement. Collagen peptides, the most common form of collagen in supplements, are usually derived from bovine hide or fish. Some people also use it to boost their protein intake, and there are a few collagen powders marketed specifically as protein supplements.

This is somewhat ironic because until the early 2010s, collagen was considered a “junk” protein. This is partially because collagen is not a source of complete protein.12 It also hasn’t been well-studied as a protein supplement.

Collagen may have some benefits. In particular, type II collagen may support joint health when taken with vitamin C.13 But as a protein source, it’s not ideal. Quality varies, and there are some concerns about heavy metal contamination. So it’s especially important to look for third-party tested options.

Meat-based powders are often derived from beef, but they usually have an amino acid profile similar to collagen. That means they’re generally incomplete, lower-quality proteins. On the other hand, some research has shown that beef protein isolate is just as effective as whey protein powders for increasing lean body mass.14,15 However, more research is needed.

Bone broth protein is made by cooking bones, tendons, and ligaments under high pressure to create a broth. Then, it’s concentrated into a powder. Much of the protein in bone broth is from collagen. So, similar to collagen peptides, it’s not a complete source of protein.

Bone broth powder may be helpful for increasing your protein intake if you can’t have common allergens like dairy and soy, but it’s not ideal for use as a protein powder. This is especially true because bone broth protein tends to be expensive, and it hasn’t been well-studied for use as a protein supplement.

Plant-based protein powders

Not all plant-based proteins are complete proteins. We’re going to share which ones are complete and incomplete for your information, but just a friendly reminder: As long as you eat a varied diet with a mix of different protein sources, you’ll get all the amino acids you need.

Soy protein is effective for promoting muscle growth, and it’s also a complete protein. In fact, research shows soy protein supplementation produces similar gains in both strength and lean body mass as whey protein in response to resistance training.16

It’s also been the subject of much controversy, particularly when it comes to hormonal health. But the body of research shows that soy foods and isoflavone (bioactive compounds found in soy) supplements have no effect on testosterone in men.17

Evidence also shows that soy doesn’t increase risk of breast cancer in women.18 And while more research is needed in this area, it also seems that soy doesn’t have a harmful effect on thyroid health, either.19 (If you want to dig deeper into soy, here’s more info.)

Soy is a fairly common allergen, so that may also factor into your decision.

Pea protein is highly digestible, hypo-allergenic, and usually inexpensive. It’s rich in amino acids lysine, arginine, and glutamine. Although as we mentioned earlier, it’s low in EAA methionine, so it’s not a complete protein.20

Rice protein is also a good hypo-allergenic protein choice, and tends to be relatively inexpensive. It’s low in amino acid lysine, so it’s not a complete protein source.20

Hemp protein powder is made by grinding up hemp seeds, making it a great whole-food choice. Because of this, it’s high in fiber and a source of omega-3 fats. But like rice protein, hemp is low in lysine, so it’s an incomplete protein.11

Blends are common among plant-based protein powders. Often, they’re used to create a more robust amino acid profile, since different protein sources contain various levels of each amino acid. For example, rice and pea protein are frequently combined.

Factor #3: Processing method and quality

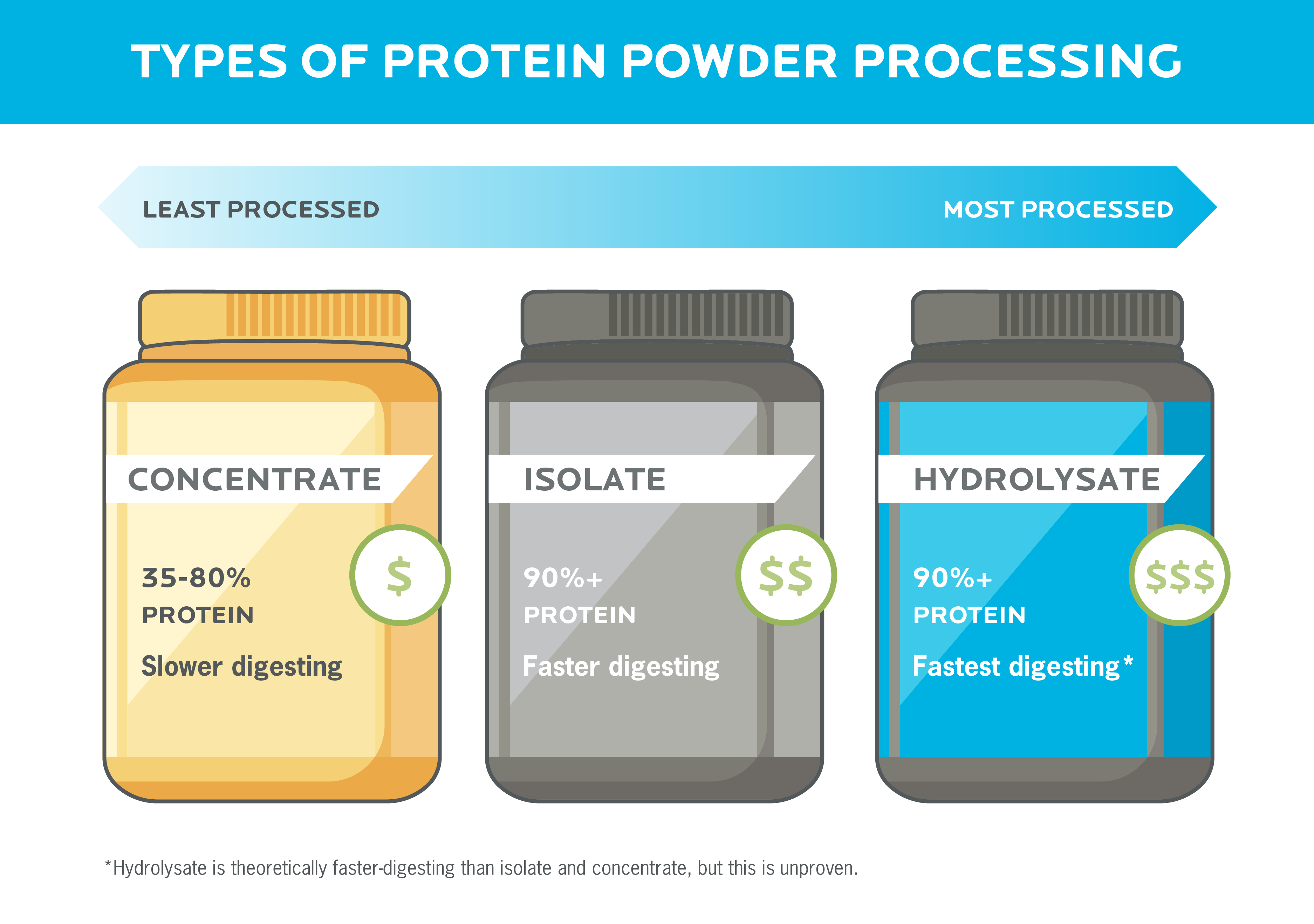

Protein powders are created through various processing methods and come in several different forms, including concentrates, isolates, and hydrolysates.

Let’s look at each processing method in more depth.

Concentrates: Protein is extracted from animal or plant-based foods by using high heat and acid or enzymes. Concentrates are the least processed and can be 35 to 80 percent protein by weight.21 A protein percentage of 70 to 80 percent is generally the most common (though this can be lower in plant proteins in particular).

The remaining percentage is made up of carbohydrates and fats. So if you don’t mind having some additional calories from non-protein sources, protein concentrate could be a good option for you.

Isolates: Protein isolates go through an additional filtration process, which reduces the amount of fat and carbohydrates, leaving 90 percent or more protein by weight. This makes them slightly faster-digesting, though there isn’t evidence that this results in improved recovery, muscle growth, or fat loss.

Since isolates usually contain a bit less fat and carbohydrates than concentrates, they might be a slightly better choice for those who are carefully limiting their fat or carb intake, or who are willing to pay more just for potential extra benefit, even if not proven.

Whey, casein, and milk protein isolates may also be slightly better for people with lactose intolerance, since more processing removes much of the lactose.

Protein hydrolysates: To create this product, protein undergoes additional processing with heat, enzymes, or acid, which further breaks apart the protein chains into shorter peptides.

The idea is that this extra processing and the resulting shorter chains makes protein hydrolysates even more easily digested and absorbed. So they’re usually marketed to people who want to gain muscle and are drinking protein shakes around their workouts.

While this process makes sense theoretically, the evidence is far from clear that hydrolysates are better than isolates for this purpose.

However, because hydrolysates are essentially pre-digested due to their processing—there’s even less lactose in them—they can be easier on the GI tract for some people.

There are a couple of downsides to hydrolysates, though. First, they tend to have a bitter taste that generally requires a significant amount of added sweeteners and/or sugar to mask.

Second, whey protein concentrates and “non-ionized” isolates retain bioactive microfractions that may improve digestion, mood, and immune function. Whey hydrolysates (and “ionized isolates”) don’t contain these bioactive microfractions. (Casein appears to have some of these bioactive microfractions, too, but is less well studied in this area.)

Price may also be a drawback of hydrolysates, depending on your budget. Typically, the more processed a protein powder is, the more expensive it is.

Factor #4: Intolerances and sensitivities

If you have a known food intolerance or sensitivity, you’ll want to avoid protein powders containing those ingredients. For example, if you’re intolerant to eggs and dairy, you’ll likely be better off with a plant-based protein powder.

If you’re prone to digestive issues, more processed options, such as isolates and hydrolysates, are usually easier on the stomach.

It’s also not uncommon to experience digestive upset after using a new protein powder. This can happen for a variety of reasons. Use the below checklist to get to the bottom of it.

- Ingredients: The protein powder you’ve chosen might contain ingredients you’re sensitive to, or be processed in a way that doesn’t agree with you. For this reason, it’s a good idea to check out the ingredient label (we’ll explain how below). You may need to try a few different options before finding the right protein powder for you.

- Overall diet: Your body’s reaction to a protein powder might also depend on what else you’ve eaten that day. For example, many people can tolerate a certain amount of lactose, but once they get over their threshold, they experience symptoms. If your protein powder contains lactose, it could be pushing you over the edge.

- Amount: It can also be an issue of quantity. Men are sometimes told to use two scoops of protein powder instead of one. For some individuals, this may simply be too much at once for their digestive tract to handle optimally. Others might concoct 1500-calorie shakes in an effort to gain weight. Most people would have a hard time digesting that. So it may help to experiment with smaller amounts.

- Speed: Drinking too fast can cause you to swallow excess air, which can upset your stomach. And if you drink a shake with lots of different ingredients, your GI tract needs time to process them. Slow down, and you may find it’s easier to digest.

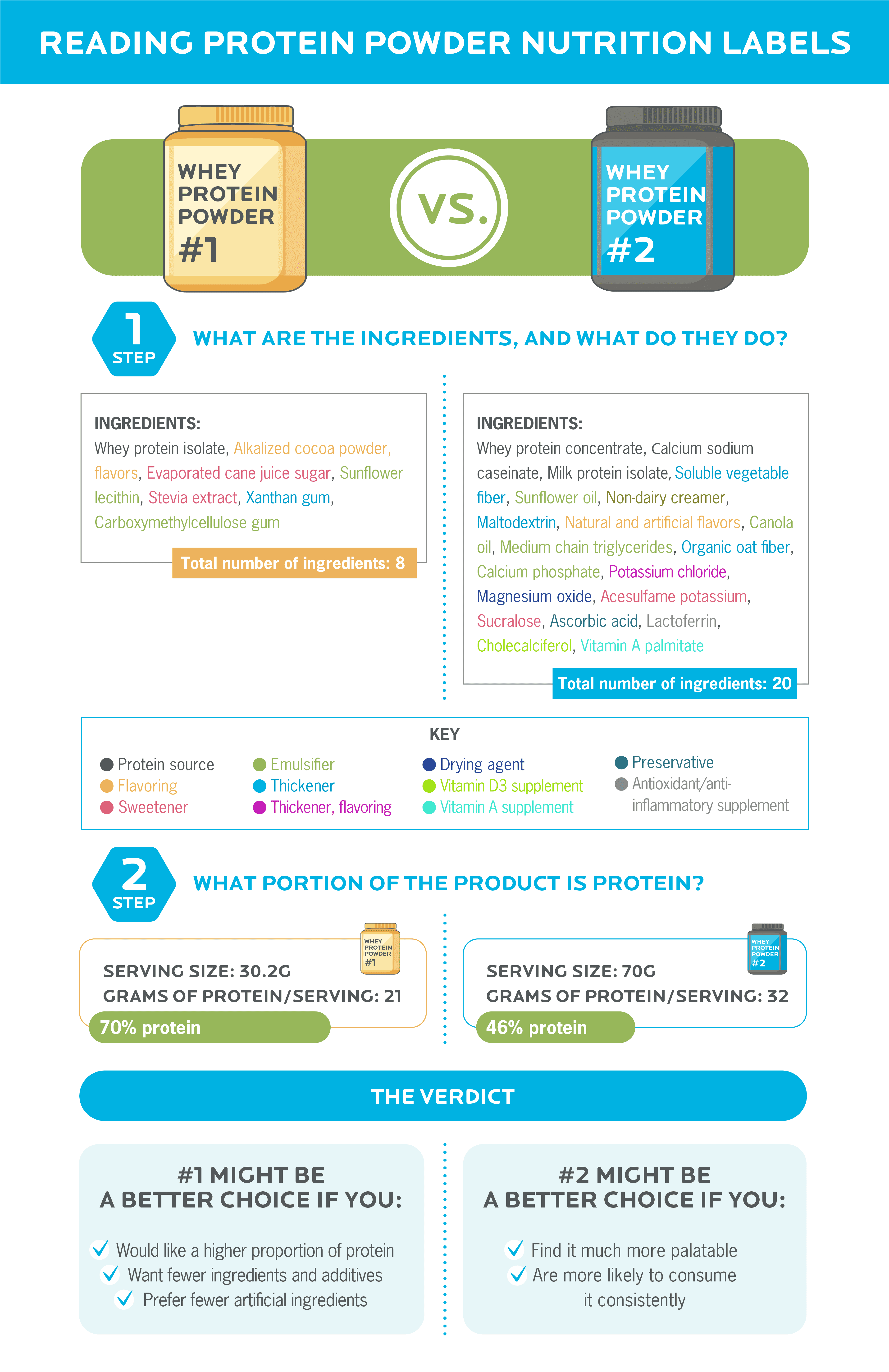

Question #2: What other ingredients are in the protein powder?

While sweeteners, flavoring, and thickeners are common in protein powders, some contain more than others.

There are exceptions, but you generally want to look for protein powders with fewer ingredients. That said, guidelines like “look for foods with fewer than five ingredients” don’t necessarily apply to protein powders.

Here’s a look at the most common ingredients in protein powders, plus how to make sense of them.

Protein

Because ingredients are listed by weight, the protein source should be the first item listed. Usually, it’ll include the name of the protein source (milk, whey, casein, soy, hemp) and the processing method (concentrate, isolate, hydrolysate). For whole-food protein powders, you might see something like “hemp seed powder.”

Sweeteners

Flavored protein powders will include some type of sweetener. Most often, you’ll see:

- Nutritive sweeteners, like honey, maple syrup, brown rice syrup, coconut sugar, cane sugar, molasses, and agave. You’ll be able to tell right away if a product has nutritive or “natural” sweeteners by looking at the sugar content. Ideally, choose a protein powder that has less than 5 grams of sugar per serving (especially if your goal is fat loss or better overall health).

- Non-nutritive / high-intensity sweeteners, like sucralose, aspartame, saccharin, and acesulfame potassium. These are the same type of sweeteners found in diet soda, so you won’t be able to tell if a protein powder contains them from looking at the sugar content; you’ll have to check the ingredient label.

According to the FDA, stevia and monk fruit extract are non-nutritive sweeteners, though they are sometimes listed and marketed as “natural” sweeteners.22 This can be frustrating for consumers, because supplement companies sometimes advertise that their products have “no artificial sweeteners,” yet they contain monk fruit extract or stevia. Since the FDA doesn’t regulate this term, it’s important to check the ingredients list if you prefer to avoid all non-nutritive sweeteners.

- Sugar alcohols, like sorbitol, maltitol, and erythritol. These are another non-caloric option and are made up of sugar and alcohol molecules—although not the kind of alcohol that causes intoxication. Because sugar alcohols act like dietary fiber in the body, people who are sensitive to FODMAPs may find they cause digestive upset.

- Refined sugars, like sucrose and high-fructose corn-syrup, are less common in protein powders. But if you’re watching your refined sugar intake, it may be worth checking to see if they’re on the ingredients list.

Flavoring

Flavored protein powders will also contain flavoring agents, which are sometimes listed as specific ingredients. Most often, they’re represented more vaguely on the label as flavors, artificial flavors, or natural flavors.

Artificial flavors are generally recognized as safe when consumed at the intended levels, such as the small amounts found in protein powders.23

The only exception to this would be if you have any allergy to a specific ingredient. If a natural flavor contains one or more of the eight major food allergens, it must be listed in the ingredients. But if you have an allergy that isn’t one of the eight major allergens, it’s important to know that it does not have to be listed on the label.

Thickening agents

Protein powders often include substances that provide bulk for a thicker protein shake. These generally include psyllium husk, dextrins, xanthan gum/guar gum, and inulin.

These are safe in small amounts, so while some people may prefer protein powders without them, seeing thickening agents on the ingredient label shouldn’t cause concern.

Emulsifiers and anti-clumping ingredients

Whole food protein powders usually clump more, which makes them less ideal for mixing by hand. That’s often because they lack anti-clumping ingredients and emulsifiers (which provide a creamy mouthfeel) like carrageenan, lecithins, carboxymethylcellulose, and silicon dioxide.

Similar to thickening agents, small amounts of these ingredients have been shown to be safe.

Vegetable oils may also be added for a creamier texture. They are safe as long as they aren’t hydrogenated or partially hydrogenated oils (aka trans fats). You want to avoid trans fats as much as possible since they can have adverse health effects, such as increased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

Certain thickeners and anti-clumping ingredients also double as preservatives to help protein powders stay shelf-stable.

Additional supplements

Some protein powders include added supplements, such as creatine, extra BCAAs, omega-3 and 6 fatty acids, digestive enzymes, and probiotics.

These are often touted by marketers as a value-add. But we don’t know how well these nutrients work when formulated along with protein powder.

What’s more, manufacturers often include these additional supplements in inadequate amounts. So it’s generally better to seek out an additional supplement rather than looking for it in your protein powder.

For example, if you want to try creatine, it’s better to take it as a separately-formulated supplement. (Although it would be fine to consume them together in the same shake.)

Purity and quality: How to know if a protein powder is “clean” and safe

In laboratory tests, some protein powders have been shown to be contaminated with heavy metals. With this information in mind, it’s natural to wonder, are protein powders safe?

Depending on where you live, supplements may or may not be a regulated industry. So it’s important to understand the supplement regulations in your country or region.

For example, while regulations are much more stringent in Canada and Europe, in the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t test the effectiveness, safety, or purity of nutritional supplements.

This means it’s possible what’s on the ingredient label doesn’t match up with what’s in the supplement.

Most supplement companies aren’t selling bogus supplements on purpose (although it happens). The main concern is that supplements could be contaminated with other substances like heavy metals (such as lead) or harmful chemicals, and in many cases, no one would know—not even the companies producing them.

It’s also important for competing athletes to know exactly what’s in their supplements, including protein powder, on the off-chance it might contain a banned substance. No protein supplement is worth a disqualification after months of training.

Because of the varying levels of regulation, it’s a good idea to choose third-party tested supplements when possible—particularly if you live somewhere with less pre-market testing.

NSF International’s Certified for Sport does the most comprehensive third-party certification/testing of nutritional supplements for sport. In fact, here at PN, we advise our coaches and clients—even those who aren’t necessarily athletes—to use supplements that have been certified by NSF because of their high standards.

USP is also a reputable third-party tester.

Another organization, LGC Group, runs an independent drug surveillance laboratory providing doping control and banned substance testing for supplements through the Informed-Sport and Informed-Choice programs.

Products that have been tested by these organizations usually clearly state this on their websites and often on their product packaging. These organizations also have databases of approved supplements to choose from.

An important note: Third-party tested protein powders may be more expensive. This is partially because the testing process is quite expensive. At the same time, investing in third-party testing shows that a supplement company is committed to protecting the health and reputation of their customers.

While it’s preferable to opt for a validated supplement, if third-party tested options are outside of your price range, another option is to visit ConsumerLab or LabDoor. These websites are devoted to reviewing purity and label claims for a variety of nutritional supplements on the market today.

Other ingredient concerns

Much like other foods and supplements, protein powders are often marketed with buzzwords like “organic” and “grass-fed.” When choosing a protein supplement, it’s important to understand what these labels truly mean, so you can decide whether or not they’re important to you.

People often prefer organic products to non-organic ones because of concerns about pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, genetic engineering, and chemical fertilizers. (You can read more about organic foods and standards here.)

The most recent evidence suggests there may be potential health benefits with consumption of organic foods. However, it’s still too early to conclude that organic food is safer and or more nutritious than conventional food.24,25

So ultimately, whether or not you choose organic comes down to a matter of personal preference.

If you do opt for an organic protein powder, look for the official organic seal of your country or region.

For certain types of protein, such as whey, casein, and beef isolate, being grass-fed is also seen as a plus. Grass-fed cattle only eat grass and forage, with the exception of milk prior to weaning. Certified grass-fed animals cannot be fed grain or grain byproducts and must have continuous access to pasture.26

Grass-fed meats are often touted for their health benefits, as they contain more omega-3 fatty acids than non-grass-fed meats, so the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids is superior. But because there’s very little fat in most protein powders, this benefit doesn’t necessarily translate from whole food to protein powder.

Also, grass-fed products may still be treated with growth hormone and antibiotics, so if that’s a concern, opting for a certified organic protein powder is a better option.

Finally, if the health and treatment of the animals themselves is important to you, choosing a product that comes from a certified humane producer is your best bet. A product being marked grass-fed and/or antibiotic-free doesn’t automatically mean it was produced humanely.

Question #3: How does protein powder fit into your diet?

Lastly, you’ll want to think about how your protein powder fits into the overall context of your diet.

Be mindful of your goal.

Here’s what you might want to consider depending on your goals, and what you’re hoping to get out of your protein shake.

► Weight loss / fat loss: If you’re looking to lose fat, pay attention to the protein-to-calorie ratio of your protein powder. The best protein powder for weight loss will be higher in protein and lower in carbs and fat, since the latter two macronutrients will be more satisfying coming from whole foods.

► Muscle gain: To put on muscle, look for a protein powder with a high protein-to-calorie ratio, as the main goal is to consume adequate overall protein. If you’re struggling to get adequate overall calories, a protein powder that’s also rich in carbohydrates can be helpful around workouts.

► Weight gain: For those who are looking to gain any type of weight—most often this is due to illness that reduces appetite—consider powders that are high in protein, carbohydrates, and fat. Particularly if you won’t be getting much other nutrition, it’s important to get all three.

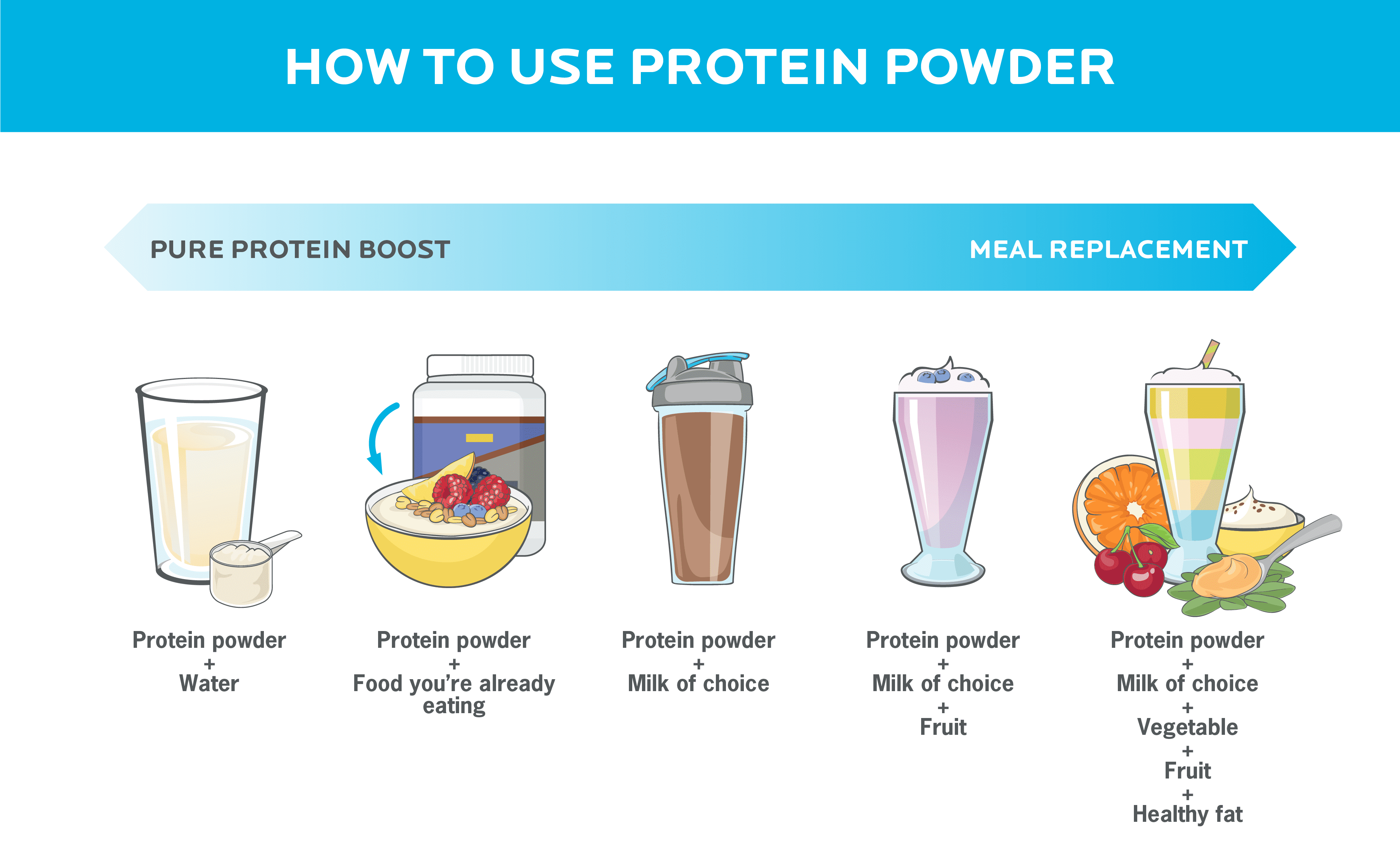

► Meal replacement: If you plan to use your protein shake as a meal replacement, it’s important to get some other nutrients in there, too. While there are protein powders that come with additional nutrients built-in, we recommend making your own Super Shake instead by incorporating fruit, vegetables, a source of healthy fats, and possibly more. That way, you get all the whole-food benefits of these ingredients.

► Recovery/athletic performance: There are a variety of suggested ratios of carbohydrate and protein intake post-exercise to maximize recovery, but there isn’t much evidence showing any particular ratio is optimal. A protein powder with a 2:1 or 3:1 carbohydrate-to-protein ratio might be beneficial, but ultimately your total macronutrient and calorie intake for the day is the most important determining factor in athletic recovery.6

If you’re an athlete competing in multiple events in one day, consuming a beverage with 30 to 45 grams of carbs, 15 grams of protein, and electrolytes (sodium and potassium) in 600 mL (20 ounces) water for every hour of activity could help with recovery and performance.

Consider how much taste matters to you.

It’s important to choose a protein powder that you’re likely to consume consistently. Enjoying the way it tastes is one way to help ensure that. Of course, the best-tasting protein powder option varies from person to person.

Factors you might want to be mindful of when deciding on a protein powder:

Mixability and texture

Mesh count refers to how fine a protein powder is, which can impact how easily it will mix by hand in a shaker bottle. You won’t be able to see this information on the label, but sometimes you can tell by looking at the powder or touching it.

Plant-based protein powders tend to have a grittier or chalkier texture, which means they often taste better when blended using an electric blender (rather than a shaker cup). Blending with a creamier liquid, such as plant milk, or adding higher-fat items like yogurt and nut butters to your shake can also help smooth out a chalky protein powder. (For ideas on how to make your protein powder taste better, try these flavorful smoothie recipes.)

More highly-processed powders, such as isolates and hydrolysates, are more likely to have a smoother texture.

Flavor

Some people are especially sensitive to the taste of artificial flavors and non-nutritive sweeteners. If that describes you, look for a protein powder made with nutritive sweeteners and/or natural flavors.

Unflavored protein powder may also be a good option if you don’t like artificial flavors, or simply prefer the flavor of whole foods. You can use unflavored protein powder in a variety of ways including:

- Blended in Super Shakes with other flavorful ingredients

- Baked into muffins, cookies, and even granola bars

- Stirred into oatmeal, pudding, soups, and pancake batter

Flavored protein powders also work in many of these non-shake options. (Try this recipe for homemade protein bars that can be made with flavored or unflavored protein powder.)

As we already mentioned, you may have to experiment with a few different flavors and brands before finding the right protein powder for you.

Before you commit to a large package, try to get a sample pack of the protein powder. Larger nutrition supplement companies usually offer these.

If the powder you want to try isn’t available in a single-serve pack, you might be able to get a sample from a local supplement shop, if you ask nicely.

Protein powder isn’t a nutrition essential.

But it is a useful tool.

And here at Precision Nutrition, we’re all about picking the right tool for the job.

So if you’re struggling to meet your protein goals—whether because of convenience or appetite—then protein powder may be exactly what you need.

It’s worth noting you may have to do some experimenting before you find the right one. Our advice: pick one and stick with it for two weeks, and treat this time period like an experiment.

Pay attention to how you feel, and note any changes. Do you have more energy than before? Are you experiencing new, weird digestive issues? Are you feeling less hungry in the hours after your workout? Consider how these changes might be getting you closer to—or further away from—your goals.

If the changes are positive, you may have found your winner. If not, try a different flavor, brand or type of protein.

In the end, choosing the best protein powder for you ultimately comes down to asking the right questions, then experimenting with different options.

And that advice? It’s solid not just for picking a protein powder, but pretty much any decision in the world of nutrition.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

You can help people build sustainable nutrition and lifestyle habits that will significantly improve their physical and mental health—while you make a great living doing what you love. We'll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification. (You can enroll now at a big discount.)

Share