Special operations selection courses are designed to weed people out.

In the Navy, the screening test to just qualify for these courses has about a 90 percent failure rate.

From there, anywhere between 60 to 90 percent of candidates don’t make it through the course itself.

Those who do make it, more than anything else, display the ability to just keep going through a painfully discouraging process.

They face a daily onslaught of being pushed to their limits: hypothermia, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and sand-in-your-everything.

Yet some persevere and ultimately graduate.

(If you want to see the author discuss this article in even more detail, check out the video below. If not, simply scroll over the video player or click here to jump to the next section.)

PN coach roundtable: Robin Beier talks about how to stay motivated with Craig Weller.

How do you stay motivated through something that’s devised to make you feel terrible, day after day?

The answer is more complex than you might imagine.

Contrary to what most people think, accomplishing big-picture dreams has very little to do with feeling motivated from moment to moment.

And it has even less to do with being good at something from the start.

This is true whether you’re trying to get through a grueling selection course, a fat loss journey, a career change, or a marathon training plan.

Right after graduating high school in small-town South Dakota, I joined the Navy.

I volunteered for a Special Operations unit. But when I left for boot camp, I didn’t know how to swim. As you can imagine, swimming is a pretty important skill in Naval Special Operations.

My odds of success were near zero.

I learned to swim by taking the screening test, failing it, and going to an hour of stroke development to practice. I passed that test by seven seconds on my third and final attempt.

Then began two and half years of suffering.

I spent 16 months in preparatory training, and was two weeks from graduating my first Special Warfare Combatant Crewmember (SWCC) selection course when I failed a timed swim. Because I was so far along, I was given the option of repeating the entire course.

But before starting over, I spent four months in a BUD/S (Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL) development program. Then I went through SWCC selection again. This time, I graduated.

Along the way, I watched thousands of people—nearly all better swimmers than me—fail out or quit. During this process, I learned the characteristics that help someone succeed. (I also learned the factors that lead to failure.)

What I discovered surprised me: Initial talent was only a small piece of the picture. And physical fitness? It was only one of many factors.

The best athletes often quit early and reliably.

As it turns out, where you start is far less important than where you’re willing to go.

One of the main differences between those who succeeded and those who didn’t was the word “yet.”

“I’m not strong enough. Yet.”

“I don’t know how to do this. Yet.”

“I can’t handle this. Yet.”

Like everyone else in the program, the people who graduated struggled plenty, suffered setbacks, and had bad days. But the difference maker? They were also the ones who managed to consistently do a difficult, discouraging thing for a long time in order to finally reach a long-term goal.

Which then leads us to ask, How?

Here’s the secret:

It wasn’t motivation that got them there.

Motivation is what gets you started. Almost everything after that is just doing what needs to be done in the moment… until you eventually get where you want to be.

Motivation may return at some point—but it’s never guaranteed.

7 ways to keep moving forward when you don’t feel motivated.

Doing the right thing when the right thing is hard isn’t limited to the tiny, bizarre world of special operations. It’s a universal concept.

A new parent getting out of bed at 3 a.m. to soothe a screaming baby for the fifth night in a row isn’t enthusiastic about it.

The entrepreneur spending their Friday night combing through bank statements and receipts isn’t madly in love with do-it-yourself accounting.

The athlete putting in 5 a.m. workouts doesn’t hate warm blankets and sleep.

But if not motivation, then what helps people do the hard stuff?

People who consistently do the hard thing have several core ideals and practices in common. Here’s how you can adopt them yourself.

#1: Have a deep reason.

When I had my lowest points in training, I fell back to a mental image of my Dad’s snow boots sitting by our front door.

Growing up, we had two cars. My mom was a paramedic and needed one of them. My dad chose to walk to work in the snow every morning so my siblings and I could use the other car to get to school.

The mental image of his snow boots represented the countless little sacrifices my parents made for me over the years. Knowing all these sacrifices gave me a deep reason to persevere: I didn’t ever want to have to tell my parents I’d given up because it was too hard.

A deeper reason is the fail-safe that keeps you going when you’ve got nothing else left in your tank.

This mental image has to be uncomplicated, because when you’re hitting rock-bottom from stress, you won’t have the capacity to sort through complex, abstract concepts. You need one image that cuts directly to your core, no matter how tired you are.

There’s no surefire way to find that image. Each of our inner worlds is too complicated for this to be an easy exercise. But for a place to start, ask yourself:

- When you have your biggest successes or failures, who do you want to talk to about them? Why?

- Think back to a time when someone truly cared about and helped you. Imagine that person watching you in one of your most difficult moments. What do you want them to see?

#2: Find meaning being uncomfortable.

The Latin root of the word passion is patior, which means to suffer or endure. This is where phrases like The Passion of the Christ got their name. Eventually, the word came to mean not just the suffering itself, but the thing that sustains you while suffering.

When we think of people who consistently overcome hardships in order to achieve a big goal, patior is what we see. And it’s easy for us to mistake patior for motivation.

It’s not that these people feel like making small daily sacrifices and trading short-term comfort for long-term happiness. It’s that they have a purpose for doing so. Their suffering has meaning.

In order to keep working towards something big, this purpose needs to be a frequent, daily presence in your mind.

In Okinawa, where people have the longest, healthiest lifespans in the world, they call this ikigai: Their reason for living.

When surveyed, most Okinawans know their ikigai immediately, just as clearly as you know what you had for lunch.

The ikigai of one 102-year-old karate master was to teach his martial art. For a 100-year-old fisherman, it was bringing fish back to his family three days a week. A 102-year-old woman named spending time with her great-great-granddaughter as her ikigai.

This is different from the deepest reason I described earlier. That deep reason is something rooted in your past, that helps to drive you forward and, as the ancient Greeks used to say, “live as though all of your ancestors were living again through you.”

Your ikigai is more about being and becoming. It’s present and future. It’s defining, through your actions, the words that will be on your tombstone.

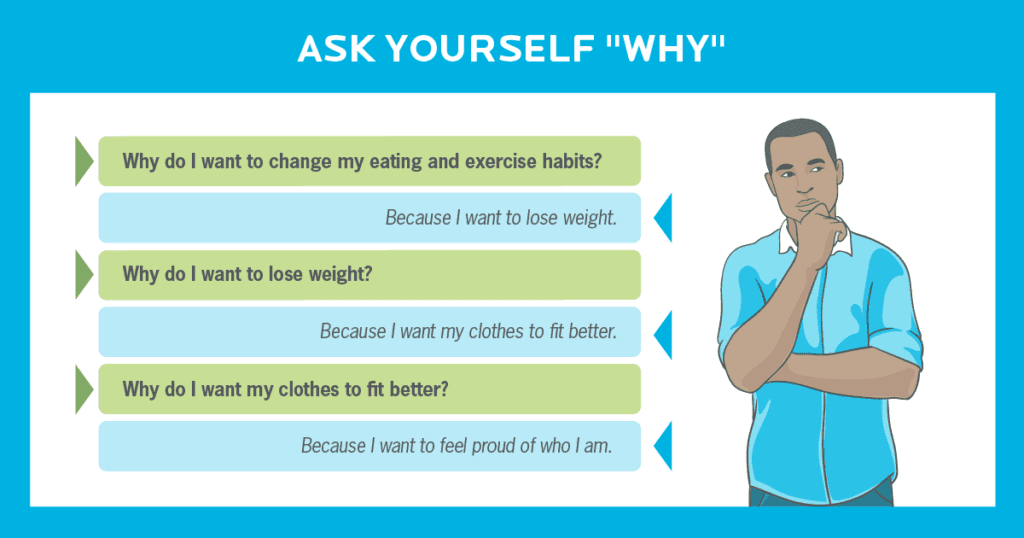

Here at Precision Nutrition, we use an exercise called the “5 Whys” to help people identify their meaning and purpose.

Take some time to go through this exercise using this worksheet. It’ll help you clarify your values, define your own ikigai, and identify where in life you derive the most meaning.

#3: Prioritize systems over willpower.

If motivation isn’t the answer, willpower must be what we need, right?

Not quite.

Here’s an example: When I was a student in the early portion of the Naval Special Warfare pipeline, I had to get up at 3 a.m. for workouts. Being late or missing a workout could mean being dropped from the program.

I made it to the workouts on time, but not by making myself promises or being super-duper disciplined every day. I simply put my alarm clock on the other side of my room.

I slept in a top bunk and had roommates, so when the alarm clock went off, I had to literally jump out of bed to shut it off.

I removed the possibility of failure from the path. It didn’t matter if I felt like getting out of bed. I had to.

Essentially, I created a system to help make getting out of bed feel like the obvious path forward—rather than an uphill slog.

Setting the alarm clock across the room was my system.

Systems help us prioritize what to do and when to do it. They also remove a lot of the effort and willpower we think are required to get things done.

This approach of shaping your environment to help yourself succeed works with any type of habit you’re struggling to stick to.

(To get started with creating your own routines to make difficult tasks easier, learn more about setting up health and fitness systems.)

#4: Separate your feelings from your identity.

In BUD/S, I was once in a support role keeping an eye on other students in the middle of Hell Week. The students were about three days into the week and were given a brief nap in tents on the beach. I was assigned to watch them for medical issues and get them to walk the 100 yards or so to the bathroom—rather than peeing in the same sand we’d be doing pushups in the next day.

One of those students stepped out of the tent and trudged past me toward the bathroom. His uniform was still wet with saltwater, and he shuffled along as if trying to shrink inward to avoid touching cold, wet cotton. He paused briefly in front of me, staring off into the distance, then burst into a full-body shudder.

With his eyes still affixed on the horizon, he said: “F**k I’m cold.”

With that, he resumed his slow, steady walk to the gate.

He was probably as miserably cold as he’d ever be in his life. He was hitting bottom, and he didn’t hide from it. He acknowledged what he was feeling, and set it aside. Being cold was a passing, unpleasant thing, like bad weather. It wasn’t his identity, and it didn’t shape who he was or what he chose to do.

Eventually, he graduated: A newly minted SEAL.

We often assume that our feelings should drive our behavior.

That if we feel tired or sad or discouraged, we should do tired, sad, and discouraged things. (Of course, expressing and acting on your feelings often does serve a purpose. It’s a release, and it sends a clear message to others.)

But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can recognize and accept those feelings in the same way that we grab a jacket when we see storm clouds passing over.

Our moment-to-moment feelings don’t have to determine who we are or what we choose to do. Simply knowing this can make it easier to carry on when we don’t feel like it.

#5: Use behavior to change negative feelings.

One way to deal with negative feelings—which will inevitably come up when pursuing a challenging goal—is to put behavior first. Over time, this allows us to have more control over how we feel in any situation.

In special operations selection, we used the phrase “quit tomorrow.” When we had particularly bad days, we would tell one another (or ourselves) that we’d just finish out the day. Tomorrow, we could be done with it all and never have to do burpees while soaked in saltwater and covered in sand again.

Inevitably, the next day would come. We’d realize the low point the day before wasn’t that bad, and we’d keep going.

In the long run, this took advantage of a phenomenon called self-herding.1 Self-herding is forming a new behavioral habit by subconsciously referring to what you did in the past under similar circumstances.

By not quitting in our low moments, we built a habit of finding a way to keep going whenever things got really bad. Over time, the urge to quit faded because we repeatedly reinforced that bad days still meant that we’d be okay.

Our choices don’t just reveal our preferences. They shape them.

If you’re applying this to your own habits, it’s the same process.

When you hit a low point, promise yourself you can quit tomorrow.

After this workout.

After this last round of meal prep.

After this section or chapter or lesson.

Over time, you’ll reinforce the decision and action to “do the thing that’s good for me right now,” and it’ll shape your future impulses and preferences.

#6: Use low moments to your advantage.

When we experience something that disturbs our equilibrium, such as a tough workout or a bad day at work, a subconscious part of our mind rapidly assesses two things:

- Do I know what’s happening?

- Do I have what it takes to cope with it?

Our perception of both are derived from experience.

The more things we throw ourselves into, whether we succeed or fail, the broader our experiences to refer to when assessing future stressors.

As years of varied experiences accumulate, we can begin to formulate a universal lesson:

No matter how many bad things you went through in the past, you were still alive when they were over.

This isn’t something you consciously decide. It’s something you teach a deeper part of your brain through practice.

The next time you crash and burn or feel like you keep getting knocked down, remember that even failure provides an opportunity.

It’s an earned experience that helps create a more accurate and effective stress appraisal in the future.

At some point, your mind will know that you’ve been there, done that—even when you’re in the middle of something awful. And you can calmly and rationally move forward with the benefit of hard-earned knowledge.

#7: View life as a series of learnable skills, and practice them.

Refer back to the power of the word “yet.” Resilient, effective people don’t just “try harder.” Rather, they see any process as a skill that can be developed.

Perhaps your self-talk turns toxic when you’re having a terrible day. Don’t just tell yourself to self-talk better. Identify the specific components of that process you can improve upon—and the contextual cues that will trigger you to do so.

Here’s how it might work:

- Identify a past experience when your self-talk became self-sabotage.

- Take that apart. What exactly was happening in your mind, and what were you doing?

- Decide on a specific practice that could be instituted in a similar situation in the future.

Perhaps when you were trying to get up for a 5 a.m. workout, you began mentally complaining and negotiating with yourself about getting out of bed.

Your future practice: Instead of complaining about how tired you are, you replace that dialogue with a different narrative. You tell yourself that you’re supposed to feel tired when you’re waking up. And that this early morning is the path you chose as a necessary step toward doing the thing that you truly want to do.

Or maybe you just replace the negative self-talk with a mantra or meaningful song lyric.

Whatever it is, be specific about what you’ll practice.

Then, in the same way that a runner times their splits on the track, time your ability to maintain this new practice. If you can replace or alter your negative self-talk for five minutes before breaking down, that’s your split. Reset your timer and start over next time.

The starting point doesn’t matter nearly as much as your willingness to improve, little by little.

Motivation, if anything, is an outcome.

You can’t control motivation. It can’t be directly pursued.

What you can control is the series of factors that underpin motivation.

Just knowing this can help you:

- stop waiting for a green light to get started

- realize that, even if it’s hard, taking action gets you closer to the goal that keeps you up at night

- understand that doing the right thing in the moment is totally within your control

With this approach, no matter what happens, you can move forward and make progress on any given day. And that progress, even if small, feels good and can be enough to keep you going… until the next day.

This is how you achieve great things.

Yes, it might be a long, slow, hard journey. But when we look back on our lives, what we remember most will be the things that were worth struggling for—and the way it felt to earn our happiness.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

You can help people build sustainable nutrition and lifestyle habits that will significantly improve their physical and mental health—while you make a great living doing what you love. We'll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification. (You can enroll now at a big discount.)

Share