Chapter 6

Intermittent fasting schedules: Which one is best?

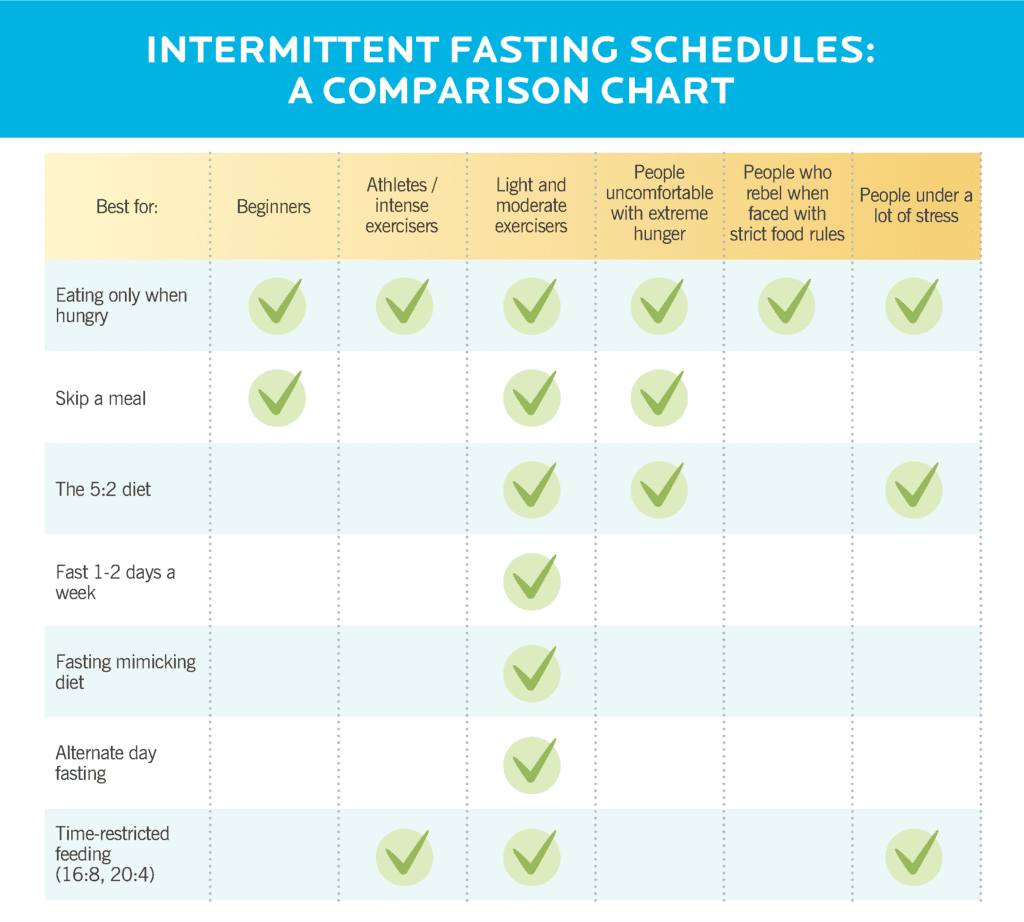

Whether it’s 16:8, 20:4, 5:2, alternate day fasting, or something else, determining the right intermittent fasting schedule for you (or a client) depends on a variety of factors. Here, we’ll outline all your schedule options, and provide you with specific advice for each.

Key concepts

- Is there a “best way” to fast that works the same for everyone? Probably not. (But that’s okay.)

- Match the plan to the person. People are different. So it’s all about finding the right path for each individual.

- There are many IF schedules. Feel free to explore them all, or pick one that seems like a good fit for your body, goals, and lifestyle.

- Look at the big picture. It’s easy to get lost in the details of specific schedules. Focus instead on the underlying ideas and practices that makes a fasting schedule work.

Intermittent fasting works—at least for some people. But which fasting schedule is best?

In this chapter, we’ll take an in-depth look at that question. But first, we must issue a warning.

No single intermittent fasting (IF) schedule will work for all people in all situations.

Sorry. We wish it were different.

It would make everything so much easier.

In reality, the effectiveness of any IF schedule depends on the person following it. We’ll explore that ultimate IF truth throughout this chapter.

In addition to reviewing the top IF schedules, we’ll help you figure out which one will likely work best for you or a client. We’ve included specific advice for:

- Skip-a-meal fasting, which is exactly what it sounds like

- Fasting for 12-24 hours as an experiment

- 16:8 fasting, or confining your eating to 8 hours of the day, and fasting for the other 16

- 20:4 fasting, or eating all of your food during a 4-hour window

- Fasting 1-2 full days a week, or not eating for 24 hours once or twice each week

- Alternate day fasting (ADF), or eating every other day

- 5:2 fasting, which is eating normally five days a week and restricting calories two days a week

- Fasting mimicking diets (FMD), or consuming half as much as usual for a few days to a week, then eating normally for 3-4 weeks

The best intermittent fasting schedules

Before you can choose the best fasting schedule for you, you need to know your options. Here, we’ve outlined the main ones, starting with the easiest and ending with the more advanced methods.

Schedule #1: Skipping a meal sometimes

Though it may not offer all of the physiological benefits of true IF, meal-skipping offers an easy way to ease into IF.

What it involves

There are a couple of ways to try this schedule.

Level 1: Wait until you’re hungry to eat. You might remember this from chapter 4 as “IF Lite.” So if you’re not hungry for breakfast when you wake up, for example, you might wait to have your first meal until 11am.

Level 2? Sometimes, don’t eat a meal you’d normally eat.

For instance, if you’d normally eat dinner, and you’re not actually hungry for it… don’t. Or skip lunch. Or breakfast. Try intentionally skipping a meal once or twice a week and see how you feel.

People who benefit

This is an approachable way for beginners to explore how their bodies and minds respond to hunger.

You’ll discover: Are you the type of person who can experience hunger, ride it out, and use what you learn to graduate to more intense fasting schedules? Or are you better suited to regular meals and snacks?

If you try it

-

- Consider the timing of your meals. If you plan to skip breakfast, for example, think about whether you want to eat lunch at your usual time or whether you’d benefit from having it an hour earlier?

- Plan how you’ll break your fast. If you have prepped food ready to go, you’ll be less likely to snarf down an entire pizza.

- Pay attention to your sensations of hunger. Do they come and go? Can you easily ignore them? Or do they continually distract you?

- Notice how you eat during your first meal after the fast. Do you consume your usual amount of food at the usual pace? Or do you gulp twice as much down quickly, and still feel unsatisfied?

Schedule #2: Fasting for 12-24 hours, as an experiment

Near the end of our year-long coaching program, we offer clients a fasting experiment:

Go a full 24 hours without eating.

(Or as long as possible, up to 24 hours, within the context of an average day.)

It’s scary, and it makes people uncomfortable. Which is exactly why we do it.

What it involves

There are no “rules” or protocols. For instance, people can wake up, have breakfast, then not eat again until breakfast the next day. Or they can have dinner on a Monday, then not eat again until dinner on Tuesday. Or whatever suits them.

The point is to simply try the experience of not eating for a while, and see what happens.

Afterwards, eat normally.

People who benefit

A one-day fast can be transformative for anyone who associates the sensation of hunger with “emergency.” That tends to include people who learned from their parents that they should eat three square meals a day, as well as finish everything on their plate.

It’s also great for people who fear being deprived or restricted, assuming that once they start getting hungry, it’s going to get worse, and worse, and worse (which, by the way, isn’t true).

And finally, it’s a great first step that allows you to test the waters, seeing if a more extreme fasting schedule—such once- or twice-weekly fasting—might work for them.

If you try it

- Notice your physical sensations, and how they change. Pay attention to the physical feeling of “empty” versus the more familiar feeling of “full.” Or how hunger comes and goes. Or how your energy level shifts. Or fluctuations in your ability to concentrate. Or whatever else your body shows you. Try to look at these feelings with curiosity.

- Notice changes in appetite afterwards. You might notice that you’re hungrier than usual immediately after a day of fasting, or during the next few days. This can easily lead to overeating, so it’s something to be aware of if you’re considering fasting on a more consistent basis.

- Notice bargaining and storytelling. It’s easy to play little games like “rewarding” yourself for having a fasting day. Again, this can lead to overeating.

- Notice whether this experiment pushes you to go further, and consider whether that’s healthy and appropriate for you. If you learned a lot about hunger, didn’t hate the experience, and ate normally the day after the fast, then fasting one or two days a week (see schedule #5) might be for you. On the other hand, if you spent the day staring at the clock and the following day with your face buried in an apple pie, full-day fasting may not be your jam.

Schedule #3: 16:8, 20:4, OMAD, and other types of time restricted feeding

Popularized and researched by Satchidananda Panda, PhD, time-restricted feeding (TRF) combines a fasting window with a feeding window. During the fasting window, people either don’t eat at all or eat much less than usual. During the feeding window, people may either eat normally or more than normal.

In theory, this protocol takes advantage of our natural circadian rhythm to optimize metabolic health.

What it involves

Three of the more popular types of time-restricted eating include:

- 16:8, which calls for a 16-hour fast followed by an 8-hour eating window.

- 20:4, which entails fasting for the first 20 hours of each day, and then eating only during a 4-hour “overfeeding” window. Generally, most people put their 4-hour overfeeding window at the end of the day, as it’s more convenient for family dinners and after-work training sessions.

- OMAD, or one meal a day, which involves consuming all of your calories within 1 hour and nothing for the other 23 hours.

In each approach, some people focus on including highly-satiating foods such as colorful veggies and lean protein. These foods can help to dampen hunger during the fasting window.

For someone following 16:8, it might look like this:

Monday, 8pm: Finish your last meal of the day.

Tuesday, 11am: Work out.

Tuesday, 12pm: Eat your first meal, ideally the biggest one of the day.

Tuesday, 12-8pm: “Feeding window” during which you eat your daily energy intake.

Tuesday, 8pm: Last meal of the day ends, and the fasting period starts.

People who benefit

Time-restricted eating is a great next step for anyone who skips a meal (see schedule #1) and thinks, “I could eat like that every day.”

It can also work nicely when your lifestyle or personal preferences just plain interfere with things like eating breakfast every day. For someone who never enjoyed breakfast, it can be a relief to wait until 11am or later to start eating. And for people who work at night, a big meal at 3 or 4pm—and nothing afterwards—might help them stay focused at work.

If you try it

- Start with a trial period. Pick an eating window you’re confident you can handle, such as 12 hours. If all goes well, you can shrink the eating window from there. So if you normally eat dinner at 7pm, you might shift to a 6pm meal instead. The next day, try 5pm. And so on.

- Be flexible about the eating window. Many people find that, with some experimentation, they land on a fasting/feeding schedule that falls outside of the 16:8 and 20:4 methods. For example, they might eat strictly 16:8 during the week, but graze all weekend long. Or they might alternate between 16:8 and 20:4 depending on what’s going on in their lives.

- This is about more than just timing. No fasting schedule will make up for a poor-quality diet. Nutrition fundamentals still matter. Eat real food, and eat it slowly. (For more about the fundamentals, see “The 5 universal principles of good nutrition.”)

- Experiment with training on an empty stomach. See what happens when you get your workout in before you have your first meal. (Note: Caffeine helps many people work out while fasted). Then have your biggest meal right after your workout.

Here’s what happened when I tried time restricted feeding.

Krista Scott-Dixon, PhD, Precision Nutrition’s director of curriculum, is a morning person.

“I didn’t want to give up my big breakfasts, so I chose evening fasting first.” she says. “I normally trained in the mornings, so this worked for me.”

However, she noticed three things about her sleep when fasting in the afternoons and evenings.

First, she was much more tired. “Once my battery ran out, I was done. Getting up the stairs to bed was a terrific ordeal,” she says.Second, although she’d conk out quickly, she didn’t sleep well.

Third, she woke up extremely early—at a consistent 4am.

Later, she experimented with skipping breakfast and lunch.

“At first, that felt like much more of a sacrifice,” she says,

Eventually she got to like the efficiency of waking, grabbing a cup of tea, and getting straight to work. And she slept a lot better after a good meal in the evenings.

Bottom line: For any fasting schedule, you’ll want to experiment, tweak the plan, and do what works for you.

Schedule #4: The 5:2 diet

Popularized by Dr. Michael Mosley’s The Fast Diet, this approach involves consuming a lot less food two days of the week, and eating normally the other five.

Maybe you’re thinking, “That’s not fasting! That’s part-time dieting!” And you’re right.

Technically, this style of eating is called intermittent energy restriction (or IER).

What it involves

Exactly what and how much someone eats on the two “fasting” days can vary from around 20 percent of normal intake to 70 percent. For someone consuming 2800 Calories a day, a fasting day might range from 560 Calories to 1900.

As you can imagine, the lower end of that range is a lot more challenging than the upper end.

People who benefit

People who do best with 5:2 fasting tend to have a lifestyle and/or fitness schedules that align with it.

Here’s an example: Robin Beier, PN2, is a German nutrition coach who practices IF personally and coaches a number of clients who do the same. In Germany, most shops are closed on Sundays, including grocery stores. So for one of his clients, a 5:2 diet naturally emerged.

This client would wake on Sunday with hardly any food at home—and didn’t want to eat out. So he’d have breakfast and then eat either very little or nothing at all for the rest of the day. He broke the fast Monday evening, after hitting the grocery store for dinner supplies.

If you try it:

- Experiment with fasting-day meals. Many people find that small meals composed mostly protein and colorful veggies work best, as they help to dampen hunger.

- On non-fasting days, don’t forget the nutrition fundamentals. Eat slowly and mindfully. Choose minimally-processed, whole foods most of the time. And consume a variety of colorful veggies, lean proteins, and healthy fats.

- Play around with adding more fasting days—or subtracting them. For example, someone might do a 6:1 diet: dramatically reducing their intake one day a week, but eating normally for six. Another person might do a 4:3—fasting three days out of every four.

Schedule #5: Fasting 1-2 days a week

On this plan, you fast for a full 24 hours once or twice per week, eating sensibly (higher protein, minimizing processed foods) the other days of the week.

What it involves

It’s flexible: You can choose whichever 24 hours you want.

People who benefit

This is an advanced fasting schedule.

It works best for people who’ve tried either meal skipping (schedule #1) or a one-day fasting experiment (schedule #3) and thought, “Gee, that was interesting. Let’s see what happens if I push this a bit more.”

Note that if you’re not ready to fast one or two days a week, there’s a nice half step. You can just fast for 24 hours occasionally—say, once a month—as a refresher to remind yourself that hunger is no big deal.

If you try it

- Start with just one fasting day. Two fasting days can be stressful (see the box below for more info).

- Take an honest look at the rest of your life. Fasting doesn’t pair well with things like the sleep deprivation that comes from being a new parent or exhaustion from training for a marathon.

- Train on your non-fasting days. This is especially important if you’re exercising intensely.

- On your non-fasting days, eat real food. We’re talking plenty of lean protein, colorful veggies, healthy fats, and minimally processed carbs.

- On your fasting days, practice radical self care. Relax. Drink plenty of water or tea. Wrap yourself in a cozy blanket. Breathe deeply and find comfort in ways that work for you.

- Plan for how you will break your fast. Have food you feel good about eating ready to go. Take a few breaths before your first bite. Slow down and enjoy.

We fasted 2 days a week. Here’s what happened.

Fasting just one day a week worked great for Precision Nutrition’s co-founder, John Berardi, PhD. Sure, on that first day without food? Hunger dogged him. His family also reported that he was quite crabby.

But he adapted. And with an “eat anything” day once a week to counteract his “eat nothing” day, everything felt doable. After roughly five weeks of fasting, “I was barely uncomfortable at all,” says Dr. Berardi. “And by my seventh or eighth fast, I was having great days.”

Dr. Berardi lost 12 pounds of body weight during the first eight weeks on this schedule.

Dr. Scott-Dixon? She had similar experiences.

But when they both tried to add a second fasting day? Everything went sideways.

Within two weeks, Dr. Berardi’s morning weight plummeted from 178 pounds to 171, with an estimated 4 additional pounds of fat lost… but he lost 3 pounds of lean mass, too.

He felt small and weak, and was losing too much weight too fast.

People commented on how “drawn and depleted” Dr. Berardi looked. And he was exhausted. Training became a struggle. Even getting off the couch was a struggle.

Dr. Scott-Dixon had a similar experience.

“In particular, people commented on how awful my face looked,” she says. “Family members worried that I had a terminal disease.”

To try to turn the miserable experience around, Dr. Berardi added a second “eat anything” day that included up to 5000 Calories of, well, whatever he wanted. It helped some, but he was still preoccupied with food and ultimately decided that twice-weekly fasting just wasn’t worth it.

The lesson: When it comes to fasting, do just barely enough to meet your goals.

And maybe even a little bit less than you think you “need.”

Schedule #6: Fasting mimicking diets

Fasting-mimicking diets (FMD) are similar to the 5:2 diet, except the time scale is longer:

- The low-energy period usually lasts around 3-7 days.

- It’s done less often, generally once every 3-6 weeks.

What it involves

In practice, an FMD might include 1 week of low energy intake, say around 50 percent of normal needs, then 3-4 weeks of normal energy intake. Repeat.

People who benefit

This is an advanced fasting schedule that works best for people who have already mastered 5:2 eating or another less intense protocol.

It’s ideal for people whose lifestyles reinforce the fasting schedule. Consider the life of a long-distance trucker who spends a week on the road followed by a couple weeks at home. Such a person might decide to eat very little while driving.

Why? For one, they’re quite sedentary, so their body doesn’t need as much energy. Two, they may be incentivized to drive as long as possible and not want to take lots of breaks.

Then when that trucker arrives home, they might eat more normally.

If you try it

- Take extra care of yourself during your fasting week. Many people can ride out hunger for a day or two. But a week? That takes practice. And commitment. As much as possible, pair your low energy period with activities that fill your cup.

- Practice eating less. Before trying an FMD, experiment with milder fasting schedules. Try eating less for a day. Then try two days. Then three, and so on.

- Be flexible. Plan for what you’ll do if you mess up. Because you will mess up. If you planned to do a seven-day low energy period but only get through four, that’s okay. It really is. Rather than beating yourself up, consider what you can learn from the experience.

- Don’t forget to drink fluids. This is especially important if you usually only consume fluids with meals.

- Enlist some help. You’ll need to carefully plan your food intake to make sure you’re meeting your micronutrient needs (vitamins, minerals, and so forth), so it helps if you’re working with a nutrition coach or another qualified practitioner.

Schedule #7: Alternate day fasting

With alternate day fasting (ADF) you eat every other day.

What it involves

You eat normally one day. The next day, you don’t eat. Repeat.

People who benefit

This is an advanced fasting schedule that works best for people who have already mastered fasting one or two days a week.

As with schedule #6, it’s ideal for people whose lifestyles reinforce the fasting schedule. Think of hospital medical professionals who work 12-24 hour shifts. For them, it might be easier and even preferable to not eat during their shift.

If you try it:

- Practice fasting for shorter periods, first. Again, this is an advanced practice. Before trying alternate day fasting, experiment with fasting once or twice a week.

- Plan for when you will break your fast. Make sure you’ve got food at the ready.

- Be flexible. If you break the fast early, you didn’t screw up. Try to learn from it and move on. Also, try not to compensate for mistakes by fasting even harder. For example, if you eat dinner on a fasting day, don’t skip a meal on your eating day in order to make up for it.

- Take time off from fasting when your life gets busy. ADF doesn’t pair well with hard training, excessive life stress, or even someone’s monthly menstrual cycle.

Watch out for the side effects of intermittent fasting

Your sex, stress level, and age can increase the chances of IF side effects like insomnia, fatigue, and poor recovery. This is especially true for intense fasting schedules like alternate day fasting.

Side effect #1: Intense fasting can disrupt sex hormones.

If estrogen is your dominant sex hormone (for instance, those assigned female at birth), you may be more sensitive to energy intake than someone who has testosterone as their dominant sex hormone (for instance, those assigned male at birth). Piling on too many stressors—extreme exercise coupled with extreme dieting, for example—can lead to a cascade of problems, including:

- mood disorders and mental health problems

- thinking and memory problems

- low bone density

- joint injuries and inflammation

- digestive problems

- poor recovery and repair

- sleep problems

- cardiovascular and other metabolic diseases

(Read more: Intermittent fasting for women.)

In Dr. Scott-Dixon’s case, too-frequent fasting combined with too-heavy training as well as general life stress and an anxious temperament resulted in estrogen, progesterone, DHEA, LH, FSH, and cortisol levels that were effectively zero. “I was in my mid-30s and menopausal,” she says. “I’ve seen this situation in many of my female clients—some as young as their mid-20s.”

As a result, most women will want to gravitate toward the gentler forms of IF and be careful about how they pair those options with a fitness program.

Side effect #2: IF is a stressor, which can make you feel run down.

If someone’s under a lot of pressure, a gentler form of fasting is probably best. If you attempt an advanced fasting schedule such as ADF, you’ll want to give your body plenty of TLC on your fasting days—and schedule exercise for your eating days.

Side effect #3: The older you are, the less fasting your body will embrace.

If you’re older, your “reserve tank” of hormonal production is already relatively lower. So if you add fasting, especially if you’re also already lean, you’re going to deplete that tank even faster. Tread carefully.

For coaches: Find the best intermittent fasting schedule for your clients

The topic of IF poses quite a few challenges for nutrition coaches. First, some clients really shouldn’t be fasting at all. (For a refresher, see chapter 4.) Others might do okay with some fasting approaches, but miserably on others.

And still other clients might come to you convinced that the most extreme fasting method is right for them, even though they’ve never fasted before.

How do you navigate these turbulent waters? In this section, you’ll find advice from Robin Beier, PN2, a German nutrition coach we mentioned earlier in this chapter.

To match clients with an intermittent fasting schedule, consider these questions.

Factor #1: Have they practiced the fundamentals?

A number of fundamental nutrition strategies form the underpinning of all successful IF schedules. Your client will want to have these down before trying any fasting style. Is your client usually…

- eating only when physically hungry?

- eating slowly until satisfied?

- consuming minimally-processed whole foods?

- eating balanced meals that include lean protein, healthy fats, smart carbs and colorful veggies?

If possible, try to spend some time on these practices before diving into any of the fasting schedules mentioned in this chapter.

Factor #2: Have they fasted before? If so, how did it go?

Consider asking: “What experiences have you had with fasting schedules or meal skipping?”

Your client might tell you, “Yeah, I sometimes skip breakfast, especially when I run out of breakfast cereal.” That’s a golden opportunity to follow up with another question: “How did dinner go?”

If your client shrugs their shoulders and says, “Like usual,” they might be able to handle more advanced fasting, though you’ll want to work them up to it. On the other hand, if your client says, “Oh, dinner was horrible. I stuffed my face!” you’ll want to start with only the gentlest approaches.

Factor #3: What kind of exercise are they doing? And how often are they doing it?

Clients who train intensely will want to choose milder fasting schedules, such as skipping a meal, 16:8 time restricted eating, or fasting once (but not twice) a week.

Factor #4: What’s their lifestyle like?

You want a schedule that complements someone’s life rather than complicates it.

For example, busy medical professionals who work long shifts might find that 20:4 or ADF helps them stay productive at work, whereas someone with a desk job might complain that the very same schedules interfere with their ability to get things done.

To get a sense for how a schedule might fit someone’s life as well as their personal preferences, you might ask questions like:

- “What’s easier for you: To eat a little bit less in the morning? Or to eat a little bit less in the evening?”

- “What’s easier for you: To eat a lot less than usual for a day or two each week? Or to eat nothing for a full day?”

- “What’s easier for you: To eat during certain hours of the day? To skip meals? Or to fast for a full day?

Factor #5: How do they feel about specific fasting schedules?

Ask your client, “On a 1 to 10 scale, how confident do you feel about your ability to follow this plan?” If your client tells you a 9 or higher, you’re in great shape. But if their answer is 8 or lower, you’ll want to take steps to shrink the change. Here’s how that might look for various fasting schedules:

- Instead of meal skipping: Eat lightly (say, two apples or a small salad) or delay the meal by an hour.

- Instead of 16:8: Start with a 12:12 schedule and expand from there.

- Instead of full-day fasting: Fast for breakfast, eat a light lunch and have a normal dinner. Alternatively: Eat a late breakfast, and fast for lunch and dinner.

Two words that can reign in overzealous clients

What do you do if your client wants to go full steam ahead with a fasting schedule that, most likely, is too much for them?

In those cases, coach Robin likes to say two words: “Show me.”

For example, “You want to do two weekly fasting days? Cool! Show me you can fast for one first, okay? I want to make sure we don’t run into any problems and we can always make it harder.”

And know that, in some cases, no matter how eloquently you steer the conversation, your client may push back, saying, “Well, I think alternate day fasting is exactly what I need, so that’s what I’m going to do.”

Because that happens sometimes.

In that case, suggest trying it as an experiment.

Don’t fret about the details here. Just help your client get a handle on the underlying ideas behind whatever schedule they want to try. And then help them learn from the experience. Chapter 8 will show you how.

But before we get to that… In the next chapter we’ll look at how IF can impact workouts, and how to optimize your performance while fasting.