We first envisioned an article about trauma a few years ago.

Over and over, we’d seen clients who checked out when they ate. Or shut down during workouts.

Or who raged when we made a relatively innocuous nutritional suggestion. (Like, “Consider eating slowly today.”)

Or who panicked. Disappeared. Became distressed. Got paralyzed.

Or seemed unable to cope with overwhelming urges to eat, restrict, purge, binge drink, or do a variety of other unhelpful behaviors.

As their coaches, we looked for individual explanations.

And we found them.

Painful childhoods with abusive or absent adults. Sexual assault. Emotional neglect. Substance abuse. Military service. Displacement. Miscarriages. Natural disasters. Grief and loss.

(If you want to see the authors discuss this article in even more detail, check out the video below. If not, simply scroll over the video player or click here to jump to the next section.)

PN coach roundtable: Robin Beier talks about how trauma affects health and fitness with Krista Scott-Dixon and Kate Solovieva.

But today more than ever, it’s apparent that trauma of all kinds can negatively affect client progress.

Racism, homophobia, poverty, sexism, ableism, transphobia, fatphobia.

Unsafe neighborhoods and communities. Lack of power and resources.

Violence, abuse, and bullying from the people who are supposed to protect them—partners, police, workplaces, health systems, schools, the government.

Economic uncertainty. A global pandemic.

No wonder many of us are having a hard time managing our eating, exercise, and self-care.

Yet remarkably: We still have the capacity to change and thrive.

To that end, this article aims to help—by providing insights and tools that you, as a nutrition, fitness, or health coach, can use to appropriately support clients who are struggling with trauma.

This article is about eating and exercise. But it’s also much bigger than that.

As humans, we’re called on to help make the world a better place. And to stand as advocates for all people harmed by suffering, injustice, and abuse.

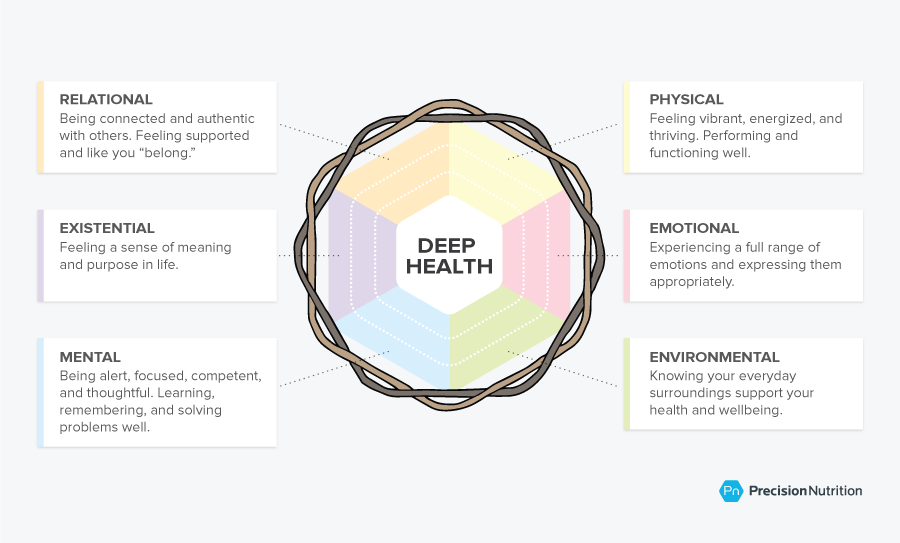

At Precision Nutrition, we support not just the “physical health” of our clients, but their deep health: nurturing all the things that make a complete human.

That’s because each domain of deep health—physical, emotional, mental, environmental, relational, and existential—affects all other domains.

And trauma? It can have negative and long-lasting effects on any of these domains, making it difficult for clients to experience meaningful progress in their health and fitness.

That’s where you come in.

As a nutrition, fitness, or health coach, it’s outside your scope of practice to ask clients directly about trauma.

But sometimes clients will tell you about traumatic experiences. Or they might do or say things that just don’t seem to add up.

Understanding how trauma manifests can help explain why clients often do puzzling or apparently unhelpful things, such as overeat when they’re also desperate to lose weight or be healthier.

Or neglect their own health and wellbeing even if they take great care of everyone else.

You should know how to respond and support these clients, because—unfortunately—trauma can happen to anyone, and it’s more common than many people realize.

Growth can happen for these clients, even in the face of overwhelming suffering. Humans are astonishingly resilient.

Being a trauma-aware coach can help you:

- understand people and their challenges, which will lead to more effective, productive coaching relationships

- understand why some clients behave “irrationally” or struggle with their eating and exercise habits

- identify strategies that can help clients get unstuck

- avoid re-traumatizing people, which is part of being a good person (and is probably smart for your business, too)

- recognize when a client needs additional support—such as a referral to a therapist—to work through trauma

++++

What is trauma?

Trauma is anything that overwhelms our existing resources and ability to cope.

How is trauma different from stress?

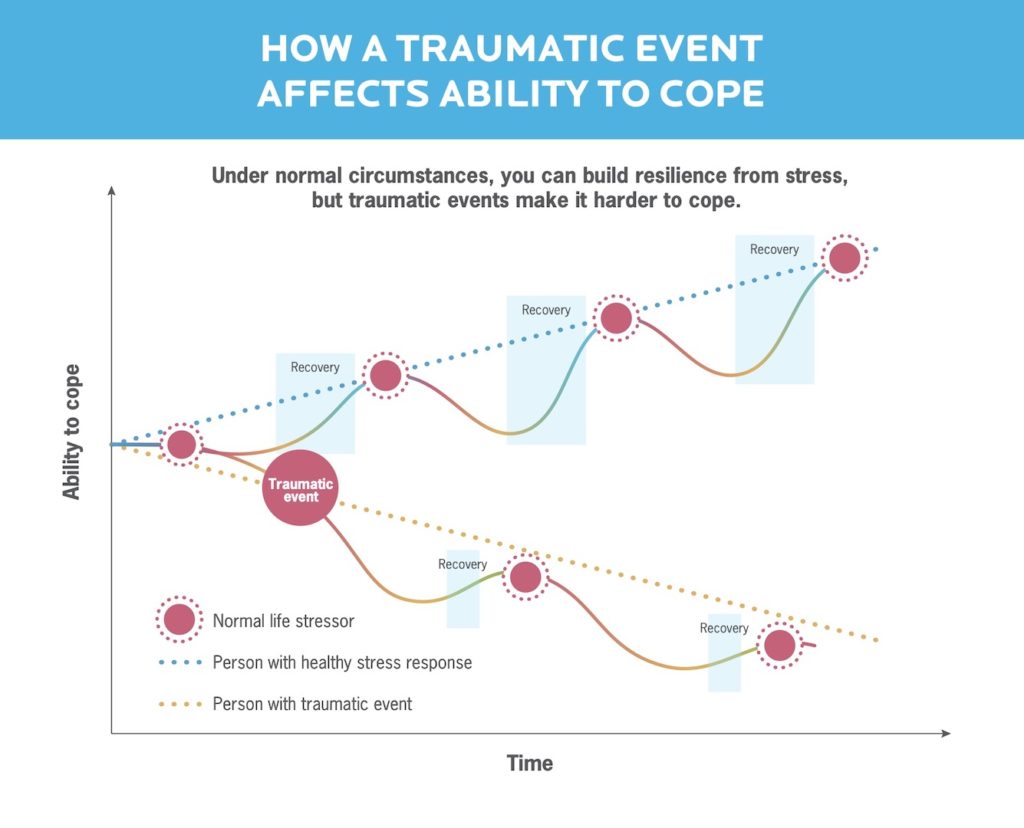

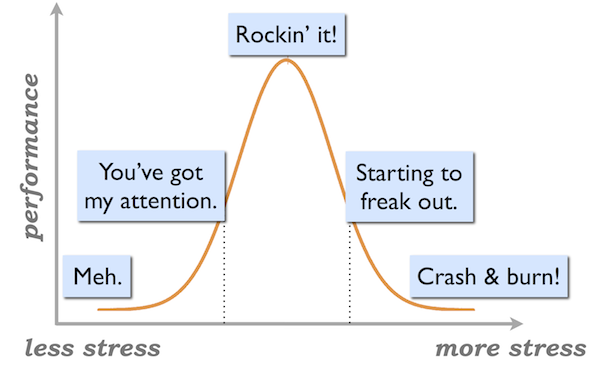

When we experience stress of any type, the body enters an alarm phase. In a normal situation, we eventually recover and get back to our baseline, or maybe even come away stronger and more resilient.

But with trauma, we experience the stressor so intensely that we’re unable to go through all the steps we need to recover. We end up worse off than where we started.

Trauma-inducing stressors can come from many different areas of our lives.

There are several types of trauma with varying degrees of severity, but they all can affect our health, wellbeing, and ability to care for ourselves.

Big-T trauma

Most people associate the word “trauma” with events like sexual assault, living or serving in a war zone, physical violence, or being in a car crash.

Because such experiences are extremely damaging and objectively terrible, psychologists refer to these as big-T trauma.

Usually, people know if they’ve experienced this type of trauma, although they may not be aware of its far-reaching effects.

Little-t trauma

Other times, traumatic events may seem like “no big deal” objectively, but they still leave a strong and lasting impression.

Little-t trauma refers to the more prevalent indignities, insecurities, injuries, and paper cuts of life.

- The experience may be something “minor” that hits in a vulnerable moment, like a parent who was largely absent during your teen years.

- Or it might be something deeply unfair or angering that happens over and over, like systemic racism or homophobia.

Little-t trauma can have lasting effects too. Many people experience it without ever recognizing it as “trauma.”

Collective trauma

We can also experience trauma as a group.

Collective trauma is a psychological effect that destabilizes the foundation of a society or group.1

Bombings, natural disasters, wars, famines, and pandemics are all obvious examples of events that can result in collective trauma.

Collective trauma can also come from violence, abuse, and indignities perpetrated against a specific group. This can happen cumulatively over time.

For example, the imposition of colonialism and residential schools on indigenous people in many countries such as Canada, the US, and Australia has had lasting generational effects.

People living through the collapse of a political regime, or in a general state of heightened awareness of violence—for instance, in a military state where they see guns on a daily basis—also suffer collective trauma.

(People may experience this type of trauma somewhat differently from individual trauma. Although it may feel less personal, trauma is trauma.)

Importantly, we don’t have to experience trauma directly in order to be affected.

For example:

- Parents may feel traumatized after a school shooting, even if their child doesn’t go to the school where the shooting happened.

- People who are alive in 2020 may have not experienced slavery directly, but the social scars of it are still “alive.”

This type of trauma can last for generations in our collective memories, and the meaning we find in these memories often goes on to shape society.

Intergenerational trauma

Trauma can be passed down through families in many ways.

First, if a person has experienced trauma, their behavior towards their child may change.

A parent or caregiver may repeat the traumatizing behavior they experienced, perpetuating the cycle.

Or, they may be so deep in their own coping mechanisms—such as abusing alcohol—they’re unable to provide for their child materially and/or emotionally.

Clients dealing with intergenerational trauma may tell you that their first issues with food appeared early in life when they felt scared, alone, small, angry, or otherwise distressed by what was happening in their families.

Second, the effects of trauma can be passed down via what’s known as transgenerational epigenetics.

Trauma can actually change how our DNA is packaged, and thus how our genes are expressed.

So traumatized people may give birth to babies who are epigenetically (i.e., biologically) predisposed towards mental or physical health challenges, increased inflammation, and/or more chronic disease.2,3,4,5,6,7,8

The most famous example is from research on the descendants of Holocaust survivors, which showed changes to genes in both parents and children.9,10 Other research has correlated a legacy of slavery with elevated stroke risk in African-American populations living in the southeastern United States.11

Similar effects have been observed in other marginalized populations (and in animal research), but this is considered an emerging area of science.12

Trauma isn’t “fact-based,” but perception-based and response-based.

A person’s subjective experience of an event or situation determines whether it was traumatic, regardless of how major or minor it seems.

Let’s say Fatima and Sonal both burned themselves on hot stoves when they were kids.

Neither of them remembers it that well, but they had similar experiences: Mom freaked out. They had to go to the hospital to treat the burn.

For Fatima, the experience wasn’t traumatic. She was upset and scared in the moment, but in the days that followed, she recovered. It didn’t leave any more of an imprint than skinning her knee on the playground.

For Sonal, the experience was traumatic. She already felt vulnerable because her dad wasn’t around, and her mom was always super stressed and working overtime to make ends meet. Though she hardly thinks about it now, the burn left a mental mark.

Now, as an adult, Sonal is wary of cooking. She doesn’t really know why.

She has stories to explain why she doesn’t cook. She’s busy. The stove just kind of seems… complicated. Or something.

But what made the experience traumatic was the context—not the burn itself.

Trauma is probably more prevalent than data indicates.

But here’s what we know: About 60 percent of men and 50 percent of women experience at least one significant trauma in their lives.13

Women are more likely to experience sexual assault and child abuse, while men are more likely to experience physical assault, combat, accidents, and disasters.14 Men are also more likely to witness death or injury.

Privilege and power are protective.

People from marginalized groups—such as people from racialized minority groups, immigrants and refugees, LGBTQI* people, people experiencing poverty, and so on—are much more likely to experience trauma.

But many people who’ve had big-T trauma don’t report it. And certainly most people who’ve suffered little-t trauma don’t.

What would they say?

- “I’d like to report my coworker being a racist or sexist a-hole?”

- “I’d like to report my mother being emotionally unavailable to me during a crucial point in my development?”

- “I’d like to report I only go out when it’s daylight so I won’t get harassed?”

- “I’d like to report a hot, corrosive rush of shame from something someone said, even though they weren’t even talking to or about me?”

For many folks, these types of events are just “how things are.” As famous feminist Gloria Steinem said about sexual harassment and assault in the 1960s and 70s, “We didn’t even have a word for it. We called it ‘life.’”

Many Precision Nutrition Coaching clients—and very likely many of yours, if you’re a coach—are dealing with the effects of trauma.

This can affect their eating and exercise behaviors, their self-care choices, and their ability to regulate their emotions.

Trauma affects how we eat, move, and live.

Although trauma manifests differently in different people, we tend to see common patterns.

Trauma changes our brains.

Often, trauma affects how a person behaves, defines themselves, and communicates with others.

Here’s what that might look like in interactions with clients:

They struggle to identify emotions, needs, and/or physical sensations. For instance, when you ask, “How do you know when you’re hungry?” or “Does that hurt?”, or “How are you feeling?”, they might say they’re not sure.15

They don’t seem to have the best memory. If you ask, “What was food like when you were little?”, or “What time did you eat dinner as a kid?”, they might not remember. They “forget things” like their daily coaching practices.

They often get stuck or paralyzed. The “freeze response” immobilizes us. Clients may say they feel unable to act, they avoid things, and/or they feel powerless. “I don’t know what happened, I just found myself eating… ”

Their story of themselves is deeply negative. “I hate myself. I’m a failure. I’m doomed. I can’t do anything right.” It’s hard for them to imagine that anything could be different or better.

They have a bigger reaction than expected. Seemingly mundane exchanges trigger fight/flight/freeze. Let’s say you suggest that your client try adding protein to their breakfast. They, in turn:

- Get super angry (fight)

- Walk away from the conversation (flight)

- Become very quiet or even completely disengage (freeze)

You might be shocked at what appears to be an over-reaction, but this is a deeply ingrained human response to fear and danger.

They always want to please you. This client might agree to literally every nutrition strategy you suggest. Eventually, it becomes clear they’re not implementing them. It just feels safer to go along with your ideas than to explain why it won’t work for them.

This is called fawning behavior. It’s often learned and employed by victims of abuse: By making themselves as invisible and agreeable as possible, they’re trying to protect themselves from further trauma.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A deeper look

Sometimes, traumatic events result in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD. We don’t know exactly why, but PTSD is most likely to occur in women16, military veterans17, and people who already have one or more traumas in their past.18

PTSD manifests in a couple of ways:

1. It can disorganize our sense of time, place, and space.

This affects how we remember a traumatic experience—often making it seem like the event is happening right now—and setting off a series of psychological and physiological responses such as dissociation, panic, and fight/flight/freeze.19

2. It affects how well we can reintegrate the traumatic event.

When something terrible happens, we may dis-integrate, or fall apart. To heal, we need to “re-integrate” the experience into our life and make meaning from it.

With PTSD, that reintegration never happens. Victims are left with persistent, long-standing cognitive, neurological, psycho-emotional disorganization, that we cannot, without treatment, resolve.

Trauma changes our physical health.

People with trauma may struggle with physical issues including:

● Hormonal problems, like an overactivated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a hormonal feedback loop that’s exquisitely sensitive to things like energy availability and stress.

When the HPA axis is hyperactivated, sex hormones, cortisol, and even brain neurotransmitters can get out of whack. The body may sound an alarm or simply shut the factory down.20

● Elevated inflammation, seen in biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and inflammatory cytokines, perhaps due to an overactivated HPA axis.21,22

This may be a reason childhood trauma is associated with a higher risk of health issues like heart disease, cancer, liver disease, and more.23

People with trauma may also have more chronic illnesses, particularly autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, chronic fatigue, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and allergies.24

● Unexplained pain, like long-standing, nagging pain or tightness that doesn’t seem to have a cause.

Maybe your client’s been X-rayed, MRI’d, CAT-scanned, and seen by every specialist. There’s no sign of injury. But the pain, restriction, and physical limitation persists.

Interestingly, the cumulative effect of stress, HPA axis/hormone dysfunction, and inflammation can actually increase pain perception.25,26 You know how things just hurt more when you’re stressed out? This is part of the reason why.

Stressed and hurting: The Bohr effect and pain

When we’re physically stressed—such as during an intense workout—we tend to inhale quickly and forcefully. Our exhales also get faster.

When we do this, it strips carbon dioxide (CO2) from the bloodstream.

This is an important bodily response. It helps the body dispose of the waste products generated by exercise, and enables us to deliver fresh oxygen to our muscles.

This dynamic relationship between blood CO2 and blood oxygen concentration is known as the Bohr effect.27

But if you’re sitting still and something stressful happens, you may experience the same shift in your breathing—deep inhales, short exhales. (Imagine a person hyperventilating during a panic attack.)

Except because you’re sitting still, there’s no increased oxygen demand in your muscles. If this happens frequently over time the following sequence of events can occur:

- You’ll have reduced CO2 in your bloodstream.

- Reduced CO2 in your blood ultimately reduces the amount of oxygen in your muscles.

- This alters the way you produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is what muscles use for energy.

- Changes to ATP production alter how muscles contract and relax, increasing baseline tension.

- Because your muscles can’t fully relax, you may experience chronic tightness.

This tightness is particularly common in postural muscles, such as the ones found in the lower back, neck, and shoulders. So in addition to increased pain perception, people dealing with trauma may also experience pain due to chronic muscle tightness.

The good news?

The tightness caused by dysfunctional breathing patterns can be alleviated, in part, by learning to breathe more efficiently.

In particular, practicing longer exhales can be very helpful in delivering more oxygen to the muscles, which helps them relax.

To learn more about breathing drills and why they work, jump down to helping clients learn self-regulation.

Trauma can change our nutrition, exercise, and health habits.

When people struggle with their behavior around food and fitness for years or decades, particularly with obesity or patterns of disordered eating, there’s a pretty good chance that something happened to them. And it doesn’t even have to be something “big.”

Clients with a trauma history may:

- Overeat and/or binge.28 Losing themselves in a binge can shut out the world for a while.

- Compensate after they feel they’ve overeaten. They may purge, or over-exercise, or fast.29 The endorphins released in a punishing workout, or from bingeing and purging, may provide a temporary high.

- Control and restrict their eating. In fact, they may alternate between this and losing control.30

- Come up with strict “rules” with harsh consequences. Like “I must work out two hours a day or else I’m a lazy walrus.”

- Do things that seem confusing or contradictory. Like going on a diet in the morning and binge eating in the evening. Or keeping trigger foods around to “test themselves,” even though they often “fail.”

- “Check out” or get “brain fog” around food. Like “I don’t know what happened, I sort of woke up and the bag of chips was empty.” Or, “I get paralyzed when I try to decide what to do. It’s just overwhelming.” Or, “I guess I’m just not motivated.”

The more intense the trauma in a person’s life, and/or the more frequent it’s been, the more likely they are to have physical symptoms and/or maladaptive behaviors, thoughts, and beliefs.

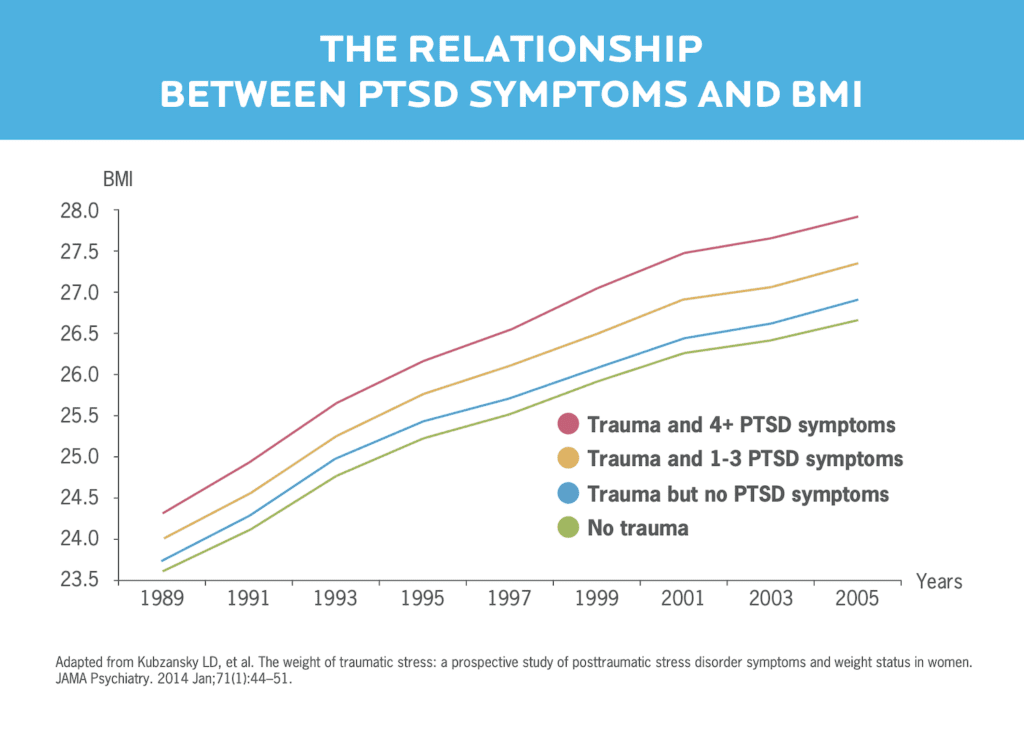

One study tracked the relationship of BMI over time, correlating it to trauma history. The graph tells an interesting story.

The more PTSD-type symptoms a person had, the more likely they were to gain weight over time.

Another study looked at the relationship between exercise tolerance and childhood abuse.

Researchers found that women who’d been abused were more likely to avoid exercise because the higher heart rate and feeling “amped up” evoked the same feelings of anxiety and fear they’d experienced earlier in their lives.32

Trauma can also change us for the better.

As human beings, we can feel about 50 different things at once and not have them be inconsistent. We’re complex.

We can feel horrible because of post-traumatic stress but still be growing.

A person might lose everything but then have that “screw it” moment where they reevaluate their life and decide to dump some crap and clutter overboard. That’s one type of post-traumatic growth.

Post-traumatic growth is when we change and evolve in good and healthy ways as a result of trauma.

It often involves finding meaning in our pain. For instance, we may vow to help others in similar situations.

It can help to think of post-traumatic growth like kintsugi, a type of Japanese pottery made from broken ceramics. Artists use precious metals to put the pieces back together, and the repaired version is considered more beautiful and desirable than the original item—especially because the process takes quite a bit of time.

If you know how to recognize trauma in your clients, you might just be able to help them take steps towards making repairs. They may find meaning in what they’ve been through. Or even discover the beauty in rebuilding.

7 ways to help your clients break the cycle.

#1: Familiarize yourself with the signs of trauma.

Good news: You’ve already accomplished this by reading this article!

Importantly, the reasoning behind understanding the signs of trauma isn’t so you can diagnose your clients. As noted earlier, that’d be a job for a qualified therapist. So unless you happen to be one of those, it’s important to stay within your scope of practice as a coach.

But knowing what trauma looks like helps you:

- support your clients and avoid retraumatizing them

- avoid feeling frustrated when client behavior doesn’t seem to make sense

- know when it’s time to refer out to a mental health practitioner

Educate yourself and be prepared to handle difficult material sensitively.

If you want to dig into some further reading, consider these resources:

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk, MD

- Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome by Joy DeGruy, PhD

- When The Body Says No and In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts, both by Gabor Mate, MD

- The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment by Babette Rothschild, MSW

#2: Affirm the validity of people’s feelings.

Don’t say “It’s no big deal.” It obviously is to them.

Don’t say “I understand completely.” You don’t.

Don’t say “Get over it.” They can’t, not without help.

Don’t avoid the topic and say nothing because it’s too icky or you don’t know what to say.

Instead, say: “I’m sorry for what you’re going through. Thank you for trusting me with this. I am here to listen and support you.”

#3: Maintain and respect boundaries.

Care about your clients but don’t become a caregiver for them. Know where you can help, and where you can’t.

Here at Precision Nutrition, we’ve come up with a code of ethics for coaches, as well as best practices for maintaining healthy boundaries with clients.

Familiarize yourself with these concepts. They’re important for all clients, but they can help establish a sense of safety with traumatized clients.

You should pay special attention to:

- Using open, non-confrontational body language to give off friendly, non-threatening vibes.

- Using a warm yet professional tone of voice.

- Establishing consent early and often if your coaching methods require physical touch.

That last point is key.

It may feel awkward to bring it up, which is why a lot of coaches skip it. Don’t be one of those people.

The guidelines here are simple:

- Any time you want to touch a client, ask: “Is it okay if I touch you here, like this?” Use hand gestures to indicate what you mean.

- Before you remove your hand(s) from a supportive position (such as helping to position their rib cage during a pushup), ask: “Is it okay if I remove my hands now?”

It might sound strange to ask about removing your hands, but doing so without asking can make a person with body-related trauma feel especially vulnerable.

Asking these questions gives a client ownership over what happens to their body. They can control who touches them, how, and when. And that’s how it should always be.

#4: If your client is open, explain the trauma response.

If you have a client who has disclosed trauma, it can help to share what happens during the trauma response with them.

Why? People are often really confused about what’s happening to them.

It’s a lightbulb moment to learn that what they’re experiencing is a physiological response to something that happened in their past.

It’s well worth taking the time to explain that their brain and body have learned a pattern of responding, and so what’s happening to them and their health struggles are not their fault.

When your client blanks out in front of the fridge, it’s not because they don’t have enough willpower or they bought the “wrong” groceries.

This realization can make a huge difference for the client and how they define themselves. They realize they’re not a bad person or lazy or that they can’t control themselves. They’re just repeating a pattern they learned long ago.

#5: Help clients learn to calm themselves.

This is a powerful skill that anyone can learn or teach. Here are three approaches to try.

Balloon breathing

“There’s a physical relationship between how you breathe and what your brain is telling your body to do,” says Craig Weller, CPT, PN Master Coach and resident exercise specialist. Exhaling triggers parasympathetic input from the brain, slightly slowing the heart rate.

By extending your exhale, you spend a little bit more time in the parasympathetic, calm-down state.

Try a longer, slower out-breath, like blowing up a balloon:

- Breathe out slowly for several seconds. You can count 1-2-3-4-5 if you like.

- Pause for a few seconds. Again, feel free to count.

- Then, consciously relax, and let the in-breath happen naturally.

- Repeat.

Core-engaged breathing

Putting your spine in different positions has differing effects on your nervous system via physical pressure receptors called ganglia.

Extending your spine (think upward dog in yoga) activates sympathetic receptors, turning on “fight or flight” mode.

Conversely, flexing your spine (think fetal position, or a puppy taking a nice nap), takes pressure off the spinal ganglia, producing a calming effect. Long exhales with your ribs and core in this position relieves the pressure even more.

Two versions of core-engaged breathing to consider: fetal position breathing and ribs-down breathing.

Grounding exercises.

These can help a client who struggles with “checking out” by drawing their attention to concrete physical sensations.

Examples of grounding exercises:

- Focus on the sensation of your feet on the floor

- Feeling the barbell in your hands

- Smell the rubber of the medicine ball you’re holding

#6: Have a referral network at the ready.

There may be times when you can’t (and shouldn’t) address all your clients’ needs on your own.

Keep some recommendations for mental health practitioners handy. These can be people you know in your community, or ones you’ve identified through research. If you’re not sure where to start, here are some ideas:

- If you live in the United States or Canada, check out Psychology Today’s Find A Therapist directory.

- In Europe, try the European Association for Body Psychotherapy or the European Association for Psychotherapy.

- In Australia, try Australia Counselling.

- Or Google your location with keywords like “trauma therapy.”

Make a list, and keep it handy. Try our referral worksheet.

Remember, referring out doesn’t mean you stop seeing your client. You can continue to support them in their health habits while they get specialized support in another area.

#7: Serve, but preserve.

There’s no getting around it. This is heavy stuff.

You may yourself have experienced trauma and be dealing with very similar issues as your client.

A lot of people choose to go to a coach over a therapist, for a variety of reasons—from not having health insurance to stigma around mental health.

While you should maintain your boundaries with clients and stay within your scope of practice, there are going to be times when you’re the only person a client can confide in.

But therapists have something coaches don’t always have in place: supervision and advisors. They regularly get together with other therapists to discuss cases, share advice, and get support.

As a coach, you can do something similar by talking with like-minded coaches regularly. Get that support.

Difficult subject matter can be draining. So make sure to charge your own battery.

Because your health is important, too.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a health and fitness pro…

When your clients are stressed and exhausted, everything else becomes a struggle: going to the gym, choosing healthy foods, and managing cravings.

But with the right tools, you can help your clients overcome obstacles like chronic stress and poor sleep—leading them toward the lasting health transformations they’ve always wanted.

PN’s Level 1 Sleep, Stress Management, and Recovery (SSR) Coaching Certification will give you these tools. And it’ll give you confidence and credibility as a specialized coach who can solve the biggest problems blocking any clients’ progress. (You can join the SSR Early Access List for our biggest discount + exclusive perks.)

Share