For more than 40 years, people in the West have been running on built-up “squishy” shoes, hoping to prevent injury and go faster. Yet “barefoot” runners argue that running without shoes or in minimal footwear is safer and better.

Who’s right? And what kind of shoes should you wear for the healthiest running experience? Find out in this thought-provoking article.

[Note: we’ve also prepared an audio recording of this article for you to listen to. So, if you’d rather listen to the piece, click here.]

++

A brief history of squishy shoes

Once upon a time, people ran without shoes. Or else they wore simple sandals, like huaraches. They pounded along packed-dirt pathways. They charged through rocky canyons. They galloped across green grasslands. All barefoot, or nearly so.

In some parts of the world, people still run like this.

Meanwhile, during the last four decades in the West, an entire industry has grown up around running shoe technology.

These days, a lot of us believe that unless we’ve strapped on our gel-arch-pronated-supinated-midsoled-outsoled-lace-patterned-mega-industry runners, we shouldn’t even think about hitting the streets.

But there’s also another camp: The so-called “barefoot” runners.

They say the craze for built-up shoes is little more than baloney. They believe we’d be better off returning to a more “natural” shoe for running. Or even leaving off our shoes altogether.

So who’s right?

Jogging along

People have been running since the dawn of time. To hunt, to escape danger, and even for the simple joy of it. In fact, records of competitive running date back as far as 1829 BCE.

But it wasn’t until the 1960s that non-conditioned athletes began to take up regular running as a form of exercise. And with this new group of recreational runners came a whole new interest in sport-specific footwear.

Soon the iconic Nike waffle tread hit the stores. Its success may have been due to the fact that it was lighter than most shoes then in use.

Compared to its successors, the amount of heel lift in this shoe was next to nothing.

Just for comparison, take a look at the original shoe compared to the “tribute” version in 2007.

See the massive amounts of foam and the elevated heel? Quite a difference.

So what happened during that thirty-year period to change the shape of shoes? New materials, and “science”.

From the mid 1970s onwards, running companies got scientists involved in footwear design. This is when the terms “neutral”, “pronation” and “supination” entered runners’ vocabulary.

Suddenly, it wasn’t enough simply to buy the shoe that seemed to fit best and feel most comfortable. Instead, you had to figure out your running “style” and pick a shoe to “correct” your running dysfunction and prevent injury.

It sounded sensible, in theory. After all, who wants to get hurt?

There was just one little problem. Despite the involvement of scientists in the design, no style-specific running shoe has ever been shown to reduce injury!

Shoe business

Meanwhile, back in the factories, inventors were slapping together new types of rubbers. Slotted into the soles of shoes in order to improve lift, reduce shock, and “re-energize” the foot over lengthy runs, these new materials were supposed to help you “go the distance” in greater safety.

Yet recent investigations suggest that these fancy soles don’t actually stop us from getting a shock when our feet make contact with the pavement. Instead, they stop us from noticing it.

Insights like this have led the trend toward more minimalist shoes.

In 1999, designer Robert Fliri took out a patent for a “five-finger” shoe, first manufactured by Vibram in 2005.

In the years since, five-finger and other low profile shoes have surged in popularity. From public forums to sports magazines, more and more athletes and ordinary people tout their benefits.

If the shoe fits…

These days, we can run unshod (without shoes); minimally shod (in shoes with no heel lift and little cushioning); or shod (in cushy and inflexible sneakers with heel lift.)

It’s great to have options. But sometimes they make life confusing.

So before you buy your next pair of shoes (or throw your shoes away) you probably want to know:

1. Is one approach better for performance?

2. Is one approach safer?

And you probably want to use evidence to make your decision.

What the research says

If you want the Cliffs Notes/Coles Notes version, the jury’s still out.

There simply aren’t enough studies to support any absolute claims.

What we do know is that running barefoot or in minimalist shoes may improve performance. But this might relate more to stride than to the shoe itself.

Meanwhile, we don’t yet know for sure whether minimalist shoes reduce the risk of injury compared to more built-up shoes.

Does that mean that squishy shoes do prevent injury?

Not quite.

Form, not footwear

Here’s a curious fact. Despite shoe manufacturers’ claims that built-up sneakers will protect us, they haven’t reduced the rate of running injuries: In the past four decades, running injuries haven’t happened any less often.

In fact, none of the research looking at various kinds of shoes shows any real effect on injury.

It turns out that our running gait actually matters more than the shoe.

And good form — which includes impact forces and compliance — can protect us from injury and improve our performance far more reliably than any type of shoe.

Impact forces

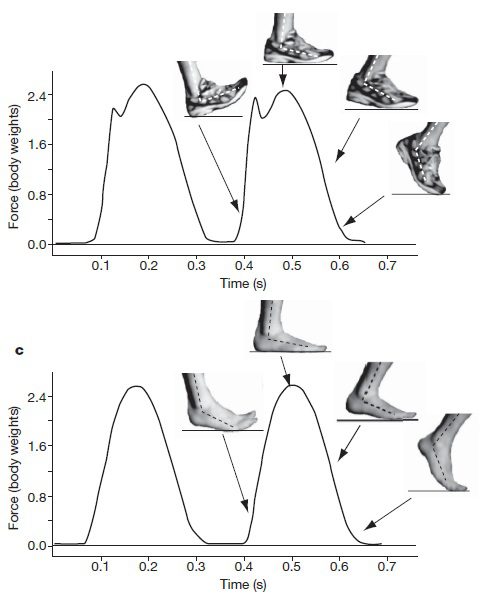

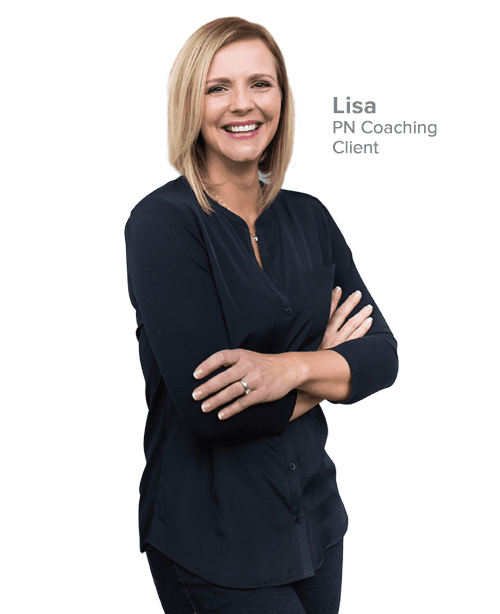

Basically, there are three kinds of runners.

- Rearfoot strikers (their heel hits the ground first)

- Midfoot strikers (the ball of the foot, then the heel strikes the ground)

- Forefoot strikers (the ball of the foot hits the ground and the heel never really touches down).

Most of us have a preferred or instinctive style. But we can learn to use a different gait. And our footwear (or lack of it) may affect our gait.

Research demonstrates that people who run barefoot tend to strike in the forefoot or midfoot first.

Meanwhile, shod runners tend to strike the rear of the foot.

In fact, padded inflexible shoes may actually convert some people to this gait. Especially those who are instinctive midfoot strikers.

How so? Well, the built up part of the shoe is so big that mid foot landing becomes virtually impossible. Rearfoot striking becomes the path of least resistance.

Rear, middle, front—what’s the difference?

Rearfoot strikers land with significantly greater force than midfoot strikers or forefoot strikers — a force equaling 1.5 to 3 times their body weight.

Just imagine how you’d feel if an object 1.5 to 3 times your weight repeatedly crashed into another part of your body.

Ouch! No wonder running can take a toll.

Meanwhile, the impact appears much smaller for midfoot strikers and forefoot strikers.

Compliance: Increasing movement response

Not only do rearfoot strikers hit the ground harder, they also run with a fairly stiff, extended leg. This position sends a lot of additional force up the body.

Forefoot strikers and midfoot strikers are at an advantage here again. With knees bent and their feet positioned more under their hips, their ankles are correspondingly softer and more “compliant.”

That means they are more responsive to the environment. Forces in a run can be adjusted in real time.

Want to know what I mean? Try running barefoot in the grass or sand, and see how your gait delicately and quickly responds to the terrain.

Common injuries

Oh, dem bones

Based on the above, it’s pretty easy to see why impact (or micro) fractures are one of the most common running injuries around.

No wonder manufacturers have added cushioning to their shoes.

This cushioning may cut down the impact of rearfoot striking a little bit.

But only by about 10% at most. Much of the force remains. We just don’t feel it the same way. Which may be worse for us in the long run. (So to speak).

With all the force that running generates, you’d think it might help us build stronger bones.

Alas, running has many great benefits, but building bone mineral density is not one of them.

To build bone mass, we need muscle mass. And the biggest known contributors to bone mineral density are stop-start sports like racquetball and soccer, and resistance training for loading bones along their lengths.

The connective tissues

Apart from microfractures, another common runners’ complaint is plantar fasciitis, sometimes called “jogger’s heel”.

Though most of the pain is felt in the foot, it’s actually caused by tight calf muscles or Achilles tendons.

Rear foot striking can increase the likelihood of developing plantar fasciitis. Midfoot and forefoot strikers don’t seem to face the same risk.

The environment

This may seem obvious, but it’s easier and safer to run barefoot or minimally shod in some places than others.

Contrary to what you might think, hard ground may not pose any particular risk — assuming a forefoot or midfoot striking gait. But weather conditions and other factors might.

It’s not a great idea to run truly barefoot in snow and ice. Shoes do help buffer us a bit against frostbite.

Dr. Mick Wilkinson may compete barefoot in the Great North Run in the UK, but runners in Iqaluit should think twice. If your feet are numb, by definition, you’ve lost sensation. And if you lose sensation, you can injure yourself without being aware that it’s happening. Bad news.

Plus, if you live in a neighborhood littered with broken glass, sharp pebbles, needles, or rusty nails, you probably want some protection on your feet.

Running barefoot at night is also extra risky, for obvious reasons. If you can’t see the ground, you might step on something you don’t want to.

In short, it’s one thing to run barefoot on a sunlit beach in Aruba. It’s another thing to try it on a January night in the Bronx.

Bottom line

Running barefoot or minimally shod tends to promote a forefoot or midfoot striking gait. But does this mean that barefoot or minimally shod runners get fewer injuries?

Maybe, but we don’t have enough research to say for sure.

What we do know is that cushioned, inflexible shoes may contribute to a false sense of security about gait. We become less aware of how we’re running.

That’s a problem because shoes don’t eliminate impact forces associated with many running problems. However, gait awareness and, if necessary, gait modification can.

Meanwhile, be careful if you do decide to transition to minimal shoes or to running barefoot after using built-up shoes. Feet and legs need time to get used to the new positioning. Build up slowly, and be realistic.

What about performance?

Barefoot and minimally shod runners tend to take shorter, faster strides than shod runners, regardless of speed. And this is generally a good thing.

There are some interesting tradeoffs between stride length and frequency, but in distance running, elite athletes have a turnover of around 180+ steps per minute, where non-elite runners tend to have turnover rates of about 140-160 steps per minute. Shod runners also tend to run at 140-160 steps per minute, regardless of speed.

This simple statistic suggests that minimalist footwear, which puts the foot more under the hip, helps to promote an elite level cadence and reduces over-striding.

On the other hand, research also shows that rearfoot strikers consume a bit less oxygen than midfoot strikers when running at under 15 km/hr. Theoretically, this could translate to better performance.

Yet midfoot strikers still perform extremely well at energy-taxing ultra-marathon events, to take just one example.

In other words, it looks as if no one variable tells the whole story about performance.

Other reasons to consider minimalist footwear

By now, you’ve probably figured out that minimalist shoes or barefoot running promote a healthy running stride. However, it’s possible to run this way in high tech shoes as well.

Indeed, ChiRunning — a program designed to improve running technique — was encouraging forefoot striking and other related mechanics as far back as 1999, before the rise of minimalist footwear; sport scientist Michael Yessis did the same in his 2000 book Explosive Running.

Yet there might be other compelling reasons to switch.

Experienced minimalist runners say they have a better awareness of their bodies in space (aka proprioception). Greater proprioception in turn improves balance and stability.

Also, with greater feedback from the terrain, joints get a better workout.

And all this is magnified when you move from minimalist shoes to a true barefoot experience.

When your sole touches the ground, you enjoy all kinds of sensations. Hot, cold, wet, dry. Remember squishing in the mud when you were a kid, or burrowing into cool sand? It’s fun to feel with your feet!

Should anyone avoid minimalist footwear or barefoot running?

Most kinds of feet can do well in minimalist shoes. But there are a few exceptions.

Let’s take a closer look.

Flat feet

If your feet are flat, you might worry that you require arch support.

But try spending a little bit of time each day walking or running barefoot or in flexible footwear. Your feet will get stronger and you may feel differently.

Orthotics

Maybe you wear orthotics. Does that mean you can’t go minimalist?

It depends.

If you’re wearing orthotics because of metatarsal or footpad disease, you should probably stick to shoes that make room for the device. You’d have significant pain without the extra protection.

But if orthotics are simply a “site of pain” solution for a nonspecific injury, by practicing more dynamic joint mobility and exploring more flexible footwear in a gradual, progressive way, you may improve your posture and gait as well as your mobility. You might even free yourself of the orthotics.

Foot deformities and numbness

Those with foot differences that affect gait (e.g. clubfoot) should take extra care. But they may be able to run in minimalist or barefoot shoes, with proper coaching. (I have worked with runners in this situation.)

Barefoot running may actually improve bunions. It sounds counter-intuitive, since the forefoot strikes the ground with greater force, but many runners attest to the effect.

The only people who really shouldn’t try minimalist shoes or barefoot running are those with diseases (like diabetes) that cause numbness in the feet.

Only for running?

What if you’re not into running? Are there other places to wear minimalist shoes?

You bet.

Walking and hiking in minimalist footwear is a great experience. You really feel the ground under your feet. People who do it say it’s like being a kid again.

Also, there’s an old school approach to power lifting that prefers Converse Chuck Taylors to any other kind of shoe, precisely because they allow the wearer to feel the ground. And many home gym users prefer to be barefoot.

What about other sports?

As great as minimalist footwear is, it’s not for every activity. Even the most ardent barefoot and minimalist types will lace up for certain kinds of sports.

Dr. Mick Wilkinson, who is barefoot in the UK north twelve months a year, wears shoes for racquetball. Stephen Sashen, the guy who has modernized the huarache with Xero Shoes, wears spikes for sprinting.

It would be challenging to strike a football without some toe cover. Power to the pedal in cycling owes a lot to stiff soles.

There’s also an entire wonderful history about lifting shoes and how they have gone from almost a boxer type lace up to stiff, wooden soled versions with some heel lift intended to reduce the strain on the Achilles tendon.

How to find a minimalist shoe

Let’s say you’re intrigued by the research and ready to give minimalist footwear a try. How will you recognize a minimalist shoe?

First, they come in a couple of different varieties, from the separated toe versions to footwear that looks more like a traditional shoe.

But all minimalist shoes share the following characteristics:

- The cushioning in the front and back of the shoe is about the same, and not very thick.

- The sole will be flexible. You’ll easily be able to bend it at the midfoot. But that’s not all. It will also be twistable along the length of the long axis. In fact, if you can’t twist it as if you were ringing out a towel, it’s probably not minimalist.

- There won’t be a stiff arch support.

Transitioning to minimalist footwear and barefoot running

If you’re ready to try minimalist footwear or barefoot running, transition gradually.

(I can’t emphasize that enough so I’ll say it again: Transition gradually).

For example, first increase the flexibility of your shoe, and only afterwards consider reducing its “squishiness.” Look at this as an experiment where you change only one variable at a time.

- Start indoors:

Let your foot get used to this less structured shoe by wearing it indoors during the day, in the office, up and down stairs. - After several days, go outside.

Next, take yourself outdoors in the shoe for 15 minutes. See how you feel walking over different surfaces. Your feet may get tired at first. Stop before they get really sore. - Think of this as progressive resistance.

If your feet don’t hurt after 15 minutes the first day, great! Stop anyway. Try 20 minutes the next day. - Keep building up slowly.

Once you’ve built up to an hour outside and you feel good, you may be ready to explore further and longer. Feel free to bring along some “back up” familiar shoes to swap into. - Have a backup plan once you decide to increase your duration or intensity.

Alternatively, have an exit plan like a bus stop or cab to get you back to square one. This will reduce any stress you might feel if your feet do get sore. - Work on your gait before going all out.

If you plan to run, you can begin to prepare your calves and hips for the new motion by practicing a more mid or forefoot gait. See how that feels. You might find a coach to help you. - Think about stride length and frequency once you start running.

Count your turn over. Try to get your cadence with a mid or forefoot strike in the 180 zone. - Pay attention.

See how you calves feel doing this in your regular shoes before you try something like the frees. - Slowly build up your new technique in the new shoes.

Once that adaptation’s working for you, try 15 minutes on a few different surfaces in your minimal shoes. - Build up gradually.

Again, if I don’t say this a million times you’ll ignore it. So build up slowly. Unless you like injury and pain. If so, by all means, buy a pair of minimalist shoes and go for a 5K run during the first week.

Again, when you feel happy with your increased mobility and you’ve explored your forefoot gait and those muscle adjustments in your running, you can start to reduce the “squish” in your shoes.

Start indoors at a good temperature. Most minimalist footwear is 4-7 mm deep. That can be a very big change from the Free or any other twisty shoe.

When you first head outside, be prepared to be very aware of the surfaces beneath your feet. Again, take it easy and go short at first.

Personally, I suggest folks do a lot of indoor walking in thin-soled shoes like Vibram Five Fingers or Merell Trail Gloves before heading outdoors. And once again, if you decide to go even further and try barefoot running, you’ll need to go through a similar process.

It’s an adventure. Surfaces that you never felt before can now offer massages to your feet.

Joint mobility matters

Another complementary approach to prepare you for minimalist footwear is to practice dynamic joint mobility.

Movement in walking and running doesn’t only happen at the foot. Minimalist footwear cues us to more use of our joints.

By working on our dynamic joint mobility — deliberately firing up our nervous system’s awareness around our joints— we become more responsive and more prepared for the new demands.

Above all: Listen to your body

Full disclosure: my footwear has been “passing the twist test” since 2008 when I started wearing Vibram Five Fingers. Since then my flexible footwear has included a wide variety of twist test passing shoes. (Though I haven’t gone as far as chain mail.

If you choose to make the change, just remember: tissue building takes time. Months of time.

But if you let yourself build up gradually to minimalist footwear, you may never turn back.

Eat, move, and live… better.©

Yep, we know… the health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. Even when it comes to something as simple as shoes. But it doesn’t have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies — unique and personal — for you.

Click here to download the special report, for free.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Share